BabelStone Blog

Sunday, 11 January 2015

Two Tangut Families Part 1 : Laosuo

One of the most enduring narratives of Tangut history is that after the death of Genghis Khan in 1227 the Western Xia state was annihilated and its people slaughtered in a fury of genocidal revenge for the Western Xia's perceived betrayal of Genghis Khan. Although this may ultimately have led to the extinction of the Tangut people and their language, the Tangut people were not suddenly wiped off the face of the earth in 1227, but continued to exist as one of the major ethnic groups living under the Mongol empire in China.

There is evidence of some migration of Tangut people away from the Tangut homeland of Hexi ("West of the Yellow River"), and into north China following the destruction of the Western Xia state. In particular, some Tanguts had supported the Mongols during the wars of conquest by Genghis Khan, and became military or civil officials under the Mongol Empire and later the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). In recent years two steles have been discovered in Hebei province that throw considerable light on the lives and careers of two particular Tangut families during the Yuan dynasty:

- In 1985 a large stele (3.85 m in height) was discovered in Baoding 保定, 90 miles south-west of Beijing. Erected in 1350, the stele records the lives of the Tangut official Laosuo 老索 (1188–1260) and four generations of his family in a long Chinese inscription on three sides;

- In 2013 a small stele (0.60 m in height) was discovered in Daming 大名 (the Northern Capital of the Northern Song), at the far south of Hebei. Erected in 1278, the stele records the lives of the Tangut official Xiaoli Qianbu 小李鈐部 (1191–1259) and three generations of his family in a long Chinese inscription on one side and a brief Tangut inscription on the other.

Location of the Steles for Laosuo and Xiaoli Qianbu

{Map data ©2015 AutoNavi, Google, SK planet, ZENRIN}

There is much in common between Laosuo and Xiaoli: both defected to the Mongols, and fought for Genghis Khan in his wars against the Jin and Western Xia states; both settled in northern China at the end of the wars; both held the position of Darughachi of the local province; and both had a non-Tangut wife. Another odd coincidence is that in both cases the stele was discovered 635 years after it had been erected.

In this post I discuss the Stele of Laosuo found in Baoding, and next week I will discuss the Stele of Xiaoli Qianbu found in Daming.

Stele of Laosuo (1350)

The Stele of Laosuo was found in November 1985 at Xiezhuang 頡莊 village on the west side of Baoding city in Hebei. It has a long Chinese inscription on three faces which commemorates the life of the Tangut official Laosuo 老索 (1188–1260) and four generations of his family, who lived in Baoding throughout the Yuan dynasty. Laosuo held the post of Darughachi of Baoding under Zhang Rou 張柔 (1190–1268), who in 1227 rebuilt and repopulated the devastated city of Baoding. The stele now stands in the Ancient Lotus Pond (Gu Lianhua Chi 古蓮花池) in the centre of Baoding, where I photographed it in December 2013. The stele consists of a tall body surmounted by a wide head with the title inscribed in Chinese seal script characters. The base on which the stele would have stood has not survived.

Head of the Stele of Laosuo

《大元敕賜故順天路達魯花赤老索神道碑銘》

Body of the Stele of Laosuo

3.85 × 0.95 m.

What suprises me most about this stele is that no-one had ever heard of Laosuo before its discovery. Such a large, imposing stele, with text composed and written by notable Yuan dynasty officials would suggest that Laosuo was held in high esteem at the Yuan court, yet there is no biography for him in the Yuan History. Indeed, there appears not to be a single mention of him or anyone with a phonetically similar name that fits his profile, which is quite unexpected given all his achievements listed on the stele. There are also no certain mentions of any of his sons, grandsons or great-grandsons in the Yuan History, although there are a few passing mentions of people with the same name. This total lack of historical recognition contrasts strongly with Xiaoli Qianbu, for whom there is a biography in the Yuan History (which also covers his son and grandson), even though Xiaoli Qianbu's stele is far less impressive than that of Laosuo. Laosuo and Xiaoli Qianbu both had similar careers and achievements, and both held a position as Darughachi of an important provincial city, so why Xiaoli Qianbu and his family were remembered by the compilers of the Yuan History but Laosuo and his family were entirely forgotten is a mystery.

