Diary of a Rambling Antiquarian

Wednesday, 26 January 2005

Quanzhou Museum of Maritime History

I'm visiting China for a week. This is my first time here since 1992, when I spent spent several months hunting for rare editions of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms in libraries in England, Spain, China and Japan as research for my PhD dissertation. A lot has happened (and not happened) since then, and my research interests have now shifted away from literature, and towards obscure historical writing systems used in East Asia. Two years ago I submitted a proposal to encode the Phags-pa script in Unicode, and I have been invited to attend a meeting in Xiamen 厦門 of the WG2 working group of the ISO committee responsible for maintaining the ISO/IEC 10646 standard (the international standard corresponding to, and synchronized with, the Unicode standard). This meeting will be key to getting an agreement between the various interested parties (myself, experts from China and Mongolia, and representatives of the Unicode Consortium and various national bodies) on the encoding model for Phags-pa. Success will allow the encoding of Phags-pa to progress, but failure will mean that the encoding of Phags-pa may be delayed indefinitely.

I arrived in Guangzhou on Sunday, and flew to Xiamen on Monday morning. This is my first time in Fujian province, which is ironic given that the great majority of early editions of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms that I studied all those years ago were published during the Ming dynasty by the numerous commercial publishing houses based in Jianyang County of Fujian (almost all of the surviving examples of these popular commercial editions of the Three Kingdoms were taken to Japan or Europe as souvenirs, and the earliest extant edition entered the collection of the Royal Library at the Escorial Monastery during the 16th century).

Yesterday we had a long ad hoc meeting on Phags-pa, which resulted in agreement on progressing the encoding of Phags-pa using the model that I had proposed. So after yesterday's success I have decided to take today off, and go in search of some real live Phags-pa inscriptions. There are relatively few surviving examples of monumental inscriptions in the Phags-pa script, so I am very lucky that the WG2 meeting is being held in Xiamen, as Quanzhou 泉州, about 70 km up the coast, is home to some very unusual examples of the Phags-pa script.

There is no railway line between Xiamen and Quanzhou, so I have to take a bus. I leave the hotel early and get to the bus station in time to catch the 8:00 bus, and after a slow and sometimes bumpy drive, we arrive in Quanzhou a little before midday. Quanzhou was known to Marco Polo as Zayton, and during the Yuan dynasty it was the greatest port of the Mongolian empire.

Of the City and Great Haven of Zayton

Now when you quit Fuju [Fuzhou] and cross the River, you travel for five days south-east through a fine country, meeting with a constant succession of flourishing cities, towns, and villages, rich in every product. You travel by mountains and valleys and plains, and in some places by great forests in which are many of the trees which give Camphor. There is plenty of game on the road, both of bird and beast. The people are all traders and craftsmen, subjects of the Great Kaan, and under the government of Fuju. When you have accomplished those five days' journey you arrive at the very great and noble city of ZAYTON, which is also subject to Fuju.

At this city you must know is the Haven of Zayton, frequented by all the ships of India, which bring thither spicery and all other kinds of costly wares. It is the port also that is frequented by all the merchants of Manzi [southern China], for hither is imported the most astonishing quantity of goods and of precious stones and pearls, and from this they are distributed all over Manzi. And I assure you that for one shipload of pepper that goes to Alexandria or elsewhere, destined for Christendom, there come a hundred such, aye and more too, to this haven of Zayton; for it is one of the two greatest havens in the world for commerce.

Henry Yule and Henri Cordier (eds.), The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East (London: John Murray, 1903) vol. II (Book II Chapter LXXXII).

Quanzhou is now miles from the sea, but it is home to the Quanzhou Museum of Maritime History (海外交通史博物館). The museum has a marvellous collection of stone monuments dating from the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), with inscriptions in a wide range of scripts and languages, reflecting the cosmopolitan nature of the city during the 13th and 14th centuries. In addition to a large collection of Islamic tombstones, the museum houses carvings from a Hindu temple dedicated to Śiva that was built by Tamil inhabitants of the city, as well as monuments representing Manichaeism and Christianity.

