Diary of a Rambling Antiquarian

Saturday, 30 September 2017

Qingzhou White Pagoda and Qingling Mausoleum

The week-long meeting I was attending in Hohhot ended on Friday, and I have a few days free to go travelling in Inner Mongolia. I had originally intended to spend a week travelling eastwards across Inner Mongolia, then south to Chifeng, and then back to Beijing, visiting various Khitan and Jurchen sites of interest. However, for reasons which I will explain later I decided to curtail my travels in Inner Mongolia, and just visit Bairin Right and Left Banners for a couple of days, before returning to Hohhot on Tuesday. I am catching the 18:05 train from Hohhot East, arriving at Daban (大板), seat of Bairin Right Banner (巴林右旗), early on Saturday morning. What I did not realise was that this is the start of the "golden week" National Day holiday, and all the students studying in Hohhot are heading back home for the holiday week, so the only ticket I have been able to buy is a standing ticket. Often I can upgrade to a sleeper berth on the train, but not today, and so I pass the night alternately standing and perching on the edge of a seat. But it is only a twelve hour journey, and I have been seatless on trains in China for much longer than this. For the ten days that I had been staying at Hohhot I hardly heard anyone speaking Mongolian, so it is a real joy for me that on this train full of students returning to their homes in the far-flung corners of Inner Mongolia, the majority of them are talking in Mongolian rather than Chinese.

Students alighting from the train early in the morning at Daban station

I want to visit the famous White Pagoda of Qingzhou (Qìngzhōu Báitǎ 慶州白塔) which is situated at the modern settlement of Suoboriga Sumu (索博日嘎苏木), 75 km north of Daban (and closer to 100 km by road), but I am not sure how to get there. I read that there is a daily bus, but the timings are not convenient for getting there and back in a day, so I head towards the taxis at the front of the station to see if I can hire a taxi to take me. As luck would have it, the very first taxi I approach is heading that way, and I can share the ride with a local man for what I think is a very reasonable price. My fellow pasenger tells me that I am being ripped off, but I expect to pay more than the locals, and have no complaint. "Suoboriga Sumu" is a bit of a mouthful, so the locals call the place simply Baitazi (白塔子) after its white pagoda, although my driver pronounces it as Beitazi in his dialect of Mandarin.

View from the car on the road to Baitazi

The road is much quicker than I had imagined, and in well under two hours we have reached Baitazi, and are parked outside the entrance to the pagoda in the northwest corner of the ancient city of Qingzhou, which is preserved undisturbed by modern development. The city of Qingzhou was established in order to service the Qingling Mausoleum (慶陵) in the nearby mountains where Emperors Shengzong 聖宗 (r. 982–1031), Xingzong 興宗 (r. 1031–1055), and Daozong 道宗 (r. 1055–1101), the 6th, 7th and 8th emperors of the Liao dynasty (916–1125), are buried.

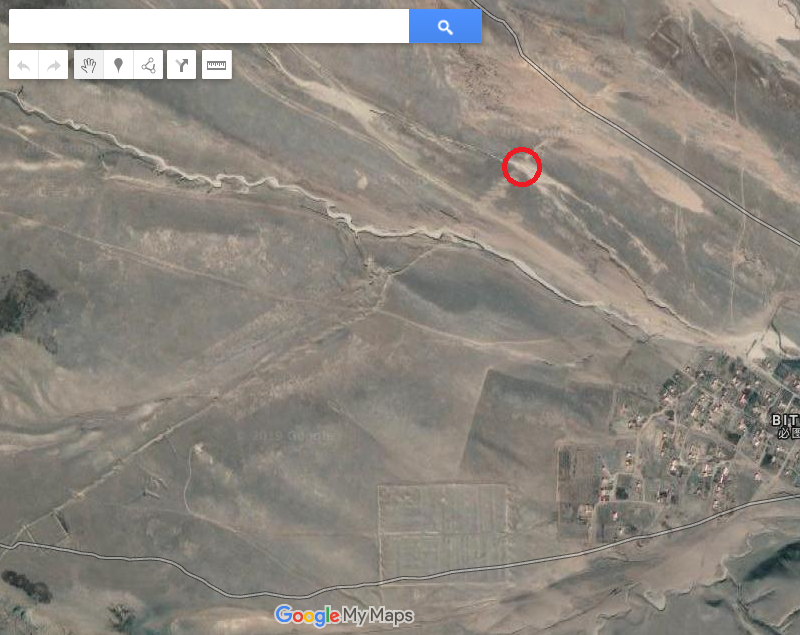

Google Maps view of Qingzhou

{Map data ©2019 Imagery ©2019 DigitalGlobal}

(The red tag marks the White Pagoda)

Parked in front of Qingzhou White Pagoda

My taxi is the green and white car; the other car belongs to the pagoda-keeper (I want that job!)