Transcription

The stele has been badly weathered, and parts of the inscription are illegible. The transcription given below is based on that provided by Liang Songtao 梁松涛 in Study of the "Spirit Stele Inscription of Laosuo from Hexi" 《河西老索神道碑铭》考释 (Minzu Yanjiu 民族研究 2007.2). This is a long inscription, with 1,172 surviving characters, covering three sides of the stele. There is no visible inscription on the back of the stele, but it is possible that a shorter inscription in Tangut script was originally engraved on the back, as is the case with the stele of Xiaoli Qianbu.

Front Side

- 大元敕賜故順天路達魯花赤河西老索神道碑銘

- 翰林學士承旨榮祿大夫知制誥兼修國史歐陽玄奉敕撰文

- 集賢侍講學士中奉大夫兼國子祭酒蘇天爵奉敕書丹

- 翰林學士承旨榮祿大夫知制誥兼修國史張起礹奉敕篆額

- 皇帝御極之十年,歲在癸未,制授通奉大夫前河南等處行中書省參知政事訥懷為集賢侍讀學士。越明年春,集賢學士脫憐等

- 言:“訥懷曾大父故順天路達魯花赤老索,當

- 太祖皇帝基命之際,奧有成績,列於功載,宜賜之碑銘,以寵示來裔。其令翰林學士歐陽玄為文,集賢侍講學士蘇天爵書,翰林學

- 士承旨張起礹篆額以賜。”

- 制曰:“可。”臣玄謹按事狀:老索,唐兀氏,世為寧夏人。幼穎悟,長以驍勇聞時。

- 太祖皇帝拓境四方,老索知天意所向,屢諷其國王失都兒忽率諸部降。

- 太祖皇帝素聞其名,及見,偉其材貌,俾入宿衛。老索昕夕唯謹,及遇攻討,被堅執銳,親冒矢石,為士卒先。

- 上益壯之,賜號“八都兒”。八都兒者,華言驍銳無敵也。妻以宮女康里真氏。從征諸部克大水濼,拔烏沙堡,又破桓、撫等州。及分□□□

- 河南武宣王察罕那顏麾下,敗金將完顏九斤、萬奴等軍數十萬於野狐嶺。還定雲內,西徇地至涼州諸郡。

- 太祖皇帝賜金符為統軍,及織紋數十匹,以旌其功。分討欽察、兀羅思、回回等國,推鋒破敵,所向無前。大軍至答也失的□□□號,

- 至險,老索乘勝驅衆涉之,□□平地,斡羅兒、孛哈里、薛迷思干等城皆堅壁,未易猝拔,竟一鼓克之。札剌蘭丁迷里彼驍□□□鐵

- 門閞,老索深入,身中流矢,勇氣彌厲,麾軍力戰,遂平之。

- 太宗皇帝南征,從下河中,定南京。甲午,金亡。詔採良家女以備後宮,諫曰:“中原甫定,宜收攬英雄,以開混一之業,今乃嬪……”

Right Side

- 大□賜曰 全□兩丙申(使?)□□…… 盛順天□汝南忠武王張公□□□老索協力屏翰(請?)□□□(六?)□□於……碑

- 燕南自為一路,民至今便之。(年?)一十即上惠(符?)乞□骨……

- 上優憐之,賜黃金五十兩,白金三百兩。中統建元六月二十三日薨於正寢,壽七十三。越明年某月日,葬於清苑縣太靜鄉之先塋。

- 康里追封夫人。子二人,長阿(勾)早亡。次忙古,起家為行軍千戶。丁巳,攻蜀,所至先登。己未,

- 憲宗圖合州釣魚山,克捷居多,□□常勝,遂沒於陣,贈至中大夫,僉太常禮儀院事。娶眭氏,子一人,忽都不花,德器溫厚,至元十七年,

- 擢奉議大夫、祁州達魯花赤。為政明恕,編氓以其有德,至今以顏子目之。秩滿

- 光獻翼聖皇后以其

- 先朝舊臣,諭都官不次擢用。時阿合馬柄政,官非賂莫進,忙古疑為忽都不花之誤。慨然曰:“為民父母,罄產鬻官,而復刻削於民以求利,可乎?”遂無仕進

- 意,移遂州達魯花赤。至元二十一年五月九日,卒於家,年三十有六。娶民氏,奉柩歸葬於清苑之先塋。子一人,即訥懷,父沒年甫三

- 歲,母民氏□□守義,育鞠有加。既長,從師問學,涉獵經史。入京,因司徒明里以見

- 仁宗皇帝於□□□□(使?)左□□授中書直省舍人沿榭護送趙王公□□,道塗禁戢其徒御,所過郡邑無擾,歸以能聲,

- 廟堂遷知安東□選□監察御使□□□曰:“汝父連收二州,雖獲廉而未嘗預清要之選,汝今得之宜效節以報國顯親□……”

