Diary of a Rambling Antiquarian

Wednesday, 3 August 2011

Cloud Platform at Juyongguan

After spending yesterday morning with the whole family at the Badaling section of the Great Wall of China, and the afternoon by myself investigating the National Museum of China [gallery of my photos], today I want to go out and explore somewhere of special antiquarian interest. There are so many places that I should have visited when I was a student in Beijing in the mid 1980s, but which I never did, either through ignorance or through circumstances (mostly the former). Twenty-five years later, the place in Beijing that I most want to visit is somewhere that I had not even heard of back then. It was only in 1987, after I had returned to my studies at SOAS in London that one day in the library I happened upon a huge two-volume book published in Japan in 1957, entitled in English, Chü-Yung-Kuan: The Buddhist Arch of the Fourteenth Century A.D. at the Pass of the Great Wall Northwest of Peking. Idly flicking through the pages of that great tome, I was confounded by inscriptions in unknown languages and strange scripts which I had never imagined could adorn a monument so close to Beijing and yet now so far away. The book was a revelation to me, and for the first time my eyes were opened to the multiplicity of language and script in medieval China. However, at that time my sinological studies were moving in a different direction, and I little thought that twenty years thence my life would become so intertwined with the Phags-pa, Tangut, Khitan and Jurchen scripts and languages.

My two children want to see pandas, so my wife is taking them to Beijing Zoo for the day. I rise early (well, earlyish) and search the internet for clues on how to get to the Great Wall at Juyongguan (居庸關), about 60 kilometres northwest of central Beijing, where the edifice is located. The railway line runs past the Juyong Pass but to my dismay I discover that the Juyongguan Railway Station has been closed to passenger trains since last year, and that the recommended routes are tourist bus or taxi, neither of which suits me. I eventually discover that rural bus #68 from Dragon's Marsh should go there, so out of the hotel and onto the underground I go. Outside the underground station in North Beijing there are lots of buses, but no stop for #68. I am about to give up and go to the zoo when the #68 pulls up, so I jump on board, to the evident bemusement of the bus conductor who rarely carries foreign passengers. The ticket is only ¥10 for the 34 stops of the journey, winding idiosyncratically through the north Beijing suburbs and on through the towns and villages of Changping District, apparently always following the smallest and bumpiest roads. After nearly two hours the bus pulls into an empty carpark at a far, desolate corner of Juyong Pass. I was the only passenger to get on at the start, and although other passengers came and went, I was the only one get off at the terminus.

To my amazement, the Cloud Platform was right there in the middle of the car park, half a stone's throw from where the bus stopped. I bought the obligatory souvenir entrance ticket (for all of the Juyong Pass tourist area, although I only want to see the Cloud Platform, having had enough of walls yesterday), and in I go. All the tourists are busy clambering the wall in the distance, so I have the monument entirely to myself.

Entrance ticket for Great Wall at Juyong Pass

View of the Cloud Platform from the North (in the Car Park)

Constructed between 1342 and 1345 by imperial command, the Cloud Platform (雲臺) is a marble-clad platform built to support three white dagobas (stupa-shaped pagodas), with a passageway running through it from south to north. It was positioned on the main road running northwards from the Yuan dynasty capital of Dadu (modern Beijing), and the emperor would pass under the three dagobas on his way to and from the summer capital of Shangdu (Xanadu). The dagobas have long since collapsed, and today it looks like a monumental arch. The reason that the platform is of such particular interest to me is that the inside walls of the passageway are engraved with Buddhist texts in six different scripts: Lanydza (Sanskrit), Tibetan, Old Uyghur, Phags-pa, Tangut, and Chinese. Having been responsible for the encoding of the Phags-pa script in Unicode, and having being deeply involved in continuing attempts to encode the Tangut script over the last few years, I am naturally keen to see actual examples of these two scripts in the wild. I managed to see some Yuan dynasty Christian gravestones with Phags-pa inscriptions when I was last in China in 2005, but I have never seen any Tangut inscriptions in the wild, and indeed yesterday at the National Museum of China may have been the first time I have even seen a Tangut-inscribed artefact in person.

View of the Cloud Platform from the South

Cloud Terrace

Built in the 2nd year of the reign of Emperor Zhizheng of the Yuan Dynasty (1342 A.D.), this terrace used to be the base of a crossing-street pagoda (a pagoda with a passageway for traffic). At the turn of the Yuan and the Ming dynasties, the three lama pagodas over it were destroyed one after another. In the early Ming Dynasty a Buddhist hall was built on it. Observing from afar the magnificent hall seemed to rise into the clouds. For this reason, it was called the ‘Stone Pavilion in the Clouds’ in the Ming Dynasty. In the 5th lunar month of the 41st year of the reign of Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty (1702 A.D.), the Buddhist hall was destroyed in a fire. Its foundation, the Cloud Terrace as was known, however, was kept till today. The Shifang Buddha (the Buddha of All Sides), Four Deva-kings, and Mandala in the arched caves and rocs, whales, dragons and other Buddhist patterns on its four sides are carved with exquisite skills. Between the Buddhist statues are carved the Dharani Sutra in Sanskrit, Tibetan, Phags-pa, Uyghur, Xixian, and Chinese languages and the Record of Merits in the Construction of the Pagoda in Tibetan, Phags-pa, Uyghur, Xixia and Chinese languages. It provides a rare evidence for the study of ethnic cultures.