Carving of Śiva from a Hindu temple in Quanzhou

During the Yuan dynasty the Catholic church first established a presence in China. A series of Franciscan missions had been sent out by the papacy to Persia, India and China from the year 1241, but the first mission to actually reach China was that of John of Montecorvino (1246–1328), who in 1294 arrived at the capital of the Mongol Empire, Cambaluc (literally "City of the Khan", which is modern Beijing). He built two churches in the capital, and is reputed to have translated the New Testament and Psalms into Chinese, but these translations no longer exist. In 1307 Pope Clement V sent seven Franciscan friars, each with the rank of bishop, to China in order to consecrate John as Archbishop of China. Only three of the seven, Gerard, Peregrine (Peregrinus de Castello) and Andrew of Perugia, survived the long journey, arriving in Cambaluc in 1308.

John sent Friars Gerard and Peregrine to Zayton to establish the first Catholic mission in China outside of the capital. It seems that Zayton was chosen as it already had a Christian presence there in the form of a church that had been founded by a "rich Armenian lady". This church was established as a cathedral, and Gerard became the first bishop of Zayton. The fact that the existing church was converted into the Catholic cathedral would suggest that it may have been a Catholic church, and that at least some of the existing Christians of Zayton may have been Catholics associated with maritime trade rather than all Nestorians from Central Asia, who the Franciscans regarded as heretics.

After Gerard's death in 1313, Friar Peregrine was installed as the second bishop of Zayton. In 1318, Friar Andrew, who had remained at the capital, was also dispatched to Zayton, and he organized the construction of a new church outside the city. Four years later, in 1322, when Bishop Peregrine died, Andrew became the third bishop of Zayton. In a letter to Rome dated 1326, Andrew tells us all about his mission to Zayton :

Friar Andrew of Perugia, of the Order of Minor Friars, by Divine permission called to be Bishop, to the reverend father the Friar Warden of the Convent of Perugia, health and peace in the Lord for ever !

.... On account of the immense distance by land and sea interposed between us, I can scarcely hope that a letter from me to you can come to hand. .... You have heard then how along with Friar Peregrine, my brother bishop of blessed memory, and the sole companion of my pilgrimage, through much fatigue and sickness and want, through sundry grievous sufferings and perils by land and sea, plundered even of our habits and tunics, we got at last by God's grace to the city of Cambaliech [modern Beijing], which is the seat of the Emperor the Great Chan, in the year of our Lord's incarnation 1308, as well as I can reckon.

There, after the Archbishop [John of Montecorvino] was consecrated, according to the orders given us by the Apostolic See [Pope Clement V], we continued to abide for nearly five years ; during which time we obtained an Alafa from the emperor for our food and clothing. An alafa is an allowance for expenses which the emperor grants to the envoys of princes, to orators, warriors, different kinds of artists, jongleurs, paupers, and all sorts of people of all sorts of conditions. And the sum total of these allowances surpasses the revenue and expenditure of several of the kings of the Latin countries.

As to the wealth, splendour, and glory of this great emperor, the vastness of his dominion, the multitudes of people subject to him, the number and greatness of his cities, and the constitution of the empire, within which no man dares to draw a sword against his neighbour, I will say nothing, because it would be a long matter to write, and would seem incredible to those who heard it. Even I who am here in the country do hear things averred of it that I can scarcely believe. ...

There is a great city on the shores of the Ocean Sea, which is called in the Persian tongue Zayton [properly known as Quanzhou in Chinese]; and in this city a rich Armenian lady did build a large and fine enough church, which was erected into a cathedral by the Archbishop himself of his own free-will. The lady assigned it, with a competent endowment which she provided during her life and secured by will at her death, to Friar Gerard the Bishop, and the friars who were with him, and he became accordingly the first occupant of the cathedral.

After he was dead however and buried therein, the Archbishop wished to make me his successor in the church. But as I did not consent to accept the position he bestowed it upon Friar and Bishop Peregrine before mentioned. The latter, as soon as he found an opportunity, proceeded thither, and after he had governed the church for a few years, in the year of the Lord 1322, the day after the octave of St. Peter and St. Paul, he breathed his last.

Nearly four years before his decease, finding myself for certain reasons uncomfortable at Cambaliech, I obtained permission that the before mentioned alafa or imperial charity should be allowed me at the said city of Zayton, which is about three weeks journey distant from Cambaliech. This concession I obtained as I have said, at my earnest request, and setting out with eight horsemen allowed me by the emperor, I proceeded on my journey, being everywhere received with great honour. On my arrival (the aforesaid Friar Peregrine being still alive) I caused a convenient and handsome church to be built in a certain grove, quarter of a mile outside the city, with all the offices sufficient for twenty-two friars, and with four apartments such that any one of them is good enough for a church dignitary of any rank. In this place I continue to dwell, living upon the imperial dole before-mentioned, the value of which, according to the estimate of the Genoese merchants, amounts in the year to 100 golden florins or thereabouts. Of this allowance I have spent the greatest part in the construction of the church ; and I know none among all the convents of our province to be compared to it in elegance and all other amenities.