- 尋拜河東廉訪使□□宣□,有世襲,知府怙寵不法,輒發其奸,獄成而逃,訴於朝

- 由……是

Left Side

- □□□□□登佚氏生□□鄙……葬於□□□南大同,魂無不之……

- □子有孫□□□忠順匯此慶澤,發於曾孫,曾孫勉……遭文

- □皇□□□謹(定?)令譽進登察(官?) 踐揚中朝……參預兩省……子

- 我皇□淵□寔□□輕……進(照?)生功顯爾,引下曾孫,有母實賢,秉節迪人,式隆其傳。

- □二業□□□□未表其進□□□□□自我(基?)命,(貞?)有諡,及告奉常,詞□臣……□苑之南賁爾貞域……之

- 銘……

- 聖世之德

- 至正十年四月吉日曾孫訥懷立石

- 保定儒士李肅、處士胡賓元摹

- □(玉)川、蔣伯從、劉弘毅、張寬刻

Translation

Front Side

Spirit-Way Stele Inscription¹ for Laosuo of Hexi,² the late Darughachi³ of Shuntian Route,⁴ bestowed by imperial command of the Great Yuan.

Text composed by imperial command by the Hanlin Academician Recipient of Edicts, Grand Master for Glorious Happiness and Drafter, concurrently Compiler of the Dynastic History, Ouyang Xuan (1283–1357).

Written down in red ink by imperial command by the Worthy Attendant, Expositor and Grand Master for Palace Attendance, concurrently Libationer of the National Academy, Su Tianjue (1294–1352).

Seal script heading written by imperial command by the Hanlin Academician Recipient of Edicts, Grand Master for Glorious Happiness and Drafter, concurrently Compiler of the Dynastic History, Zhang Qiyan (1285–1353).

In the 10th year after the accession of the Emperor [Shundi] (r. 1333–1370), in the cyclic year guiwei (Year of the Water Goat) [1343], Noqai, Grand Master for Thorough Service and previously Assistant Grand Councilor of the Branch Secretariat of Henan etc., was made a Worthy Attendant and Academician Reader.⁵ In the spring of the following year the Worthy Academician Tuolian and others said: "The great-grandfather of Noqai was Laosuo, the late Darughachi of Shuntian Route. At the time that Emperor Taizu [Genghis Khan] (r. 1206–1227) was establishing his mandate he had great achievements and was listed on the roll of honour. It is fitting to bestow a memorial inscription on him, in order to show favour to his descendants. It should be commanded that the Hanlin Academician Ouyang Xuan compose the text, the Worthy Attendant and Expositor Su Tianjue write it down, and the Hanlin Academician Recipient of Edicts Zhang Qiyan write the seal script heading. [The emperor's] edict said: "Permitted." I, [Ouyang] Xuan, carefully note the facts of his life:

