BabelStone Blog

Friday, 3 July 2015

Ode to the Tangut Tripitaka : Part 1

Acknowledgements

This two-part post is based on a presentation I gave for the Tangut workshop at Cambridge University in September 2014. I would like to express my gratitude to Imre Galambos for organizing the event, and for the helpful comments and suggestions made by Imre, Nathan Hill, Guillaume Jacques and the other participants that enabled me to develop the talk into its current form. I would also like to thank Viacheslav Zaytsev for providing me with invaluable material relating to Tangut Buddhist literature, without which I could not have written this post.

Tangut Buddhist Texts

The collection of Tangut texts recovered from the Western Xia fortress city of Khara-Khoto by P. K. Kozlov in 1908–1909, and now held at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts [IOM] of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg, includes a very large number of Buddhist texts, both manuscripts and printed editions (see E. I. Kychanov's 1999 Catalogue of Tangut Buddhist Monuments at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences). The most well-represented text amongst this collection is the Tangut translation from Chinese of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra "Great Perfection of Wisdom Sutra" [GPWS] (Chinese Dà bōrě bōluómìduō jīng 大般若波羅密多經典; Tangut le pa zha po lo bi ton lwyr rer 𘜶𘄒𘎑𘏞𗓽𗕥𗸰𗖰𗚩). GPWS is a huge compendium of Perfection of Wisdom texts in 600 chapters, reputedly translated into Chinese by the famous Tang dynasty monk Xuanzang 玄奘 (c. 602–664) and his disciples. The IOM collection includes eleven copies or partial copies of Tangut manuscript versions of chs. 1–400, as well as a single manuscript scroll covering chs. 401–450. No Tangut translations of chs. 451–600 are known, and no printed editions of the text are known. The manuscripts covering chs. 1–400 are of two formats:

- Pothi-format manuscripts, written on both sides of oblong sheets of paper that mimic the shape of Indian palm leaf manuscripts [IOM Tang. 334 Nos. 9–15];

- Concertina-format manuscripts, written on one side of sheets of paper folded and pasted together to form concertina-like scrolls that can be stored in cases [IOM Tang. 334 Nos. 16–19].

