Diary of a Rambling Antiquarian

Thursday, 25 August 2016

Kharakhoto

Yesterday afternoon we arrived in Dalaihob, the seat of Ejina Banner in the far west of Inner Mongolia, after a two-day journey from Yinchuan, and today is the day that we will visit the famed ruins of the abandoned fortress city of Kharakhoto (Mongolian for Black City), known in Chinese as Black City (Hēichéng 黑城) or Black Water City (Hēishuǐchéng 黑水城).

During the rule of the Western Xia, Kharkhoto was a frontier garrison on the edge of the Gobi desert. Then in 1227 the Mongols overthrew the Western Xia kingdom, and Kharakhoto in turn came under the control of the Mongol Empire and later the Yuan dynasty. Finally, in 1372 the city was besieged by the army of the Ming dynasty, who (legend says) diverted the course of the Black Water river, dooming the city and its inhabitants. Lost in the shifting sands for hundreds of years, Kharakhoto was only rediscovered by foreigners in 1908 when a Russian explorer called Pyotr Kozlov found his way there, and subsequently discovered thousands of books written in the Tangut language inside a Buddhist stupa standing outside the walls of the city (see Prof. Kychanov's Preface to Documents from the Black River City held in Russia for details).

We had arranged to hire a taxi for the day, and it arrived at our hotel early in the morning. We travel 20 km south of Dalaihob on the main road, and shortly after crossing the Black Water river we turn off the highway, onto a small road heading east towards Kharakhoto. The Black Water was a mighty torrent of water, wide and deep, and not at all the trickle of water through the desert that I had expected, but unfortunately I missed the opportunity ask our driver to stop so that I could take a photograph.

A short way down the small road we reach the entrance to the tourist area that encompasses Kharakhoto and other historical sites. It is here that we buy our entrance tickets, which I have to admit are not terribly impressive.

Entrance ticket for the Ejina Heishuicheng Tourist Area

From here it is a drive of about 15 km until we reach our destination. We park in the almost empty reception area about 500 metres west of the walls of Kharakhoto (a little south of the spot marked "II" in Stein's plan below). During our time at the site there were only a handful of other visitors, a couple of people who were leaving as we arrived and one other visitor who arrived about the same time as us.