Laosuo was a Tangut, and his family had lived in Ningxia for generations.⁶ When he was young he was intelligent, and when he grew up he was renowned for his courage. When Emperor Taizu was expanding his territory in all directions, Laosuo knew which side Heaven favoured, and several times admonished his king, Shidurghu (Emperor Xiangzong, r. 1206–1211), to lead his forces in surrender [to Genghis Khan].⁷ Emperor Taizu had long heard of his name, and when he saw him he thought that he had an impressive demeanour, and so had him join his bodyguard. Laosuo diligently [carried out his duties] from dawn to dusk. When it came to fighting the enemy he wore sturdy armour and carried a sharp blade, dodging arrows and missiles he led the troops from the front. The emperor considered him to be even stronger, and gave him the title Baghatur, which in Chinese means "brave and indefeatable".⁸ He gave a palace girl of the Zhen family of the Kankalis tribe to be his wife. He participated in campaigns against the various tribes, and [was in the army that] defeated the enemy at Big Water Lake and took Wusha Fort; they also captured Huanzhou, Fuzhou, and other places [in 1211]. He was put under the command of Chaghan Nayan,⁹ Prince Wuxuan of Henan, and they defeated an army of several hundred thousand commanded by the Jin generals Wanyan Jiujin and Wannu at Wild Fox Peak [in 1211]. On their way back they pacified Yunnei [in 1211], and campaigned westwards as far as Liangzhou and various provinces [of the Western Xia]. Emperor Taizu gave him the gold tally of an army commander, as well as several tens of bolts of cloth, in order to celebrate his success. He separately participated in campaigns against the countries of the Kypchaks, Russians and Persians. He charged into the enemy and no-one was ahead of him in battle. When the main army arrived at Dayeshi ... in great danger, Laosuo followed up the victory by chasing after them ... level ground. The cities of Otrar, Bukhara and Samarkand all had strong walls, and it should not have been easy to take them quickly, but unexpectedly they were captured with a single roll of the drums.¹⁰ ... the iron gates closed, and Laosuo went deep in. He was hit by a stray arrow, but his bravery was undiminished, and he led the army in battle, thereupon defeating [the enemy]. When Emperor Taizong went on a campaign to the south he accompanied him into the Hezhong region and pacified the Southern Capital (Kaifeng) [in 1232–1233]. In the cyclic year jiawu (Year of the Wooden Horse) [1234] the Jin state was overthrown, and [the emperor] ordered girls from good families to be selected for the inner palace. [Laosuo] remonstrated, saying: "The Central Plains have only just been pacified, so it is fitting to gather together heroes in order to establish an empire, but now it is concubines ..."

Right Side

[Emperor Taizu?] bestowed ... ounces of gold. In the cyclic year bingshen (Year of the Fire Monkey) [1236] ... Shuntian ... Prince Zhongwu of Runan, Lord Zhang,¹¹ ... Laosuo's assistance was a great help ... at ... stele. Yannan was created a Route in its own right, which the people up to now consider to be a beneficial. ... The emperor loved him dearly him, and bestowed upon him fifty ounces of gold and 300 ounces of silver. On the 23rd day of the 6th month of the 1st year of the Zhongtong era [1st August 1260] he died in his sleep. His age was seventy-three. On a certain day and month of the following year he was buried in the ancestral burial ground at Taijing District in Qingyuan County.¹² His Kankalis [wife] was retrospectively created a Lady. He had two sons, the eldest, Agou (?), who died young, and the second, Manggu, who left home to become a Battalion Commander in the army.¹³ In the cyclic year dingsi (Fire Snake) [1257] he attacked the region of Shu, and wherever he went he was always first into battle. In the cyclic year jiwei (Earth Goat) [1259] Emperor Xianzong (r. 1251-1259) tried to take Fishing Hill in Hezhou, and he had many victories ... was often victorious, but then he fell in battle. He was posthumously promoted to the position of Grand Master of the Palace serving in the Commission for Ritual Observances. He had married a lady of the Sui family, and had one son, Qutu-buqa, who was virtuous and amicable.¹⁴ In the 17th year of the Zhiyuan era [1280] he was given the position of Grand Master for Palace Counsel and Darughachi of Qizhou. In government he was enlightened and forgiving, and the registered populace thought he was virtuous. Up to today he is looked upon like [Confucius's disciple] Yan Hui. When his term of appointment was over, on account of his being an old minister at the previous court, Grand Empress Guangxian Yisheng (c. 1161–1230) told the Ministry of General Administraion to give him an extraordinary appointment.¹⁵ At that time Ahmad Fanākatī (d. 1282) was in power, and an official did not gain promotion without bribery. Manggu throught that [his son's lack of promotion] was Qutu-buqa's own fault.¹⁶ [Qutu-buqa] impassionately exclaimed: "Is it right for an official, as the parent of the people, to empty the coffers to buy an appointment, and furthermore to harshly treat the people in order to seek profit?" Thereafter he had no desire to progress in his official career. He moved to be Darughachi of Suizhou. On the 9th day of the 5th month of the 21st year of the Zhiyuan era [25th May 1284] he died at home. His age was thiry-six. He had married a lady of the Min family, and she took his coffin back to be buried in the ancestral burial ground in Qingyuan. He had one son, namely Noqai, who was just three years old when his father died. His mother, Madam Min ... remained a widow, living in increasingly straitened circumstances as she got older. When [Noqai] grew up, he studied under a teacher, and read a little of the Classics and Histories. He went to the capital, and through the minister Mingli¹⁷ he was able to have an audience with Emperor Renzong (r. 1311–1320) at ... left ... conferred on Yan Xie, Drafter of the Secretariat of the Metropolitan Area, the task of escorting Prince[ss] Zhao ... On the road carriage-bearers and riders were prohibited, and there were no disturbances at any of the places they went through.¹⁸ On his return he gained a reputation for being capable. At the imperial court he was promoted to Andong ..., selected ... Investigating Censor ... said: "Your father captured two cities in succession, and although he had a reputation for being honest (?) he never put himself forward for selection for a sinecure. Now that you have received one, it is appropriate that you do your utmost to repay your country in order to bring honour to your parents ..." ... went to pay his respects to the Investigation Commissioner of Hedong ... hereditary, the Prefect relied on the emperor's favours to break the law, and his treachery was often exposed, but he escaped prison and appealed to the court ...¹⁹