—from the information board

[You can read more about the Cloud Platform from this Wikipedia article about it that I wrote as one of my contributions to the International Dunhuang Project Wikipedia editathon in October 2012.]

The plaform is renowned for its bas-relief carvings of Buddhist images in the Tibetan style. On the semi-octagonal arches at both ends of the passageway there are identical carvings of a youth riding a mythical creature on top of an elephant on top of a crossed vajra on either side of the entrance, and a garuda catching a pair of half-human, half-snake nagaraja above the entrance.

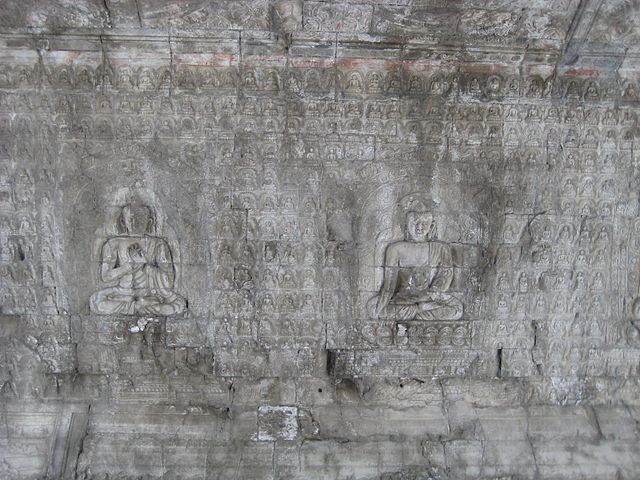

Close up of the South Arch

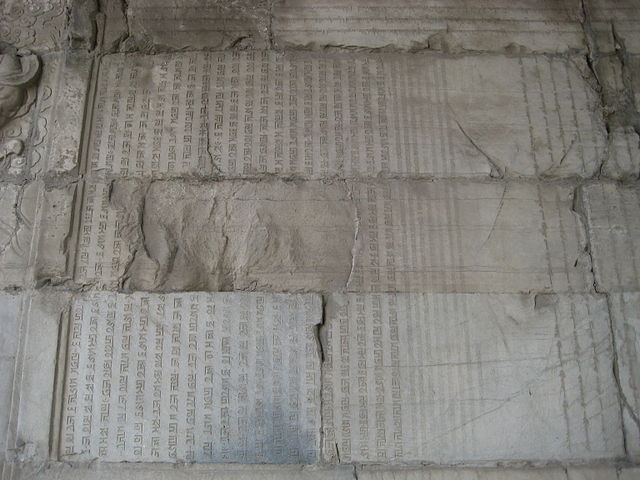

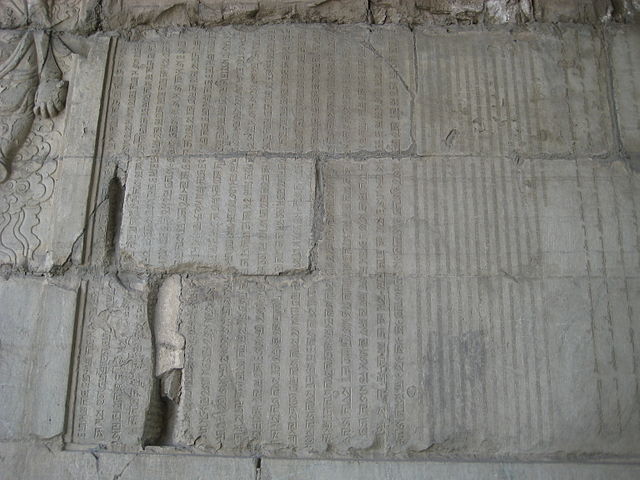

Every inch of the interior walls and ceiling of the passageway are decorated with Buddhist carvings or inscriptions. The ends of both interior walls of the passageway are protected by carvings of the Four Deva Kings. On each wall between the Deva kings, Buddhist texts are engraved in six different scripts. On each sloping ceiling are five of the Buddhas of the Ten Directions, embedded within small images of the Thousand Buddhas of the present kalpa. The passageway is topped with the mandalas of the Five Dhyani Buddhas.