Qingzhou White Pagoda

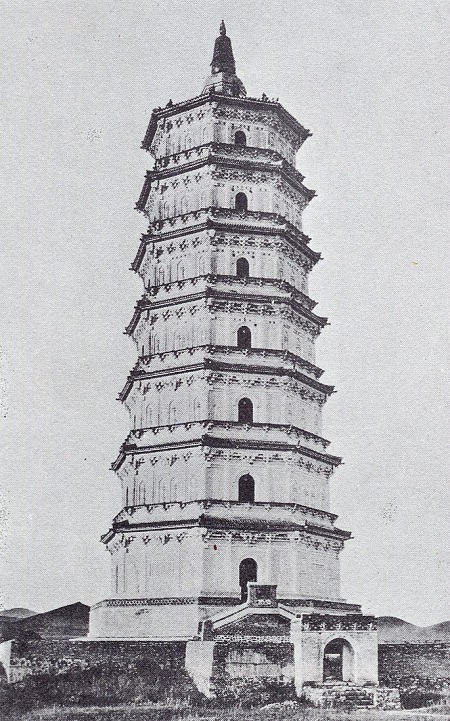

The proper name for the Qingzhou White Pagoda is the Shakyamuni Śarīra Pagoda (釋迦牟尼舍利塔), which is inscribed on a board on the front of the pagoda. It is an octagonal seven-storey pagoda, 73 metres high, with entrances on the first storey on the four cardinal sides, and wooden shuttered windows on the other six storeys on each cardinal side. However, unlike the White Pagoda at Hohhot, there is no corridor running around the circumference of each floor, and there are no staircases to other floors, just a short tunnel between the doors on the first storey if I understood the pagoda-keeper's explanation correctly. As the pagoda cannot be ascended by visitors, it is not likely that there will be inscriptions on the wall as is the case with the Hohhot White Pagoda. Nevertheless, I really would like to take a peek inside if I can. The entrances on the north, east and west sides seem to be completely closed off (or maybe they are false entrances), but the entrance on the south has a wooden doorway with a padlock that appears not to be secured and doors which have been tantalisingly left slightly ajar. But after some careful reflection I decide that it would not be a good idea to try to climb up over an overhanging ledge more than six feet above the base of the pagoda in order to gain illicit entry (from the graffiti scrawled on the north entrance it is clear that not all visitors to the pagoda share my compunctions), so I content myself with viewing this spectacular pagoda from the outside.

Views of the White Pagoda from the south

Old photograph of the White Pagoda

Source: Laurence Sickman and Alexander Soper, The Art and Architecture of China (The Pelican History of Art, 1971) p. 446 fig. 298

Pagoda undergoing renovation in 1989

Stupa in front of the White Pagoda

Southeast side of Qingzhou White Pagoda

Northeast side of Qingzhou White Pagoda

Southwest side of Qingzhou White Pagoda

1st storey of the southwest side of the Qingzhou White Pagoda

2nd storey of the southwest side of the Qingzhou White Pagoda

3rd storey of the southwest side of the Qingzhou White Pagoda

North side of the Qingzhou White Pagoda

Shame on the ironically named Wang Quanliang (王全良) "Wang Completely Good" and his fellow graffitists!

