BabelStone Blog

Tuesday, 1 January 2008

Zhang Zhung Royal Seal

Regular readers will remember that last summer I was looking at the various Zhang Zhung Scripts associated with the Tibetan Bon tradition, and in particular I was interested in the sMar chen སྨར་ཆེན style of script, for which I created a test font. One of the problems in studying these scripts is a paucity of materials written in the scripts themselves other than tables of letters that are given in various calligraphy books.

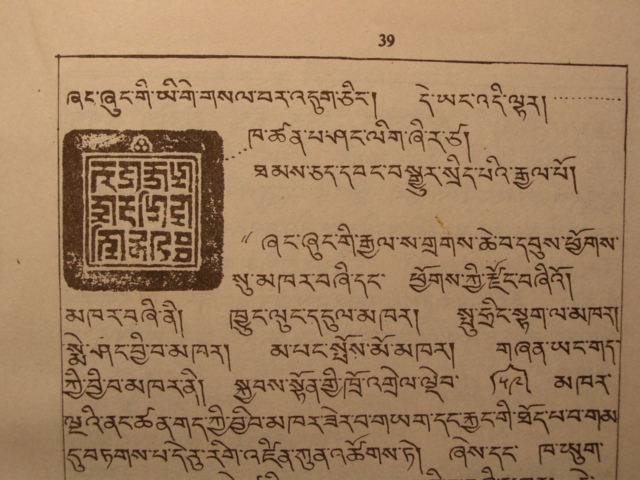

However, there is one historical artefact that does have an inscription in the sMar chen script. This is a seal that is now held at the Menri Monastery at Dolanji in India (presumably originally from its namesake in Tibet). As far as I know there aren't any published photos of the seal, but it is discussed by Lopön Tenzin Namdak སློབ་དཔོན་བསྟན་འཛིན་རྣམ་དག (1927-), in his history of Bon, snga rabs bod kyi byung ba brjod pa'i 'bel gtam lung gi snying po སྔ་རབས་བོད་ཀྱི་བྱུང་བ་བརྗོད་པའི་འབེལ་གཏམ་ལུང་གི་སྙིང་པོ། (Dolanji, 1983), where he provides a copy of the seal imprint :

According to Tenzin Namdak this is a royal seal of the Lig-myi-rhya dynasty (Lig-mi-rgya in later sources), the last kings of the Zhang Zhung kingdom during the 7th century. The historical sources are notoriously confusing, and there is a good deal of uncertainty about the kings of Zhang Zhung—it used to be thought that Lig-myi-rhya was the name of a particular king (or perhaps more than one king), but now scholarly opinion seems to be that this is the title assumed by the Zhang Zhung kings, corresponding to Tibetan srid pa'i rje "'Lord of Life". Without having even seen a picture of the actual object itself, it is difficult to make a judgement as to whether this seal does indeed date back to the time of the Zhang Zhung kingdom or whether it is the work of a later age, though even if it is a later reproduction (as the sceptical mind will no doubt suspect) it is always possible that the inscription on it may be a copy of a genuine Zhang Zhung title.

The inscription on the seal is in the sMar chen script, reading in three horizontal lines and comprising twelve glyphs (eleven consonant letters with or without a vowel mark, folllowed by a shad mark). Tenzin Namdak transliterates the inscription into Tibetan script as :

ཁ་ཚན་པ་ཤང་ལིག་ཞི་ར་ཙ།

kha tshan pa shang lig zhi ra tsa

Note that this is not in the Tibetan language, but is presumed to represent the ancient and extinct Zhang Zhung language that was spoken in the area of Western Tibet where the Zhang Zhung regime held sway. Tenzin Namdak translates this into Tibetan as :

ཐམས་ཅད་དབང་བསྒྱུར་སྲིད་པའི་རྒྱལ་པོ།

thams cad dbang bsgyur srid pa'i rgyal po

"Wielding Power Over All, King of Life"