On each wall a Sanskrit dharani is engraved in large characters in six different scripts:

- Lanydza script

- Tibetan script

- Phags-pa script

- Old Uyghur script

- Chinese script

- Tangut script

On the east wall is engraved the Dharani of the Victorious Buddha-Crown (Sanskrit Uṣṇīṣa-vijaya-dhāraṇī, Chinese Fódǐng Zūnshèng Tuóluóní 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼), whereas on the west wall is engraved the Dharani of the Tathagata Heart (Sanskrit Tathāgata-hṛdaya-dhāraṇī, Chinese Rúláixīn Tuóluóní 如來心陀羅尼). In addition to the two dharanis, a "Record of Merits in the Construction of the Pagoda" is engraved in small characters in five languages and scripts:

- Tibetan language and script

- Mongolian language and Phags-pa script

- Old Uyghur language and script

- Chinese language and script

- Tangut language and script

The Tibetan, Mongolian and Old Uyghur versions of the "Record of Merits" are written over both the east and west walls, whereas the Chinese and Tangut versions are complete on the east wall, and the small script Chinese and Tangut inscriptions on the west wall are summaries of the "Dharani of the Tathagata Heart". At the end of the Chinese version of the summary of the "Dharani of the Tathagata Heart" is an inscription specifying that it was written on an auspicious day of the 9th month of the 5th year of the Zhizheng era (1345) by a monk called Decheng (德成) from the Baoji Temple (寶積寺) in Chengdu.

Layout of the East Wall

Dharani of the Victorious Buddha-Crown

| Five Mandalas (on the ceiling between east and west walls) |

|||||||||||

Five Buddhas of the Ten Directions (on the sloping ceiling) |

|||||||||||

| Deva King of the South |

Lanydza Script (horizontal, left-to-right) | Deva King of the East |

|||||||||

| Tibetan Script (horizontal, left-to-right) | |||||||||||

Phags-pa Script (vertical left-to-right) |

Old Uyghur Script (vertical left-to-right) |

Tangut Script (vertical right-to-left) |

Chinese Script (vertical right-to-left) |

||||||||

Layout of the West Wall

Dharani of the Tathagata Heart

| Five Mandalas (on the ceiling between west and east walls) |

|||||||||||

Five Buddhas of the Ten Directions (on the sloping ceiling) |

|||||||||||

| Deva King of the North |

Lanydza Script (horizontal, left-to-right) | Deva King of the West |

|||||||||

| Tibetan Script (horizontal, left-to-right) | |||||||||||

Phags-pa Script (vertical left-to-right) |

Old Uyghur Script (vertical left-to-right) |

Tangut Script (vertical right-to-left) |

Chinese Script (vertical right-to-left) |

||||||||

The layout of the six scripts on the Cloud Platform is mirrored by the layout of the same six scripts used to engrave the Buddhist mantra Om mani padme hum on the 1348 Stele of Sulaiman at Dunhuang, the only difference being that the positions of Phags-pa and Old Uyghur are swapped on the 1348 stele.

Deva King of the East

Deva King of the South

Deva King of the West

Deva King of the North

Multiscript Buddhist inscriptions on the east wall

Multiscript Buddhist inscriptions on the west wall

Sanskrit (Lantsa) and Tibetan inscriptions on the east wall

Phags-pa inscription on the east wall

Phags-pa inscription on the west wall

Old Uyghur inscription on the east wall

Old Uyghur inscription on the west wall

Tangut inscription on the east wall

Tangut inscription on the west wall

Chinese inscription on the east wall

Chinese inscription on the west wall

Buddhas of the Ten Directions on the east ceiling (1)

Buddhas of the Ten Directions on the east ceiling (2)

Buddhas of the Ten Directions on the east ceiling (3)

Buddhas of the Ten Directions on the west ceiling (1)

Buddhas of the Ten Directions on the west ceiling (2)

Buddhas of the Ten Directions on the west ceiling (3)

Half an hour later, and 107 photos taken (one short ... aaagh), I was back on the rambling bus route to Beijing city, serenely happy to have seen and touched Tangut text in the wild for the first time in my life. It is only after I get back to the hotel room and am reviewing the pictures that I realise that I took photos of every inch of the decorated or inscribed parts of the monument, except for the five mandalas running along the centre of the ceiling of the arch, which being immediately above my head as I was taking the pictures escaped my attention.

Postscript (December 2013)

I returned to Beijing for a conference on Tangut encoding in December 2013, and our organized excursion was to the Cloud Platform and the Great Wall. However, it was only a short stopover at the Cloud Platform, and so I only had time for a few photographs before being dragged back to the coach.

In front of the Cloud Platform in December 2013

In front of the Tangut inscription on the east wall of the arch

(Here is my photograph of Michael Everson looking very Matrix.)

To complete this post, here is a photo I took of one of the five mandalas running along the centre of the ceiling of the arch.

Middle of five mandalas carved along the central ceiling

Beijing | Pagodas | Phags-pa | Tangut | Yuan dynasty

Index of Rambling Antiquarian Blog Posts

Rambling Antiquarian on Google Maps