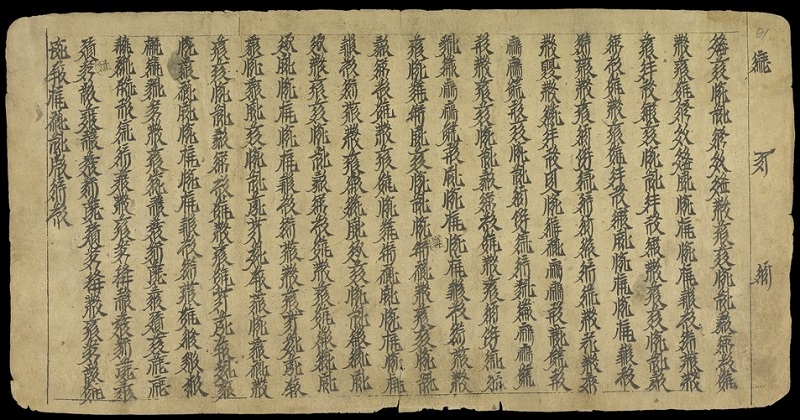

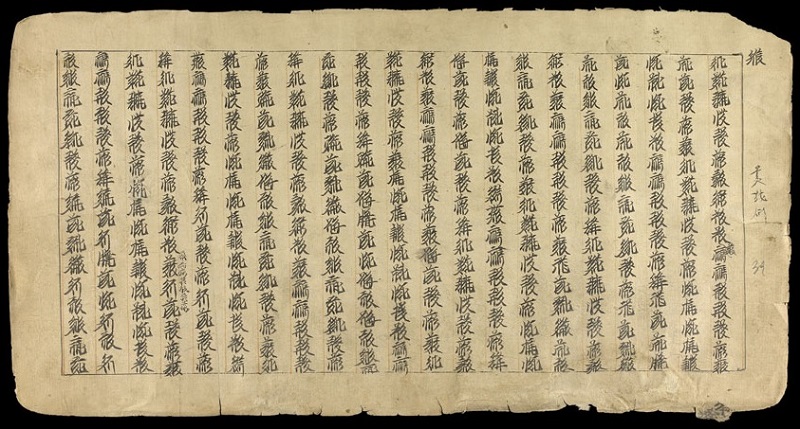

The pothi-format manuscripts are divided into bundles of about 100–120 double-sided sheets covering exactly ten chapters of the text. Each ten-chapter section is paginated along the right edge of one side of the sheet, usually with the relative chapter number ("1" through "10" in Tangut script) followed by the sheet number within the chapter (see Fig. 1), but sometimes numbered sequentially across the ten chapters (see Fig. 2), and occasionally paginated using a combination of these two numbering systems. Regardless of the system of pagination, the pagination is always preceded by a Tangut index character (index characters for Tangut Buddhist texts are briefly discussed in Kychanov 1999 pp. 12–13). The same index character is used across all sheets of a ten-chapter section, but a different index character is used for each ten-chapter section. This Tangut character serves to uniquely identify which ten-chapter section of the 600-chapter text any particular sheet comes from. For example, in Fig. 1 the index character is at the top right of the sheet, below which is the number 'one' in Tangut followed by the number 'four' in Tangut, indicating that it is the fourth sheet of the first chapter of the ten-chapter section of the sutra corresponding to this particular index character (in this case, chs. 61–70).

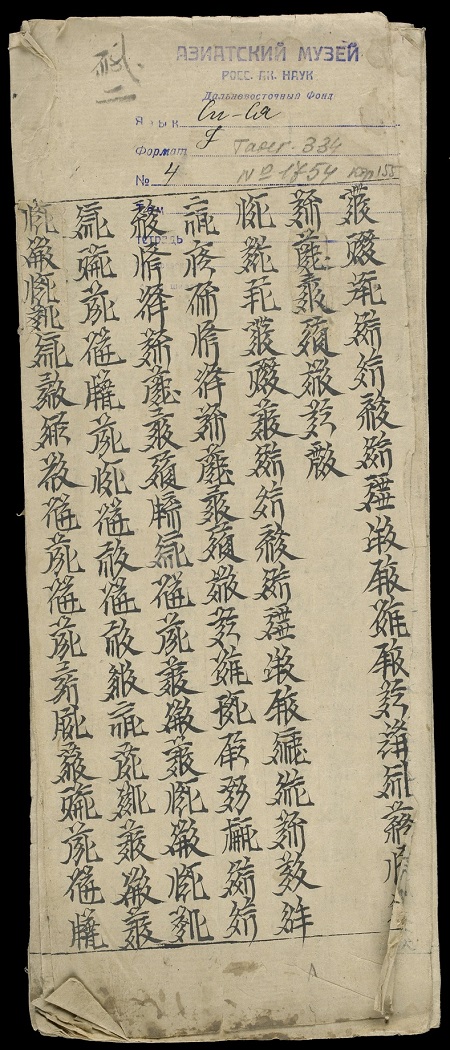

Fig. 1: Sheet 1.4 from chs. 61–70 of a pothi manuscript of GPWS [Tang. 334/249]

Sheets numbered sequentially by chapter, with the index character 𗩾 followed by relative chapter number 𘈩 ("1" = ch. 61) and sheet number within the chapter 𗥃 ("4") on the right edge of the sheet

Fig. 2: Sheet 76 from chs. 261–270 of a pothi manuscript of GPWS [Tang. 334/263]

Sheets numbered sequentially across ten chapters, with the index character 𗋚 followed by sheet number 𗒹𗰗𗤁 ("76") in cursive Tangut characters on the right edge of the sheet