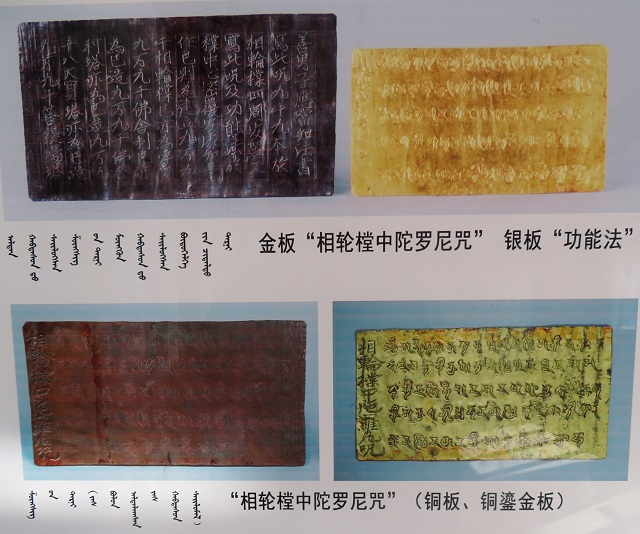

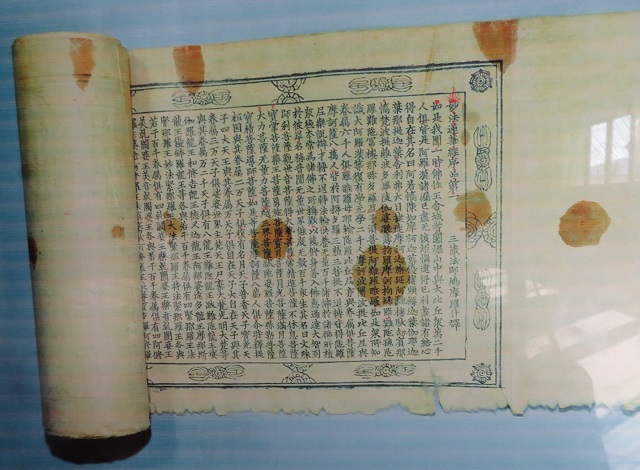

During the renovation of the pagoda in 1989, a number of Buddhist manuscript and woodblock printed sutras, as well as gold, silver, and bronze plates inscribed with dhāraṇī texts, were found inside the pagoda finial (相輪樘). 108 painted wooden stupa models, each containing a printed dhāraṇī slip, were also discovered at the top of the pagoda.

Gold, silver, and bronze dharani plates found in the pagoda

Lotus Sutra scroll found in the pagoda

Qingling Mausoleum

After viewing the pagoda, I go back to the small exhibition room by the main entrance, and as it shows pictures of the imperial tombs at the Qingling mausoleum (慶陵) I ask the pagoda-keeper if it is possible to go there. He replies that they are in a protected area that is not open to the public, but after further probing he suggests that he might be willing to take me there in his car for a not-so-small fee. I wonder if my taxi driver can take me there, but he is from Daban and does not know the way, and anyway the pagoda-keeper assures me that he would not be allowed into the restricted area. So in the end my taxi driver and me pile into the pagoda-keeper's car, and off we go.

On the way we stop to take a look at the remains of the earthen boundary wall (金界壕遺址) that marked the furthest extent of the territory of the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). I don't have a GPS-enabled camera with me on this trip, but I think that the circled location on the satellite map below is where we crossed the earthen wall (running from southwest to northeast). On the bottom left and the top right of the satellite image there are the outlines of what appear to be two wall forts (each 100 m × 100 m) some 2.5 km apart, and there is a large rectangular structure just east of the modern settlement of Bitu, as well as another rectangular structure a couple of kilometres northwest of the wall (not shown in the image below).

Google Maps view of Jin dynasty earthen boundary wall just northeast of Bitu

{Map data ©2019 Imagery ©2019 DigitalGlobal}

The wall runs from southwest to northeast, with wall forts at the bottom left and top right of the image

Jin dynasty earthen boundary wall

The rough ground in the foreground of the photographs is the "road" to the Valley of the Royal Tombs (王墳溝).

When we reach the entrance to the Valley of the Royal Tombs Managed Protection Area (王坟沟管护区), which does indeed seem to prohibit unauthorised traffic from entering, the pagoda-keeper negotiates our entrance with the gatekeeper. While he does so, I take a look at an interesting dharani pillar with Sanskrit inscriptions that stands by the entrance.

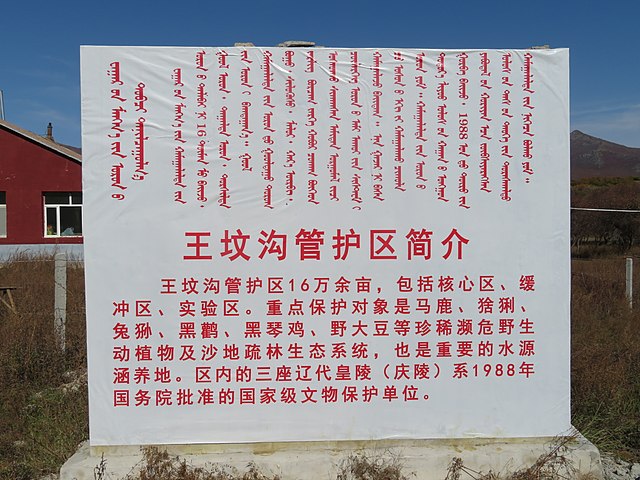

Sign at the entrance to the Valley of the Royal Tombs Managed Protection Area

王坟沟管护区简介

The octagonal dharani pillar is made from white marble (漢白玉), and was originally sited at the Yongxing Mausoleum (永興陵), on the west side of the middle section of the spirit path (神道) leading to the tomb of Emperor Xingzong. The pillar originally stood on a Mount Meru base (須彌基座) surmounted with lotus decoration, and was covered by an octagonal canopy topped with a stupa-like finial. However, now only the body of the pillar remains. The Sanskrit dhāraṇī are clearly preserved on one side only, and floral decoration is still fresh on the top of another face.