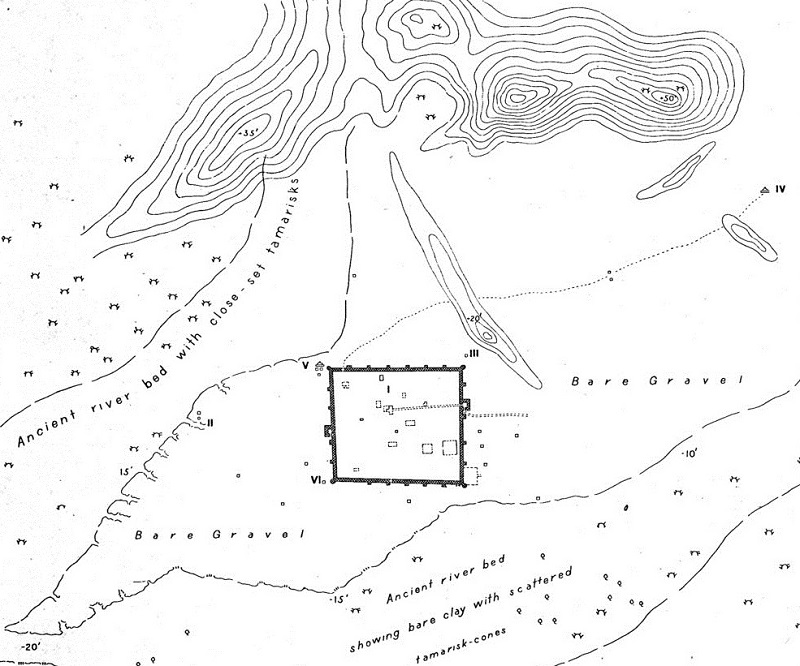

Detail of Aurel Stein's plan of Kharakhoto and its vicinity

M. A. Stein, Innermost Asia (1928) vol. 3 plan 17 : Sketch Plan of the Site of Khara-khoto

The Black City

Yesterday's clear sky has given way to a light sandstorm which has turned the sky to a grey haze and fills our mouths with the taste of desert. The sharp sand-filled wind threatens to wreak ruination upon our cameras, and yet the sandiness of our situation is only poorly reflected in the photographs we take as we head towards the western entrance to the Black City.

Distant view of Kharakhoto in a light sandstorm

As we approach closer, we see that huge drifts of sand have overwhelmed parts of the west wall, and workers are carrying material for repair and renovation up the sand dune onto the top of the wall.

Closer view of Kharakhoto in a light sandstorm

The main path leading to the west entrance of Kharakhoto

The main entrances in the west wall and the east wall are protected by a bastion which is entered from the side, but after we reach the inside of Kharakhoto through the west gate I realise that the bastion is no defence against the blustering wind.

Entering Kharakhoto through the west entrance

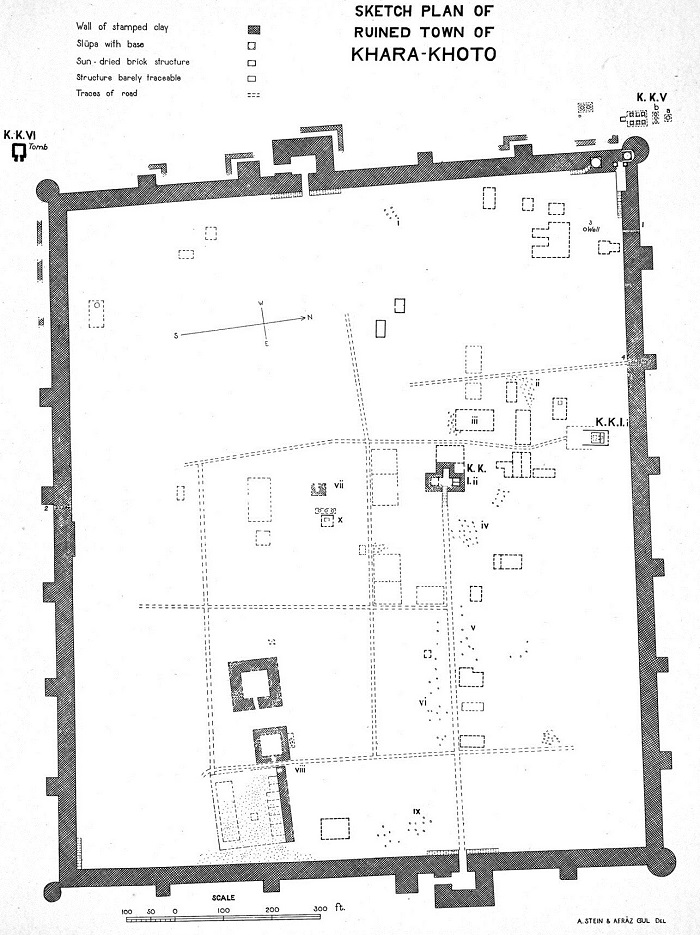

Aurel Stein's plan of the city of Kharakhoto

M. A. Stein, Innermost Asia (1928) vol. 3 plan 18 : Sketch Plan of the Ruined Town of Khara-khoto (west at top)

(North wall 435 m; East wall 370 m; South wall 420 m; West wall 370 m)

A few years back it was possible to wander freely around the site, but now all the ruins and other features are surrounded by wooden fences, and a carefully laid-out wooden walkway meanders across the city, allowing the few visiting tourists to safely pass by all the main features without touching. The walkways are roped in on either side, and we are encouraged not to stray from the chosen path by strategically placed surveillance cameras on tall posts. But the desert sands show no respect for human plans, and in many places the pathway is submerged by drifts of sand which we have to wade through. We dutifully follow the walkway eastwards across the interior of the city, passing by the ruins of massive mud-built buildings and the single Western Xia stupa still standing inside the city ("x" on Stein's plan).