Left Side

[7 lines of a fragmentary poetic eulogy not translated.]

Memorial stone erected by [Laosuo's] great-grandson, Noqai, on an auspicious day of the 4th month of the 10th year of the Zhizheng era [7th May to 4th June 1350].

Text copied [in preparation for engraving] by the scholar Li Su and the recluse Hu Binyuan from Baoding.

Text engraved by Jiang Bocong, Liu Hongyi and Zhang Kuan from Yuchuan (?).

Notes

1. A Spirit-Way Stele Inscription is an epitaph inscribed on a stele that is erected at the site of someone's grave. This stele was presumably erected by Laosuo's grave. Liang Songtao suggests that this stele is a replacement for an earlier stele, with a recarved copy of the original inscription, but the basis for this theory is that the Baoding stele inscription was carved in 1360 (10th year of the Zhizheng era), but the inscription's authors Su Tianjue and Ouyang Xuan died in 1352 and 1357 respectively. However, Liang made a mistake with the dating as the 10th year of the Zhizheng era is actually 1350, so in my opinion there is no reason to suppose that this is not the original stele.

2. Hexi 河西 "West of the Yellow River" is the common name for the region where the Tangut people lived (modern Ningxia, Gansu and parts of Inner Mongolia).

3. A darughachi ᠳᠠᠷᠤᠭᠠᠴᠢ (transcribed in Chinese as dálǔhuāchì 達魯花赤) was an official appointed by the Mongols to supervise the local governance of cities, provinces, and auxiliary military commands in the lands that they had conquered, sometimes referred to as "governor" or "supervising governor" in English sources. They were responsible for overseeing such matters as census taking, tax collection, and military recruitment. In 1268 Kublai Khan removed all Jurchen, Khitan and Chinese Darughachi from their posts, but Persian, Uighur, Naiman and Tangut Darughaci kept their positions (Yuan History ch. 6), which shows that Tangut officials were more highly regarded than Jurchen, Khitan and Chinese officials.

4. Shuntian Route 順天路 was the name of the administrative region centred on Baoding city (previously called Baozhou 保州) from 1238 to 1275, when it was renamed Baoding Route 保定路. During the 12th month of the 1st year of the Zhenyou era (January/February 1214), the Mongols attacked and destroyed the city of Baozhou, massacring its inhabitants, numbering more than 90,000 households. After the Mongols had laid waste the city, it lay desolate and abandoned for nearly fifteen years, until 1227 when Genghis Khan appointed Zhang Rou 張柔 (1190–1268) as military commander of Shuntian Route.

5. Noqai ᠨᠣᠬᠠᠢ (transcribed in Chinese as nèhuái 訥懷) is a Mongolian name meaning "Dog". Laosuo's son, grandson and great-grandson all have Turkic-Mongolian names, and as Laosuo's wife was not a Tangut it is quite likely that Laosuo's immediate family and descendants did not speak the Tangut language.

6. Laosuo is evidently a Tangut name, although it is not included in the lists of Tangut family names given in Miscellaneous Characters (雜字) and Newly Collected Grains of Gold (碎金置掌文). It is perhaps a transcription of the otherwise unattested Tangut family name 𗒉𗦗 [la¹ so²] (see discussion in Marc Miyake, The Lost Laso).