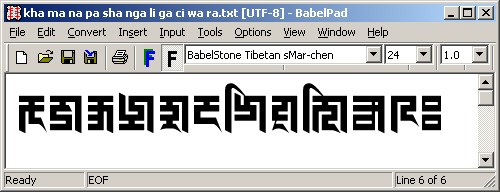

My reading of the sMar chen inscription differs somewhat from that of Tenzin Namdak, so the first thing we ought to do is try to identify the actual glyphs that the inscription comprises. When reading sMar chen text it is important to realise that, unlike the Tibetan script, it has no syllable separation mark, so it is not possible to mechanically determine whether a consonant is syllable-initial or syllable-final, and so Tenzin Namdak is making a lexical judegment when he syllabifies the inscription as kha tshan pa shang lig zhi ra tsa rather than kha tsha na pa sha nga li ga zhi ra tsa or with some other syllabification. So at this stage I will read each glyph as a separate syllable with either an inherent a vowel or an explicit i, u, e or o vowel. My reading of the individual glyphs of the inscription is kha ma na pa sha nga li ga ci wa ra (followed by a shad mark), which when written out with my BabelStone Tibetan sMar-chen font (now replaced by BabelStone Marchen) looks like :

𑱳𑲁𑱽𑱾𑲌𑱵𑲋𑲱𑱴𑱶𑲱𑲅𑲊𑱱

Unicode Marchen text displayed with my BabelStone Marchen font (vowel signs may not render correctly)

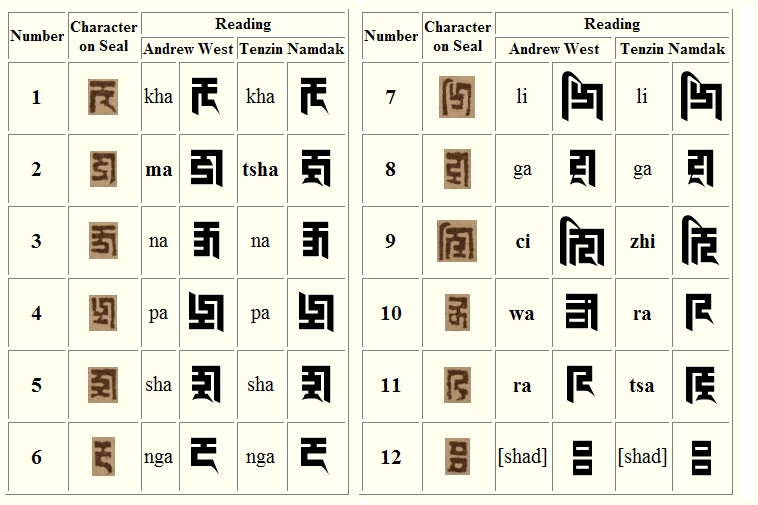

Comparing Tenzin Namdak's transliteration with mine, we differ in our readings of glyphs 2 (ma versus tsha), 9 (ci versus zhi), 10 (wa versus ra) and 11 (ra versus tsa), as can be seen in the table below :

I think that it is clear that glyph 2 is ma not tsha, and glyph 9 is ci not zhi, and that Tenzin Namdak's readings of these two glyphs are either errors or deliberate corrections. The reading for glyph 10 is a little more problematic as it is not very clear from the image of the seal imprint what grapheme it is intended to represent. Nevertheless, it does seem to me that glyph 10 cannot possibly be ra, and my reading of wa (or possibly we, with an e vowel sign above a reduced letter wa) is much more plausible. As to glyph 11, I suppose a case could be made for interpreting it as rather deformed letter tsa, but I think it is simpler and more reasonable to read it as ra with a little flick-back of the final stroke.

To understand why Tenzin Namdak is deliberately misreading or correcting the inscription we need to try to interpret what it means, and to do this requires a knowledge of the Zhang Zhung language that it is supposedly written in. Unfortunately our knowledge of the Zhang Zhung language is not great, being based largely on a single (not entirely) bilingual Tibetan and Zhang Zhung text, the mDzod Phug མཛོད་ཕུག, supplemented by translations of titles of Tibetan texts and various snippets preserved here and there. Luckily for us my good friend Dan Martin has made available a critical edition of the mDzod Phug, as well as a Zhangzhung Dictionary that synthesizes his own work on the mDzod Phug as well the lexicographical work of other Zhang Zhung scholars. It is Dan's dictionary (April 2004 edition) that I use as my main source for interpreting the inscription.