Ruins of the Archives (架閣庫) just northeast of the main gate

Western Xia stupa from the south (Buddhist temple in the background)

Closer view of the Western Xia stupa

Remains of a large building in the southeast

Everywhere pottery fragments large and small are scattered on the ground and in the sand

Large pottery fragment in the sand

East entrance of Kharakhoto

East of the city huge sand dunes stretch as far as the eye can see. On Stein's 1914 sketch plan of the Kharakhoto site the area east and northeast of the city is marked as "bare gravel", and even on Google Maps you can clearly see the outlines of the ruins of many buildings under what is now the shifting sands of the Gobi Desert. There is also an outlying stupa, 375 metres northeast of the northeast corner of Kharakhoto ("IV" on Stein's plan, see Innermost Asia illustration 256), but it looks to be impossible to reach now.

Google Maps view of the east of Kharakhoto

{Map data ©2019 Imagery ©2019 DigitalGlobal}

(The stupa is the circle at the top right corner)

Outside the east wall of Kharakhoto with the Gobi Desert behind me

After exploring the area outside the east wall, we return back into the city through the east entrance, but the sand finally gets into my camera, and for a while the shutter is stuck half closed until I manage to clear the sand grains away. We head westwards towards the northwest corner of the city where modern renovations of five Yuan dynasty stupas stand guard over the city. By the time we reach them the wind has calmed and the sky has cleared.

View of the interior of Kharakhoto from the east entrance

On the way to the northwest corner we pass close to the Western Xia stupa we saw earlier, and from this angle it turns out to be the remains of a triple stupa, with one large stupa in the centre and two smaller (now almost vanished) stupas on either side.

Remains of the Western Xia triple stupa

Close to the northwest corner there is an irregular hole in the north wall, which is reputed to have been made by the Mongol garrison when under besiege by the Ming army in 1372, either in order to sally forth to attack the enemy or in order to effect an escape from the doomed fortress. Nearby is a well where the Mongol forces are said to have buried their wives, children and treasure before they went out to fight the final battle.