7. Shidurghu ᠱᠢᠳᠤᠷᠭᠤ (transcribed in Chinese as shīdū'érhū 失都兒忽) was the name given to the last emperor of the Western Xia (Li Xian, r. 1226–1227) by the Mongols, and is a Mongolian word meaning "simple, right, just". In François Pétis de la Croix's 1710 Histoire du Grand Genghizcan (translated into English in 1722 as The History of Genghizcan the Great), which was based on Turkish sources, his name is given as Schidascou. However, in this case it cannot be the last emperor as Laosuo has defected to the Mongols by 1211, and so Shidurghu must here refer to Emperor Xiangzong (r. 1206-1211), who was emperor during the Genghis Khan's first war against the Western Xia. It has been suggested that Shidurghu was a title applied to any Tangut emperor, not specifically the last emperor, but given what it means in Mongolian this would seem unlikely, and I think that the use of Shidurghu here is simply a mistake.

8. Baghatur or Ba'atur ᠪᠠᠭᠠᠲᠤᠷ (transcribed in Chinese as bādū'ér 八都兒) is a Mongolian word meaning "hero" or "brave, courageous", and was frequently granted as an honorific title by Mongol rulers.

9. Chaghan Nayan ᠴᠠᠭᠠᠨ ᠨᠠᠶᠠᠨ ("white eighty") refers to the Tangut general Chaghan, the son of a Western Xia minister who followed Genghis Khan at a young age, rising to become the highest-ranking Tangut military official in the Mongol army.

10. The cities of Otrar, Bukhara and Samarkand were taken by the Mongols during the invason of Khwarezmia in 1219–1220.

11. Prince Zhongwu of Runan is Zhang Rou 張柔 (1190–1268), military governor of Baoding, who rebuilt the city after it had been devestated during the war against the Jin. He was originally a military official under the Jin, but he surrendered to the Mongols in 1218.

12. Qingyuan County 清苑縣 was the county covering Baoding city.

13. Manggu (transcribed in Chinese as mánggǔ 忙古) is a Turkic name meaning "Eternal" (corresponding to Mongolian möngke ᠮᠥᠩᠬᠡ).

14. Qutu-buqa ᠬᠤᠲᠤ ᠪᠤᠬᠠ (transcribed in Chinese as hūdū bùhuā 忽都不花) is a Mongolian name. The first element corresponds to Mongolian ᠬᠤᠲᠤᠭ qutuɣ, meaning "blessing, bliss, benediction, happiness". The second element corresponds to Mongolian ᠪᠤᠬᠠ buqa, meaning "ox, bull".

15. The sentence starting "When his term of appointment ..." can only refer to Laosuo, as the Grand Empress Guangxian Yisheng (wife of Genghis Khan) died in about 1230, but in that case the sentence is out of place.

16. This sentence makes no sense to me, as Manggu apparently died in battle in 1259, when his son was only about ten years old.

17. Mingli is perhaps Mingli Donga 明里董阿 (d. 1340), who was the head of the Bureau of Imperial Manufacture (see James C. Y. Watt, When Silk was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997) p. 96). "Minister" (Chinese Situ 司徒) is here a courtesy title rather than the title of an actual position. His name is Turkic, meaning "Tiger with a birthmark" (mäŋlig toŋa).

18. It is not clear to me what role Yan Xie has in the mission to escort Princess Zhao on her journey, as it seems to be Noqai who gets the credit for a job well done. Nor do I understand the statement that "On the road carriage-bearers and riders were prohibited".

19. I do not know who the last sentence on the right side of the stele is talking about, and how this relates to Noqai.

Family Tree of Laosuo

| Laosuo 老索 (1188–1260) |

Madam Zhen 真氏 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Agou 阿勾 |

Manggu 忙古 (?–1259) |

Madam Sui 眭氏 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Qutu-buqa 忽都不花 (1249–1284) |

Madam Min 民氏 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Noqai 訥懷 (1282–) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tangut Monks in Baoding and Beyond

Laosuo and his family were not the only Tanguts living in Baoding during the Yuan dynasty. Standing next to the Stele of Laosuo in the Ancient Lotus Pond are two dharani pillars with Buddhist inscriptions in Tangut script which were discovered in 1962 on the site of a Buddhist temple in the village of Hanzhuang 韓莊 in the northern suburbs of Baoding (see Tangut dharani pillars on Wikipedia for more information).