And so not long after the death of Friar Peregrine I received a decree from the archbishop appointing me to the aforesaid cathedral church, and to this appointment I now assented for good reasons. So I abide now sometimes in the house or church in the city, and sometimes in my convent outside, as it suits me. And my health is good, and as far as one can look forward at my time of life, I may yet labour in this field for some years to come : but my hair is grey, which is owing to constitutional infirmities as well as to age.

'Tis a fact that in this vast empire there are people of every nation under heaven, and of every sect, and all and sundry are allowed to live freely according to their creed. For they hold this opinion, or rather this erroneous view, that everyone can find salvation in his own religion. Howbeit we are at liberty to preach without let or hindrance. Of the Jews and Saracens there are indeed no converts, but many of the idolaters are baptised ; though in sooth many of the baptised walk not rightly in the path of Christianity.

Four of our brethren have suffered martyrdom in India, at the hands of the Saracens ; and one of them was twice cast into a great blazing fire, but came out unhurt. And yet in spite of so stupendous a miracle not one of the Saracens was converted from his misbelief !

All these things I have briefly jotted down for your information, reverend father, and that through you they may be communicated to others. I do not write to my spiritual brethren or private friends, because I know not which of them are alive, and which departed, so I beg them to have me excused. But I send my salutation to all, and desire to be remembered to all as cordially as possible, and I pray you, father Warden, to commend me to the Minister and Custos of Perugia, and to all the other brethren. All the suffragan bishops appointed to Cambaliech and elsewhere by our lord Pope Clement have departed in peace to the Lord, and I alone remain. Friar Nicholas of Banthera, Friar Andrutius of Assisi, and another bishop [Ulrich Sayfusstorf], died on their first arrival in Lower India, in a most cruelly fatal country, where many others also have died and been buried.

Farewell in the Lord, father, now and ever. Dated at Zayton, A.D. 1326, in the month of January.

Henry Yule (trans. and ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither; being a collection of Medieval Notices of China (London: The Hakluyt Society, MDCCCLXVI) vol.1 pp. 496–499.

It was whilst Andrew was bishop that Friar Odoric visited China, in his account of which he has this to say about Zayton :

30. Concerning the noble city called Zayton ; and how the folk thereof regale their gods.

Departing from that district, and passing through many cities and towns, I came to a certain noble city which is called Zayton, where we friars minor have two houses ; and there I deposited the bones of our friars who suffered martyrdom for the faith of Jesus Christ.

In this city is great plenty of all things that are needful for human subsistence. For example you can get three pounds and eight ounces of sugar for less than half a groat. The city is twice as great as Bologna, and in it are many monasteries of devotees, idol worshippers every man of them. In one of those monasteries which I visited there were three thousand monks and eleven thousand idols. And one of those idols, which seemed to be smaller than the rest was as big as St. Christopher might be. I went thither at the hour fixed for feeding their idols, that I might witness it ; and the fashion thereof is this : All the dishes which they offer to be eaten are piping hot so that the smoke riseth up in the face of the idols, and this they consider to be the idols' refection. But all else they keep for themselves and gobble up. And after such fashion as this they reckon that they feed their gods well.

The place is one of the best in the world, and that as regards its provision for the body of man. Many other things indeed might be related of this place, but I will not write more about them at present.

Henry Yule (trans. and ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither; being a collection of Medieval Notices of China (London: The Hakluyt Society, MDCCCLXVI) vol. I pp. 381–383.

Andrew remained Bishop of Zayton until his death in 1332. In 1946 a tombstone with a Latin inscription was discovered in Quanzhou, and this has been identified as that of Andrew or Perugia.