Hole in the north wall near the northwest corner

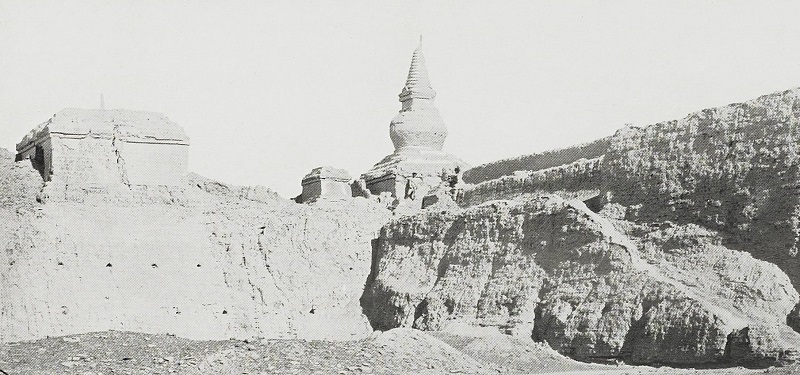

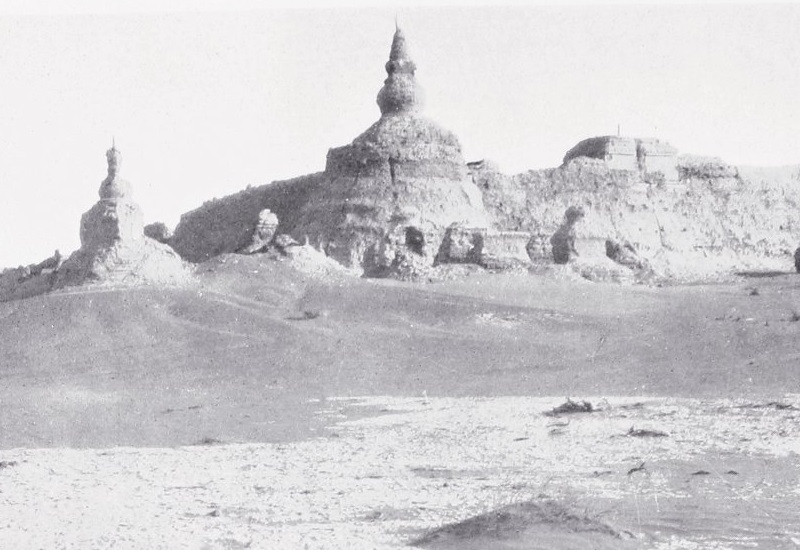

The five stupas on top of the walls at the northwest corner are the most impressive and iconic feature of Kharakhoto. There are two large stupas, two medium-sized stupas, and one small stupa, all of which are thought to date to the Yuan dynasty, but have been extensively renovated in recent times. Aurel Stein's photograph from 1914 shows that only the large corner stupa was whole at that time, and that just the bases remained for the four other stupas.

Northwest corner of Kharakhoto with five stupas

Aurel Stein's 1914 photograph

248. Ruined stūpas built above north-west corner of circumvallation, Khara-khoto.

M. A. Stein, Innermost Asia (1928) vol. 1 Fig. 248

There are steps up to a viewing platform on two levels next to the stupas, and although a large wooden gate part way up the steps is firmly padlocked shut, we can easily climb round the obstacle to reach the viewing platform where there is a fine view over the interior of the city and the stupas on the top of the walls.

On the viewing platform at the northwest corner

Closer views of the renovated Yuan dynasty stupas

Looking down across the interior of Kharakhoto from the viewing platform

Looking south along the west wall

Looking east along the north wall

Looking back at the northwest corner on the way to the west entrance

Outside the west wall again, but now with a clear blue sky, we first explore to the north where the modern renovations of five Yuan dynasty stupas on the walls look proudly down on the remains of a cluster of ten or so unrenovated Yuan dynasty stupas outside the wall. The information pedestal informs us that the stupas outside the northwest corner had been destroyed by treaure-hunting foreigners during the early 20th century, but at least the outlying northernmost stupa appears to be whole in Stein's photographs.

Northwest corner with five renovated Yuan dynasty stupas

The two largest stupas on the wall

When the Swedish archaeologist Folke Bergman (1902–1946) visited Kharakhoto in 1931 the northwest corner looked rather different than it does today. The photograph below, taken from about the same position as my photograph above, shows that the large stupa on the right was just a stump, which agrees with Aurel Stein's 1914 photographs. Strangely on the left, just opposite the hole in the wall, there is a large stupa which there is no trace of today.

Folke Bergman's photograph of the northwest corner of Khara-khoto in January 1931

a. The north-western corner of Khara-khoto with a stupa crowning the angle-tower

Folke Bergman, Travels and Archaeological Field-Work in Mongolia and Sinkiang: A Diary of the Years 1927-1934 (Stockholm, 1945) Plate 22a

Aurel Stein's 1914 photograph of the northwest corner from the north shows no sign of the stupa seen outside the hole in the wall in Bergman's photograph (the different perspective of Bergman's photograph makes the hole in the wall seem much closer to the corner stupa than it actually is). My only explanation for the mysterious stupa outside the north wall in Bergman's photograph is that it is actually the Yuan dynasty stupa on the far right of Stein photograph below (my photograph labelled "The outlying northernmost stupa"), and that some weird trick of perspective makes it appear much closer to the city walls than it really is.