Tangut Dharani Pillars in Baoding

These two pillars were erected during the middle of the Ming dynasty, in the 15th year of the Hongzhi era (1502) by Trashi Rinchen བཀྲ་ཤིས་རིན་ཅན་, the Tibetan abbot of the Temple for Promoting Goodness (Xingshan Temple 興善寺), in memory of two monks who had recently died, at least one of whom had a Tangut name. Clearly this was a Tibetan Buddhist temple with a mixture of Tibetan and Tangut monks (Tanguts being adherents of Tibetan Buddhism). The Tangut text on the pillars lists the names of some eighty benefactors who donated money for their erection, and even though they may not all have been Tanguts, it suggests that there was a relatively large community of Tangut inhabitants in Baoding during the early Ming dynasty—and probably an even larger Tangut community during the Yuan dynasty. The temple was perhaps founded (or re-founded) in response to the settlement in Baoding of Laosuo and Tangut members of his household, as well as other Tangut soldiers and officials in the occupying Mongol forces.

Xingshan Temple was destroyed during the first half of the 20th century, but it originally had a stupa-shaped white pagoda, similar to the Yuan Dynasty white dagoba at Miaoying Temple in Beijing. Miaoying Temple was rebuilt and dedicated to Tibetan Buddhism during the early Yuan dynasty following the adoption of Tibetan Buddhism by Kublai Khan; and like Xingshan Temple there is evidence that the temple housed Tangut monks as well as Tibetan monks. In 1900, during the chaos of the Boxer Rebellion, Georges Morisse (an interpreter at the French Legation in Beijing) and M. Berteaux (an interpreter at the French Legation in Korea) found six discarded volumes of the Tangut translation of the Lotus Sutra (Saddharma Puṇḍarīka) in a pile next to the White Stupa of Miaoying Temple. The presence of Tangut books in the temple surely indicates that there would once have been Tangut monks at the temple.

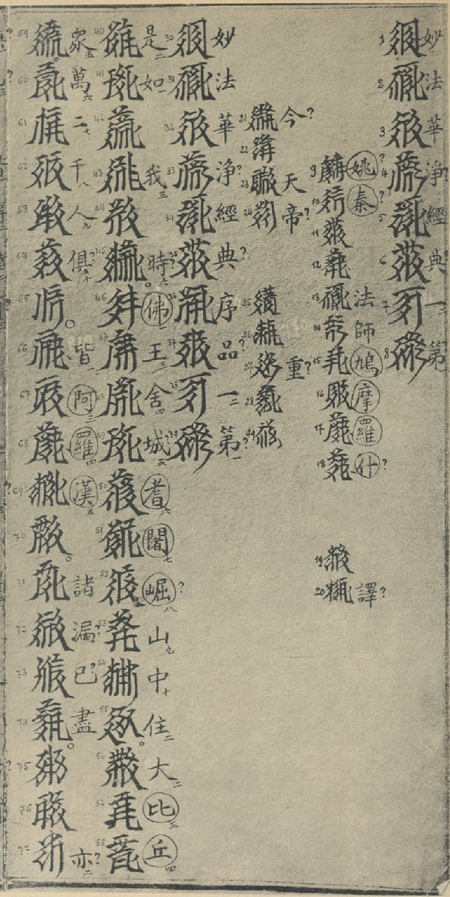

Annotated copy of a page of the Tangut Lotus Sutra from Miaoying Temple

G. Morisse, "Contribution préliminaire à l'étude de l'écriture et de la langue si-hia" (1904)

Another Tibetan Buddhist temple founded during the Yuan dynasty was the Yongming Baoxiang Temple (永明寶相寺), situated at the Juyongguan Pass northwest of the capital, Dadu (modern Beijing), on the road from the capital to the summer capital, Shangdu. In 1342–1345 an archway surmounted by three white stupas was built at the entrance to the temple by command of the last Yuan emperor. The inside of the archway is engraved with two dharani-sutras (one of which is the same as that engraved on the Baoding dharani pillars), in six different scripts including Tangut. It is therefore possible that the Yongming Baoxiang Temple also housed Tangut monks.

That Tangut was chosen for an imperially-commissioned monument also indicates the important position of Tangut monks under the Yuan dynasty. The widespread presence of Tangut monks in China during the Yuan dynasty is further indicated by the Yuan History, which explicitly mentions "monks from Hexi" no fewer than six times, all in connection with taxation regulations. For example, in 1282 it is recorded that an edict was issued to the effect that Buddhist, Daoist and Christian monks from Hexi who are married with a family should pay tax the same as common people (Yuan History ch. 12).

Last modified: 2020-02-06.

History | Inscribed Stones | Tangut

Index of BabelStone Blog Posts