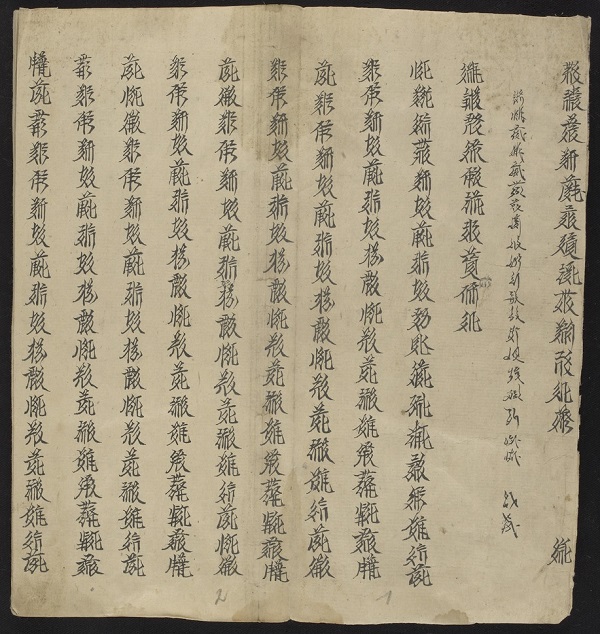

The concertina-format manuscripts are divided into individual chapters, with each chapter comprising a single fascicle, sometimes enclosed in a case. The concertina sheets are not paginated, but in most cases an index character is present after the chapter-initial and/or chapter-final title (see Figs. 3 and 4). The index character under the title is the same across each set of ten chapters, and is the same character found in the pagination of the corresponding chapters of the pothi-format manuscripts. However, the index character is not consistently present in the concertina versions, and on some chapters neither the chapter-initial nor chapter-final title are followed by an index character.

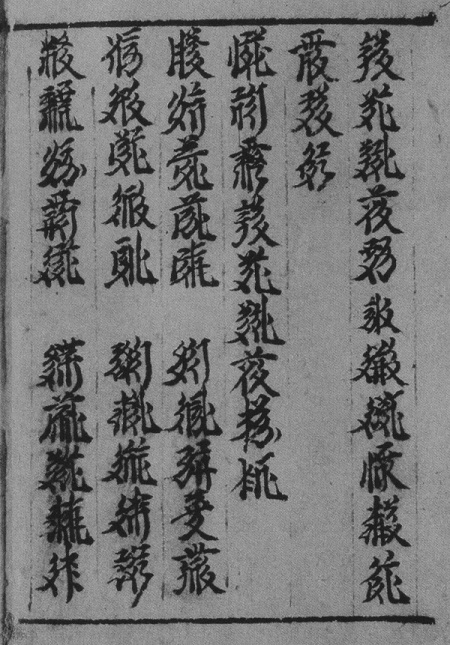

Fig. 3: First sheet of ch. 19 of a concertina manuscript of GPWS [Tang. 334/151]

Index character 𗿀 placed after a space following the initial title (character at the bottom right)

Fig. 4: Last sheet of ch. 19 of a concertina manuscript of GPWS [Tang. 334/151]

Index character 𗿀 placed after a space following the final title (character at the bottom left)

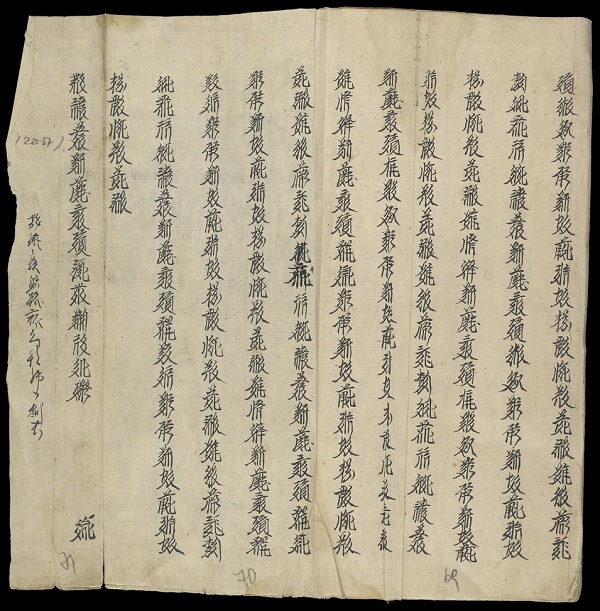

In one concertina version of GPWS (Kychanov 1999 No. 15), as well as occurring underneath the title, the index character is written in the upper margin of the first or last page of the manuscript, together with the relative chapter number written in Chinese (see Fig. 5). In another concertina version (Kychanov 1999 No. 10) the index character and relative chapter number are sometimes written in Tangut on the front cover for the chapter (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 5: First sheet of ch. 162 of a concertina manuscript of GPWS [Tang. 334/538]

Index character 𗳄 with relative chapter number in Chinese 二 ("2" = ch. 162) in top margin