Aurel Stein's 1914 photograph

241. North-western corner of circumvallation of Khara-khoto, with stūpas outside, seen from north.

M. A. Stein, Innermost Asia (1928) vol. 1 Fig. 241

The large corner stupa

Ruins of Yuan dynasty stupas outside the northwest corner

Cluster of ruined stupas

Looking north at the ruined stupas

The outlying northernmost stupa

Next we go down to the southwest corner of the city, where there is a well-preserved Islamic tomb (or possibly a mosque) a short distance from the corner of the walls. And then about half way along the south wall of Kharakhoto is the remains of a solitary Buddhist stupa.

Islamic tomb or mosque (view from the northwest)

Islamic tomb or mosque (view from the west)

Islamic tomb or mosque (view from the south)

Remains of a solitary Buddhist stupa

The Celebrated Suburgan

After having spent nearly three hours wandering around the inside and outside of the city, we make our back towards the visitor reception area, but turn north to make our pilgrimage to the most sacred site at Kharakhoto, the "celebrated" or "famous" suburgan (sepulchral stupa) that is situated 150 metres due north of the reception area. It was here that Kozlov discovered thousands of texts (mostly in the Tangut language), paintings, statues and other artefacts, as well as the skeleton of a seated person (whose skull was taken back to Russia but mislaid during the Siege of Lenningrad). These were sealed inside the stupa during the Western Xia period, and are by far the largest and most important cache of Tangut texts and artefacts ever to have been discovered. The texts are now held at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in Saint Petersburg, and many paintings and statues from the stupa can be seen at the Hermitage Museum online collection (search for "Khara-Khoto").

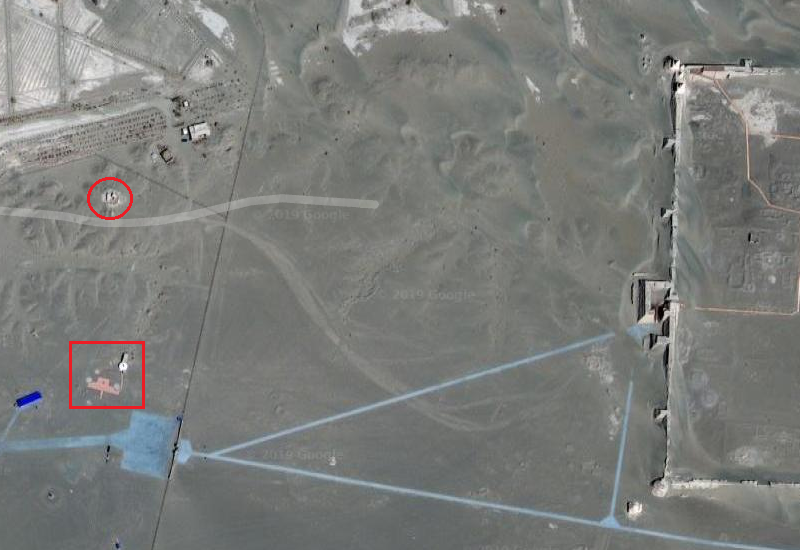

Google Maps view of the west of Kharakhoto

{Map data ©2019 Imagery ©2019 DigitalGlobal}

(The visitor reception area is highlighted by a red square, and the remains of the stupa by a red circle)