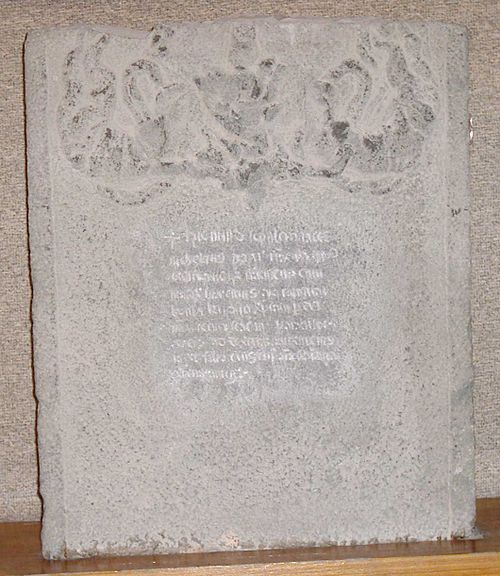

Supposed Tombstone of Andrew of Perugia

(Copy of the stone on display at the Quanzhou Museum of Maritime History; the original is in Beijing)

Unfortunately the Latin inscription is badly worn and can only be partially read. The accepted reading of the inscription, made by Professor C. J. Fordyce in John Foster's "Crosses from the walls of Zaitun" (Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (N.S.) 1954 pp. 1–25), is :

☩ Hic (in PFS) sepultus est

Andreas Perusinus (de-

votus ep. Cayton .......

.......ordinis (fratrum

min.) ..................

... (Jesus Christi) Apostolus

............................

........(in mense) .......

m(cccxx)xii ☩

But this reading does not seem to correspond well with what I can make out of the inscription, and beyond the first word (hic) I find it difficult to match Fordyce's reading to the actual inscription. In particular I do not see the words "Andreas Perusinus", so I have severe doubts about the validity of the accepted reading or whether it is indeed a memorial to Bishop Andrew. My doubts are shared by eminent Sinologist Herbert Franke, who states of this stone :

It must be Christian because the inscription begins

with the sign of the Cross, but the attempt to read it as Latin and

to regard it as the tomb inscription for Andrew of Perugia, the

third suffragan bishop of Zayton — modern Ch'uan-chou — does

not seem convincing. The only thing that can be said with certainty

is that the inscription is not in Syriac script.Herbert Franke, "Sino-Western Contacts under the Mongol Empire"; Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society vol. 6 (1966) 49–72.

After Andrew's death in 1332 a Paris theologian called Nicholas, who had arrived in China with twenty-six friars and six lay brothers, succeeded to the bishopric, but there are no detailed accounts of the later years of the Zayton mission. Nevertheless, the church in Zayton was evidentally still going strong when John Marignolli visited the city in about 1347 :

There is Zayton also, a wondrous fine seaport and a city of incredible size, where our Minor Friars have three very fine churches, passing rich and elegant ; and they have a bath also and a fondaco [a factory, i.e. "a mercantile establishment and lodging house in a foreign country"] which serves as a depôt for all the merchants. They have also some fine bells of the best quality, two of which were made to my order, and set up with all due form in the very middle of the Saracen community. One of these we ordered to be called Johannina, and the other Antonina.

Henry Yule (trans. and ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither; being a collection of Medieval Notices of China (London: The Hakluyt Society, MDCCCLXVI) vol. II pp. 115–116.

One of the last bishops of Zayton may have been a certain Friar James of Florence, who was martyred in the "Empire of the Medes" (i.e. the Empire of Chaghatai) in 1362, and is recorded to have been "Archbishop of Zaiton". After the fall of the Mongol empire in 1368, the Catholic missions in China disappeared, and there was no further Catholic presence in China until the Dominican friar Gaspar da Cruz arrived in China in 1555.