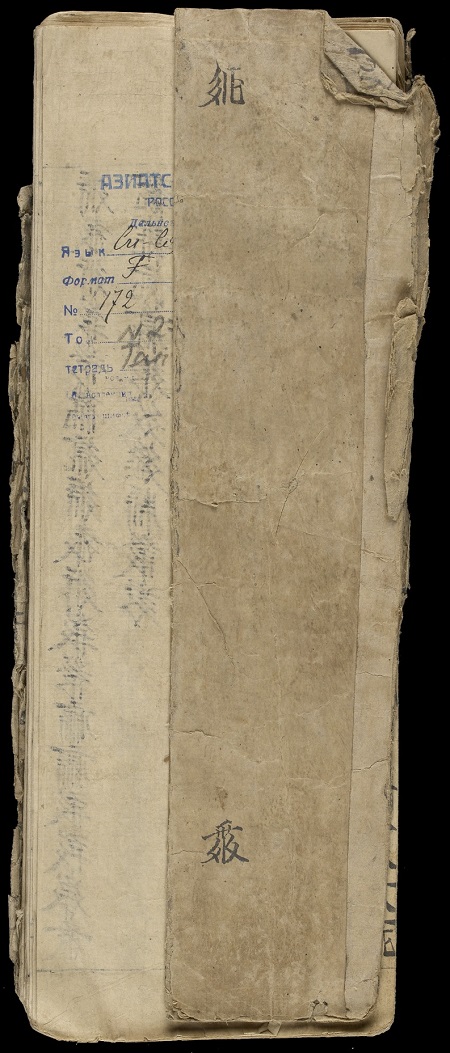

Fig. 6: Front cover of ch. 119 of a concertina manuscript of GPWS [Tang. 334/483]

Relative chapter number 𗢭 ("9" = ch. 119) at the top, and index character 𗴵 at the bottom of the cover

The use of index characters is most noticeable in the Tangut manuscripts of GPWS, but is not restricted to this one particular text. At least seventeen other Tangut Buddhist texts, mostly manuscripts but including five xylograph editions, record index characters after the chapter-initial or chapter-final title, or on their cover or wrapping (see Fig. 7). The titles of these eighteen texts are given in Table 1. I hope to be able to expand this table with more examples of Tangut Buddhist texts with index characters in the future.

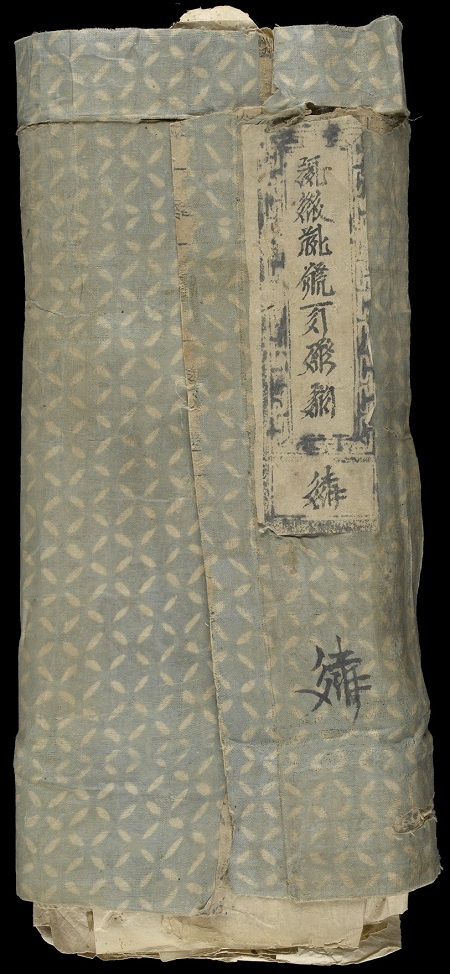

Fig. 7: Sutra wrapper for Jīnglǜ yìxiāng used to wrap ch. 271 of a concertina manuscript of GPWS [Tang. 334/433]

Index character 𗤳 at the bottom of the title label and below that on the silk wrapper

Table 1: Tangut translations of Buddhist texts with index characters

| Taishō No. | Title in Tangut, Chinese and Sanskrit or English | Size / Format | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 64 |

𗢳𘎪𗳻𗣧𘜉𗴼𗖰𗚩 tha tshe cha pho phi khew lwyr rer 《瞻婆比丘經》 Fóshuō zhānpó bǐqiū jīng Campā-bhikṣu-sūtra |

1 ch. ms. (concertina) |

Kychanov 1999 No. 3 Grinstead 1971 pp. 1229–1230 |

| 157 |

𗈁𗤻𗖰𗚩 vu va lwyr rer 《悲華經》 Bēihuá jīng Karuṇā-puṇḍarīka-sūtra Compassionate Flower Sutra |