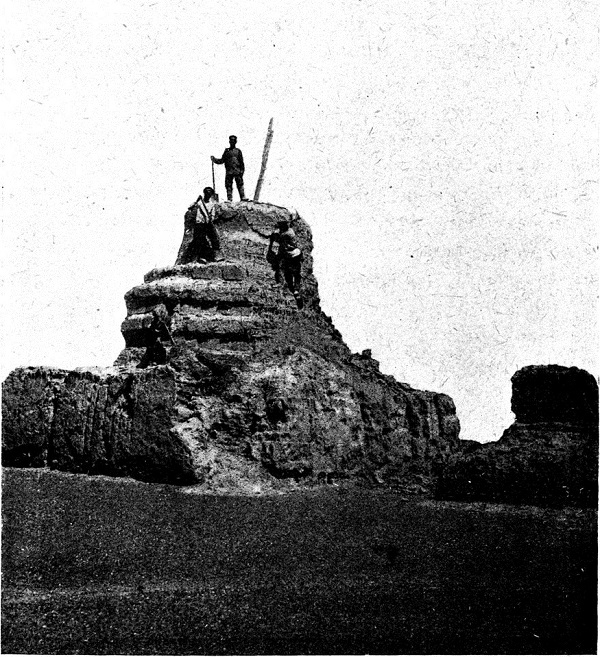

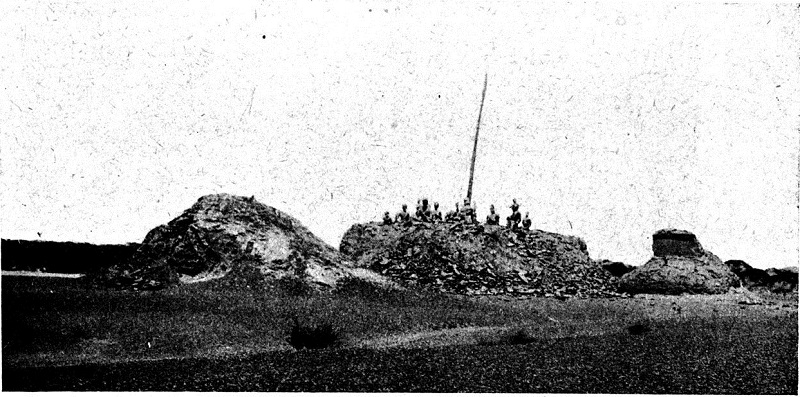

Kozlov's team destructively excavated the stupa during June 1909, leaving behind just the platform that the stupa was built on. When Stein arrived at Kharakhoto five years later he was horrified by the scene of devastation that greeted him, and he expressed his dismay at the state of Kozlov's excavation in no uncertain terms:

A structure quite different in type from these Stūpas and of far greater interest was the ruin, K.K. II, which was pointed out to me on my arrival at the site as the place where Colonel Kozlov in 1908 had secured his great haul of manuscripts, paintings and other antiques. It was situated close to the bank of the western river-bed and about two furlongs to the west of the western gate of the town, and presented, as seen in Figs. 257, 258, a scene of utter destruction. All that could be made out on first inspection was a brick-built platform about 28 feet square and 7 feet high, and on its sides heaps of debris of masonry and timber, mixed up in utter confusion with fragments big and small of stucco, originally painted and evidently once forming part of clay images. Frames of wood and reed bundles, which had served as cores for statues, lay about on the slopes and all round on the gravel flat. All these remains had obviously suffered greatly by exposure after having been thrown down. But even a slight scraping below the surface sufficed to show that, while the remains of paper manuscripts and prints had been reduced, where exposed, to the condition of mere felt-like rags, below the outer layer of debris they were still in fair condition. The careful clearing and sifting of all the ‘waste’ left behind in this sad condition by the first explorers of the ruin occupied us for fully a day and a half.