Dharani pillar from the tomb of Emperor Xingzong of Liao

Side of the dharani pillar with clearest Sanskrit inscription

Detail of floral decoration on the dharani pillar

We drive for ten more minutes until we reach an impassable river, then turn to follow the river westwards a short distance before parking on the grass. From there we climb up the gentle slope south of the river where there is a good vantage point for viewing the imperial tombs on the other side of the valley. To get to them you have to ford the river and walk for about an hour, but as the pagoda-keeper's car is not up to crossing rivers, and he is eager to get back to his pagoda, it is not possible to get a close look at the tombs today, and I have to content myself with the view from a distance. The tombs are each in a small valley coming down the mountainside on the opposite side to us. The tomb of Emperor Shengzong (Yongqing Mausoleum 永慶陵) is on the right, the tomb of Emperor Xingzong (Yongxing Mausoleum 永興陵) is in the middle, about 600 m west of Shengzong's tomb, and the tomb of Emperor Daozong (Yongfu Mausoleum 永福陵) is on the far left, about 1,400 m west of Xingzong's tomb. Unfortunately I omitted to take a photograph of a photograph at the White Pagoda showing the exact positions of each tomb on the mountainside.

View of the tombs of Emperors Shengzong, Xingzong and Daozong of Liao

View of the tombs of Emperors Shengzong and Xingzong of Liao

Tomb of Shengzong is in the valley on the right

Tomb of Xingzong is in the valley on the left

Tomb of Daozong is off the picture to the left

In the Valley of the Tombs of the Liao Emperors

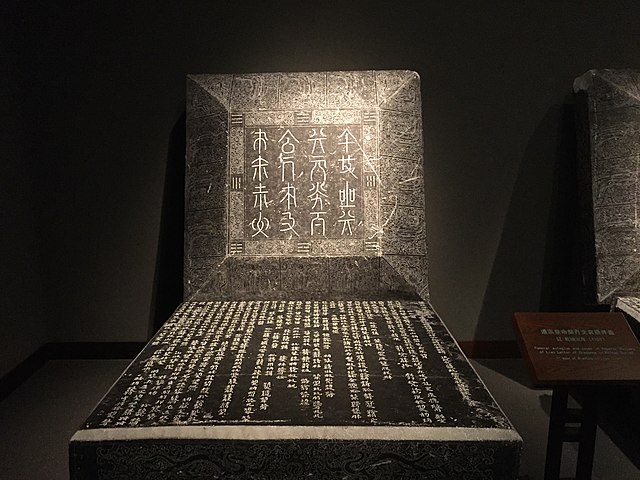

In the 1930s, the memorial tablets in Chinese and Khitan for Emperor Shengzong his consort Empress Rende (仁德皇后), Emperor Xingzong and his consort Empress Renyi (仁懿皇后), and for Emperor Daozong and his consort Empress Xuanyi (宣懿皇后), were unearthed from the Qingling tombs. Four of the tablets were written in Khitan Small Script (those for Emperors Xingzong and Daozong and their consorts). Most of these memorial tablets are now held at the Liaoning Provincial Museum in Shenyang, but the Khitan Small Script memorial tablets for Emperor Xingzong and Empress Renyi were reburied at the Qingling tombs, and have not yet been rediscovered.

Epitaph in Khitan Small Script for Empress Xuanyi (1040–1075)

It is early afternoon now, and the pagoda-keeper drives us back to the White Pagoda, where I transfer to the taxi to take me back to Daban. My plan is to visit the Bairin Museum in Daban which holds a Khitan Small Script epitaph and a Khitan eulogy, and then catch the late afternoon train to Lindong where I have a hotel booked. However, it is not much further from here to Lindong as it is to drive back to Daban, so I change plans, and decide to drive to Lindong, stopping off at the Zuzhou Stone House on the way.

Dharani Pillars | Inner Mongolia | Liao dynasty | Pagodas | Tombs

Index of Rambling Antiquarian Blog Posts

Rambling Antiquarian on Google Maps

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)