10 chs. xylograph |

Nishida 1977 No. 32 Grinstead 1971 pp. 1–15 |

| 201 |

𘜶𗡮𘆡𗰜𗴺𘐳𗖰𗚩 le shwo tshe myr ma [?] lwyr rer 《大莊嚴論經》 Dà zhuāngyánlùn jīng Sūtrā-laṁkāra-śāstra |

15 chs. ms. (concertina) |

Kychanov 1999 No. 7 Grinstead 1971 pp. 1231–1239 |

| 220 |

𘜶𘄒𘎑𘏞𗓽𗕥𗸰𗖰𗚩 le pa zha po lo dzu ton lwyr rer 《大般若波羅蜜多經》 Dà bōrě bōluómìduō jīng Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra Great Perfection of Wisdom Sutra |

400 chs. mss. (concertina and pothi) |

Kychanov 1999 Nos. 9–19 Grinstead 1971 pp. 16–229, 1240–1256 |

| 262 |

𗤓𗹙𗤻𗑗𗖰𗚩 tho tsir va se lwyr rer 《妙法蓮華經》 Miàofǎ liánhuá jīng Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-sūtra Lotus Sutra |

8 chs. ms. and xylograph (concertina) |

Kychanov 1999 Nos. 78–80 Grinstead 1971 pp. 238–257, 1502–1521 |

| 279 |

𘜶𗣼𗾟𗢳𗤻𗡮𗖰𗚩 le chha va tha va shwo lwyr rer 《大方廣佛華嚴經》 Dà fāngguǎng fó huáyán jīng Mahā-vaipulya-buddhāvataṃsaka-sūtra Flower Garland Sutra |

80 chs. mss. (concertina and pothi) |

Kychanov 1999 Nos. 84–90 Grinstead 1971 pp. 258–888, 1507–1624 |

| 293 |

𘜶𗣼𗾟𗢳𗤻𗡮𗖰𗚩𗫡𗾈𘝦𘓞𘄿 le chha va tha va shwo lwyr rer ny mi jy ti te 《大方廣佛華嚴經》 (入不思議解脫境界普賢行願品) Dà fāngguǎng fó huáyán jīng Mahā-vaipulya-buddhāvataṃsaka-sūtra Flower Garland Sutra |

40 chs. xylograph |

Kychanov 1999 Nos. 92–96 Grinstead 1971 pp. 1625–1729 |

| 310 |

𘜶𘏨𗉋𗖰𗚩 le ly chon lwyr rer 《大寶積經》 Dà bǎojī jīng Mahāratnakūṭa-sūtra |

120 chs. mss. (concertina and pothi) |

Kychanov 1999 Nos. 97–102 Grinstead 1971 pp. 1730–1913 |

| 374 |

𘜶𘄒𘈬𗦺𗖰𗚩 le pa de phan lwyr rer 《大般涅槃經》 Dà bānnièpán jīng Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra |

40 chs. mss. (scroll, concertina and pothi) |

Kychanov 1999 Nos. 110–117 Grinstead 1971 pp. 1914–1995 |

| 439 |

𗢳𘎪𗱕𗢳𗖰𗚩 tha tshe rur tha lwyr rer 《佛説諸佛經》 Fóshuō zhūfó jīng Sarvabuddhaka |

1 ch. ms. (concertina) |

Kychanov 1999 No. 119 Grinstead 1971 p. 1996 |

| 446 |

𗋚𗦎𗵽𘆡𗑱𗡞𗢳𗦻𗖰𗚩 vy rar lu tshe ka tu tha me lwyr rer 《過去莊嚴劫千佛名經》 Guòqù zhuāngyánjié qiānfómíng jīng Buddhanāma (first of three parts) |

1 ch. ms. |

Nishida 1977 No. 160 Grinstead 1971 pp. 889–906 |

| 660 |

𗢳𘎪𘏨𗼮𗖰𗚩 tha tshe ly dzu lwyr rer 《佛説寶雨經》 Fóshuō bǎoyǔ jīng Ratnamegha-sūtra |

10 chs. ms. (concertina) |

Kychanov 1999 No. 165 Grinstead 1971 pp. 2053–2057 |

| 721 |

𗣼𗹙𗆫𗫻𗖰𗚩 chha tsir lyr je lwyr rer 《正法念處經》 Zhèngfǎ niànchǔ jīng |

70 chs. xylograph |

|

| 1453 |

𗰜𗺉𗄑𗄑𘟣𘎪𗴮𘊝𘈩𗡝𘉒 myr chhi ngorn ngorn du tshe de ir lew ka mo 《根本説一切有部百一羯磨》 Gēnběn shuō yīqiē yǒubù bǎiyī jiémó Mūla-sarvāstivāda-ekaśatakarma |