The celebrated suburgan on 12 June 1909 (at start of excavation)

P. K. Kozlov, Mongolia and Amdo and the dead city of Khara-khoto (1923) p. 551

The celebrated suburgan on 20 June 1909 (at end of excavation)

P. K. Kozlov, Mongolia and Amdo and the dead city of Khara-khoto (1923) p. 552 (close-up of statues)

The celebrated suburgan in May 1914

258. Debris covering slopes of base of destroyed stūpa, K.K. II, Khara-khoto.

M. A. Stein, Innermost Asia (1928) vol. 1 Fig. 258

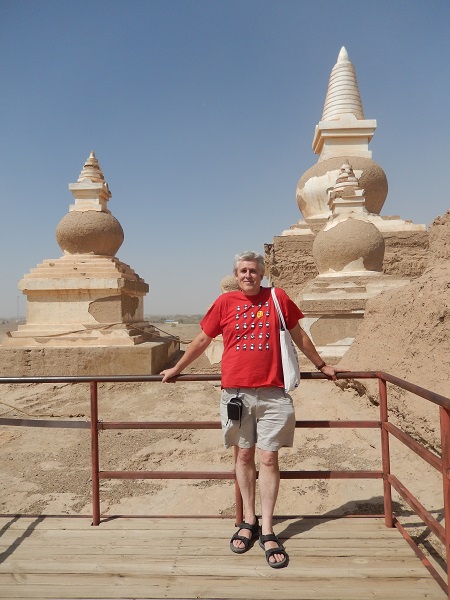

The celebrated suburgan in August 2016

Standing between the two parts of the stupa base

The Golden City

We finally return to our waiting driver, and take our leave of Kharakhoto. After about ten minutes we stop by the remains of some ruins on low hill overlooking the dried riverbed, about 4 km northwest of Kharakhoto. Kozlov called these ruins the "citadel of Altan-khoto" (Altan-khoto means "Golden City" or "Golden Fort" in Mongolian), and stated that according to legend they housed the cavalry guard for Khara-khoto. The information tablet tells us that it is called Datongcheng 大同城 (Datong City or Datong Fort), and that it is a defensive position that was originally founded during the Northern Zhou dynasty, in about 561–565, and was rebuilt during the Tang dynasty in the year 743. It does not tell us whether it was still in use during the Western Xia or Yuan periods.

The satellite image clearly shows a square outer wall (200 × 200 metres), with the northern part completely swept away by the dead river to its north, and the square wall of a single large building (75 × 75 metres) in the middle. However, on the ground the layout of the fort is not so easy to see as the sand covers many of the low sections of wall, and there are only a few disjoined sections of outer wall and inner building that still stand above the sand.

Google Maps view of Datongcheng and Kharakhoto

{Map data ©2019 Imagery ©2019 DigitalGlobal}

(Datongcheng is 4 km northwest of Kharakhoto as the crow flies, or about 5.5 km along the road)

View of Datongcheng from the south

View of the southeast corner of the inner building from the south

View of the southeast corner of the inner building from a gap in the middle of the south wall

The Red City

About 6 km west-northwest of Datongcheng as the crow flies, or about 10 km by road, is another defensive fortification that we stop to see. This is a well-preserved reddish mud-built fort (20 × 22 metres), known fittingly as the Red City or Red Fort (Hongcheng 紅城), which is situated about 400 metres east of the road to Kharakhoto, near a scenic attraction known as Guaishulin (怪樹林 "strange trees"), which is a stretch of dead trees with trunks and branches twisted into fantastic shapes. The Red Fort was part of a series of defensive fortifications known as the Juyong Forts (居延城) which were established during the Western Han in 102 BC, and were abandoned at the end of the Eastern Han.

Google Maps view of Hongcheng, Datongcheng and Kharakhoto

{Map data ©2019 Imagery ©2019 DigitalGlobal}

(The current course of the Black Water or Etsin Gol can be seen to the west of Hongcheng)

View of Hongcheng from the south

View of Hongcheng from the southwest

View of Hongcheng from the southeast

View of Hongcheng from the northeast

Inside of Hongcheng

Gate in the east wall of Hongcheng

And now we head back to Dalaihob in order to catch the overnight train to Hohhot for the next stage of our expedition.

Ancient Cities | Inner Mongolia | Stupas | Western Xia

Index of Rambling Antiquarian Blog Posts

Rambling Antiquarian on Google Maps