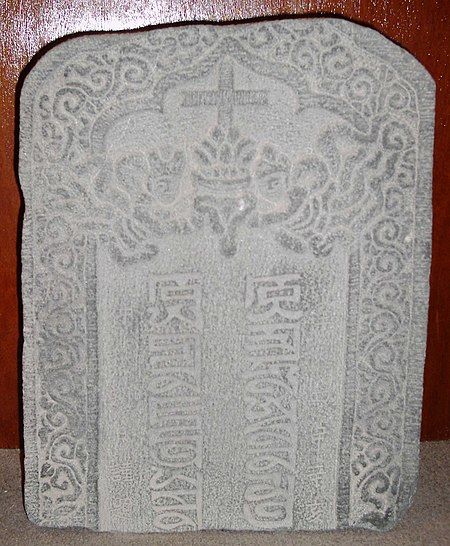

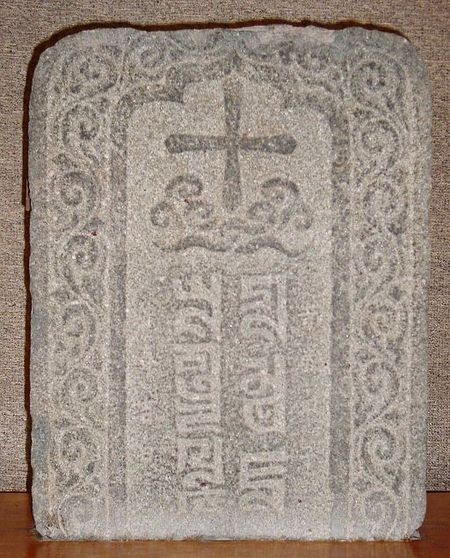

In addition to the supposed tombstone of Bishop Andrew, up to forty other Yuan dynasty Christian tombstones have been unearthed in Quanzhou. Most of the inscribed Christian tombstones from Quanzhou have inscriptions written in the Uyghur language using the Syriac script, and are no doubt memorials to members of the Assyrian ("Nestorian") church who originally came from the western parts of the Mongol empire (many similar tombstones with Syriac inscriptions have also been found in the west of China and elsewhere in central Asia, especially Kyrgyzstan). However, there are four Christian tombstones that have their main inscription written in Chinese using the Phags-pa script, and it these four highly unusual stones that I have specially come to see today.

Tombstone of Zhu Yanke (1311)

ꡁꡗ ꡚꡋ ꡆꡦꡟ ꡗꡠꡋ ꡁꡡ ꡒꡜꡞ ꡝꡧꡞꡋ ꡏꡟ

khay shan jėu yen kho dzhi 'win mu

開山朱延可子雲墓

Tomb of Zhu Yanke [styled] Ziyun of Kaishan

至大四年辛亥,仲秋朔日謹題

In the cyclical year xinhai [year of the golden pig] in the fourth year of the Zhida period [1311],

respectfully inscribed on the first day of the second autumn month

Tombstone of Yang Wengshe (1314)

ꡖꡟꡃ ꡚꡦ ꡗꡃ ꡚꡞ ꡏꡟ ꡈꡓ

·ung shė yang shi mu taw

翁舍楊氏墓道

Tomb memorial of Yang Wengshe

延祐甲寅,良月吉日

In the cyclical year jiayin [year of the wooden tiger] of the Yanyou period [1314],

on a good month and an auspicious day

Tombstone of Liu Yigong (1324)

ꡗꡞ ꡂꡟꡃ ꡙꡞꡓ ꡚꡞ ꡏꡟ ꡆꡞ

yi gung liw shi mu ji

易公(劉/柳)氏墓誌

Tomb memorial of Liu Yigong

旹歲甲子,仲春吉日

In the cyclical year jiazi [year of the wooden rat = Taiding 1 (1324)], on an auspicious day of the second spring month

Tombstone of Madam Ye (undated)

ꡗꡠ ꡚꡞ ꡏꡟ ꡆꡞ

ye shi mu ji

葉氏墓誌

Tomb memorial of Madam Ye

These four stones are dated 1311, 1314 and 1324, which makes them exactly contemporary with the mission in Zayton of Bishops Gerard, Peregrine and Andrew (1308–1332), and I think that it is possible that these four stones may be associated with the Franciscan bishopric of Zayton rather than the Assyrian church. There are two significant differences between the Phags-pa/Chinese tombstones and the Syriac/Uyghur tombstones. Firstly, whereas the Syriac tombstones are for people with Turkic names, the Phags-pa tombstones are for people with Chinese names. Secondly, whereas the Syriac tombstones usually have an overtly Christian inscription, such as the words "In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit ...", the Phags-pa tombstones only give the name of the deceased and the date of their death, but do not have any Christian text. I think that the four Phags-pa tombstones may have been for Chinese converts to the church at Zayton established by Bishop Gerard, and that they use the phonetic Phags-pa script rather than Chinese characters as it was much easier for the Franciscan missionaries to learn forty-one Phags-pa letters than thousands of Chinese characters.

Fujan | Museums | Phags-pa | Yuan dynasty

Index of Rambling Antiquarian Blog Posts

Rambling Antiquarian on Google Maps