10 chs. ms. (concertina) |

Kychanov 1999 No. 289 Grinstead 1971 pp. 2208–2218 |

| 1509 |

𘜶𘄡𗌗𗰜𗴺 le se gu myr ma 《大智度論》 Dà zhì dù lùn Mahāprajñāpāramitopadeśa |

100 chs. xylograph |

Kychanov 1999 No. 290 Grinstead 1971 pp. 1224–1225 |

| 1562 |

𗠝𗁡𗣩𘉒𗣼𗧘𗑠𗖵𗰜𗴺 a phi tha mo chha vo rir bu myr ma 《阿毘達磨順正理論》 Āpí dámó shùnzhèng lǐlùn Abhidharma-nyāyānusāra |

80 chs. ms. (concertina) |

Kychanov 1999 No. 291 Grinstead 1971 pp. 1053–1069 |

| 1605 |

𘜶𗒛𗠝𗁡𗣩𘉒𗰖𗰜𗴺 le u a phi tha mo sho myr ma 《大乘阿毘達磨集論》 Dàchéng āpí dámó jílùn Abhidharma-samuccaya |

7 chs. ms. |

Nishida 1977 No. 163 Grinstead 1971 pp. 2219–2221 |

| 2121 |

𗖰𗩗𘁟𘍦 lwyr dzen do e 《經律異相》 Jīnglǜ yìxiāng Different Aspects of the Sutras and Vinaya |

50 chs. |

Nishida 1977 No. 163 |

Thousand Character Indexing of the Buddhist Canon

The use of index characters in these Tangut Buddhist texts parallels the usage of the characters of the Chinese Qiānzìwén 千字文 [QZW] "Thousand character text" to index the texts of the Chinese Buddhist canon. QZW is an elementary text comprising a thousand Han characters which was composed during the 6th century. As each character in the text only occurs a single time, it was ideally suited for indexing purposes, and from an early date it was used for indexing or cataloguing books and objects (see Wilkinson 2013 p. 601). Most notably, from the early Tang dynasty QZW was used to index the Buddhist canon, as recorded in Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù 開元釋教錄 "Kaiyuan Era Record of Buddhist Teachings" [Taishō Tripitaka No. 2154], a catalogue of Buddhist texts compiled by the monk Zhisheng 智昇 in the 18th year of the Kaiyuan era (730 CE). This is a huge work, divided into 20 rolls (juàn 卷), and the Taishō Tripitaka version lists some 9,078 Buddhist texts, amounting to around 27,869 rolls, and representing some 3,733 individual titles (with many duplicates, including six copies of itself).

The surviving editions of Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù do not record QZW index characters, but index characters are included in Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù Lüèchū 開元釋教錄略出 [KSL] "Abridged Kaiyuan Era Record of Buddhist Teachings" [Taishō Tripitaka No. 2155], a somewhat later and significantly shorter catalogue of Buddhist texts, comprising 4 rolls plus an appendix. Despite its title, and the fact that it still credits Zhisheng as its compiler, KSL is not exactly an abridgement of Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù. Rather, it seems to have been a completely new catalogue, influenced by the earlier Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù but listing a far reduced number of texts, with very few duplicate titles, which are ordered differently. The first four rolls of KSL list 1,080 texts in about 5,062 rolls, which are physically divided into 479 cases (zhì 帙). Each case usually contains about 10 rolls, and so large texts may fill several cases, whereas many short texts may be put together in a single case. The fact that the catalogue explicitly lists the physical distribution of texts into cases suggests that it may be a catalogue of the contents of a particular monastic library, not just a generic catalogue of Buddhist texts, in which case KSL can be seen as an abridgement of Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù that has been modified to reflect the actual contents of a particular library. The contents of KSL are listed here.

The distinctive feature of KSL is that each of the 479 cases is associated sequentially with one of the first 479 characters (from tiān 天 through qún 群) from QZW. This system of indexing Buddhist texts with the QZW is not found in extant editions of the earlier Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù, and as KSL includes Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù in its list of texts indexed using QZW (nos. 456–457, shēng 笙 and shēng 升), it is probable that the system of indexing using QZW characters was devised by the unknown compiler of KSL.