Glyphs 1-3 (kha ma na)

Tenzin Namdak's reading for these three glyphs is kha tshan, which he translates as Tibetan thams cad "all, everything". However, there are two big problems with this. Firstly, the second glyph is clearly ma not tsha, and secondly, even after correcting ma to tsha the resultant word kha tshan does not correspond to Tibetan thams cad. In fact, kha tshan does not appear in the Zhang-zhung Dictionary, and the Zhang Zhung word correspondng to Tibetan thams cad in the mDzod Phug is tha tshan. Thus, in order to get the required meaning we would need to correct kha to tha as well, which I think is a correction too far. But what are the alternatives ? Well, if we accept the three glyphs without any corrections there are three possible syllabifications :

kha ma na

Looking at the Zhang-zhung Dictionary, this does not seem to make any sense, and can be discounted.

kham na

kham corresponds to Tibetan sog pa "shoulder-blade, scapula", and na is a "locative" particle, which I think can also be discounted.

kha man

Although kha man does not occur in the Zhang-zhung Dictionary, there are a couple of words which are quite close :

- kha mar or kha mur, which corresponds to Tibetan rig pa "knowledge, understanding"

- kha mun, which corresponds to Tibetan 'dod khams "the world of sensual pleasures"

In the context of the rest of the inscription, the second of these looks most promising to me. As a~u vowel alternation is quite common in the Zhang-zhung Dictionary (cf. kha mar~mur), kha man and kha mun could conceivably be variant spellings of the same word, and the result would at least make sense grammatically: "King of Life Wielding Power over the World of Sensual Pleasures". But not being a student of Bon (or Buddhism) I do not know whether this would make sense in the context of an inscription on the seal of a Zhang Zhung king.

Glyphs 4-6 (pa sha nga)

Tenzin Namdak syllabifies these three glyphs as pa shang, which corresponds to Tibetan dbang sdud "to bring under one's power" in the Zhang-zhung Dictionary, and which he translates by the Tibetan dbang bsgyur "to have power to transform, command". This seems reasonable.

Glyphs 7-9 (li ga ci)

Tenzin Namdak syllabifies these three glyphs as lig zhi, corresponding to Tibetan srid pa "life, existence, world". This looks very promising, except for the fact that the inscription actually has ci rather than zhi, and although there is only one stroke difference between the two letters, to correct ci to zhi would imply that the engraver of the inscription was incompetent (unlikely if it was a genuine Zhang Zhung period seal) or the seal is a fake. The other possibility is that lig ci is a variant spelling of lig zhi; although this is unattested, there are so many variant spellings of almost every word in the Zhang-zhung Dictionary that it seems quite plausible.

Glyphs 10-11 (wa ra)

Tenzin Namdak reads these two glyphs as ra tsa, which on the face of it is unreasonable. What I think he is doing is reading glyph 10 as tsa and glyph 11 as ra, and then reversing them to get ra tsa as a loanword from Sanskrit rāja "king". This really troubles me as glyph 10 does not look anything like tsa, and reversing glyphs 10 and 11 suggests that there is something seriously wrong with the inscription. Furthermore, ra tsa (or anything similar) is not otherwise attested in Zhang Zhung text—although it is included in Siegbert Hummel's "Materialen zu einem Wörterbuch der Zan-zun-Sprache" (Monumenta Serica vol. 31 [1974-1975]), that may be on the basis of this seal (I haven't read it so I'm just guessing).

I think by far the simplest explanation is to read these two glyphs as war, and assume this is a variant spelling of the common Zhang Zhung word wer, which corresponds to the Tibetan rgyal "royal", rgyal ba "victor, conqueror", rgyal po "king", rgyal mo "queen", etc. It is even possible to read it directly as wer if you take the upper part of glyph 10 to be an e vowel sign.

So in summary, my provisional reading of the inscription is :

𑱳𑲁𑱽𑱾𑲌𑱵𑲋𑲱𑱴𑱶𑲱𑲅𑲊𑱱 kha man pa shang lig ci war (Marchen transcription)

ཁ་མན་པ་ཤང་ལིག་ཅི་ཝར། kha man pa shang lig ci war (Tibetan transliteration)

འདོད་ཁམས་དབང་སྡུད་སྲིད་པའི་རྒྱལ་པོ། 'dod khams dbang sdud srid pa'i rgyal po (Tibetan translation)

"Wielding Power over the World of Sensual Pleasures, King of Life" (English translation)

Index of BabelStone Blog Posts