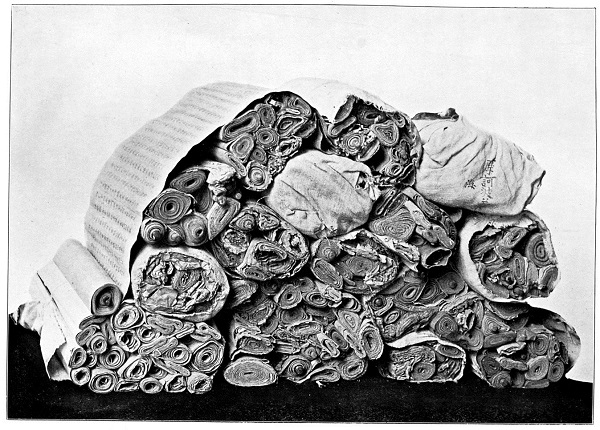

Fig. 8: Index character hǎi 海 on a bundle of scrolls from Dunhuang Cave 17

Aurel Stein, Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal Narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China (London, 1912) Plate 194

That this system of indexing Buddhist texts was actually used in monastic libraries, and was not just a cataloguer's affectation, is evidenced by some of the Chinese Buddhist texts retrieved from the sealed library of Cave 17 at the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang (see Rong 1999 pp. 251–252; Whitfield and Farrer 1990 p. 118; and Whitfield 2002 p. 327). A photograph by Aurel Stein of bundles of manuscript scrolls from Cave 17 (see Fig. 8) clearly shows the character hǎi 海 written next to the half-visible title of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra (Māhē bōrě bōluómì jīng 摩訶般若波羅蜜經) [Taishō Tripitaka No. 223] on the rough cloth wrapping of a bundle of scrolls. This accords with KSL, which records the characters jiāng 薑, hǎi 海 and xián 鹹 (64th, 65th and 66th characters of QZW) against the Mahāprajñāpāramitā-sūtra. That the same character is used for the same text in both KSL and in the sealed library of Cave 17 suggests that the specific indexing system used in KSL may have been widely adopted by monastic libraries across China. Unfortunately wrapping cloths such as those shown in this photograph, as well as fine silk sutra wrappers, have generally been separated from the texts they contained, so it is no longer an easy task to correlate the index characters on the wrapping cloths or wrappers now held by the British Museum with the Buddhist texts now held in the British Library (Stein 1921 Plate CVI and Whitfield and Farrer 1990 fig. 91 show a silk wrapper from Cave 17 with the character kāi 開 "open" stamped on both sides, but as kāi does not occur in QZW this may be an instruction on where to open the wrapper rather than an index character).

Sixteen of the seventeen Tangut texts with index characters listed in Table 1 correspond to texts included in KSL, as shown in Table 2. The only text not included is Fóshuō zhūfó jīng, which was written during the Song dynasty, several centuries after KSL was compiled.

Table 2: Correspondence between Tangut texts with index characters and KSL

| Taishō No. | Chinese Title | Physical extent in KSL | QZW Characters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 220 | 《大般若波羅蜜多經》 | 600 rolls in 60 cases |

1–60 天 through 柰 |

| 310 | 《大寶積經》 | 120 rolls in 12 cases |

73–84 龍, 師, 火, 帝, 鳥, 官, 人, 皇, 始, 制, 文, 字 |

| 293 | 《大方廣佛華嚴經》 | 50 rolls in 5 cases |

105–109 坐, 朝, 問, 道, 垂 |

| 279 | 《大方廣佛華嚴經》 | 80 rolls in 8 cases |

110–117 拱, 平, 章, 愛, 育, 黎, 首, 臣 |

| 374 | 《大般涅槃經》 | 40 rolls in 4 cases |

122–125 邇, 壹, 體, 率 |

| 262 | 《妙法蓮華經》 | 7 rolls in 1 case with three other titles 8 rolls in 1 case with one other title |

130 鳳 |

| 157 | 《悲華經》 | 10 rolls in 1 case |

135 食 |

| 660 | 《佛説寶雨經》 | 10 rolls in 1 case |

139 草 |

| 446 | 《三劫三千佛名經》 (《過去莊嚴劫千佛名經》, 《現在賢劫千佛名經》, 《未來星宿劫千佛名經》) | 15 rolls in 2 cases with one other title |

183–184 己, 長 |

| 1509 | 《大智度論》 | 100 rolls in 10 cases |

208–217 聖, 德, 建, 名, 立, 形, 端, 表, 正, 空 |

| 1605 | 《大乘阿毘達磨集論》 | 7 rolls in 1 case with three other titles |

235 非 |

| 201 | 《大莊嚴論經》 | 15 rolls in two cases with two other titles |

244–245 君, 曰 |

| 64 | 《瞻婆比丘經》 | 1 roll in 1 case with 29 other titles |

282 止 |

| 721 | 《正法念處經》 | 70 rolls in 7 cases |

289–295 篤, 初, 誠, 美, 慎, 終, 宜 |

| 1453 | 《根本説一切有部百一羯磨》 | 10 rolls in one case |

339 傅 |

| 1562 | 《阿毘達磨順正理論》 | 80 rolls in 80 cases |

397–404 逐, 物, 意, 移, 堅, 持, 雅, 操 |

| 2121 | 《經律異相》 | 50 rolls in 5 cases |

440–444 靈, 丙, 舍, 傍, 啟 |

Based on the correspondence between Tangut texts with index characters and texts listed in KSL, it seems probable that all of the Buddhist texts listed in KSL that were translated into Tangut were assigned sequential index characters in the same way that the corresponding Chinese texts were. That the index characters are found in a wide variety of manuscript and xylograph texts indicates that the index characters were not an ad hoc system applied haphazardly to individual texts by individual scribes, but must represent a unified system that was applied consistently at different times and places to the texts of the Tangut Buddhist canon. We can assume that there must have been a catalogue of Tangut Buddhist texts which recorded which index characters referred to which particular texts, similar in scope to KSL. Although this text has not survived, we can attempt to reconstruct parts of the Tangut version of the Thousand Character Text used to index the Tangut Buddhist canon from those Tangut texts which record index characters.

Index Characters in Tangut Buddhist Texts

The tables below list all the index characters from the Tangut texts listed in Table 1 that I have been able to identify, ordered according to the sequence of the corresponding QZW character in KSL. Where possible I include in the "Example" column a link to an example of a text showing the particular index character, from one or more of the following sources. Where a text occurs in different formats (e.g. pothi and concertina formats of GPWS), I try to provide one example for each format.

- Endangered Archives Programme [EAP] digitization of Tangut texts collected by Pyotr Kozlov from Khara-Khoto that are held at the IOM in Saint Petersburg (pressmarks starting "Tang.");

- International Dunhuang Project [IDP] digitization of Tangut texts collected by Aurel Stein from Khara-Khoto that are held at the British Library in London (pressmarks starting "Or.12380");

- XIXIA Documents from Dunhuang in the Bibliothéque nationale de France [法藏敦煌西夏文文獻] (2007) (pressmarks starting "Pelliot");

- Grinstead's Tangut Tripiṭaka [TT] (1971).

Kychanov 1999 pp. 690–691 lists the index characters used for six texts in the catalogue, and the existence of index characters is noted in the catalogue entries for some other texts. These do not entirely correspond with my own observations, and where there are differences between my reading and the character given in Kychanov 1999, both characters are given in the table for reference. If I have been unable to find an example of an index character in the texts available to me but it is listed in Kychanov 1999 then I note the Kychanov reference under "Example"—in these cases I am not yet able to confirm the correctness of Kychanov's reading.

The index characters are sometimes written incorrectly in the manuscript texts, especially in the pothi versions. For example, in the pothi version of GPWS chs. 51–60 the character 𗾟 (L3310) "vast" is sometimes written so it looks more like 𗼍 (L3435) "sage"; and in the pothi version of GPWS chs. 91–100 the character 𗈐 (L0944) "not" is usually written so it looks more like 𗓰 (L4693) "deep". Even xylograph editions are not always correct, and for example in the xylograph edition of the Lotus Sutra the index character 𗿸 (L3703) "title" is written with the vertical line in the wrong position. In cases such as these the incorrect character form has been silently corrected to its standard form.

Table 3.1: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 220 (大般若波羅蜜多經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 1 | 𘀗 | L3950 | ¹tshwu₄ | heaven, sky | Tang. 334/134 (chs. 1–10) Tang. 334/140 (ch. 10) |

| 11–20 | 2 | 𗿀 | L2107 | ¹tsir₁ | earth | Tang. 334/135 (chs. 11–20) Tang. 334/154 (ch. 13) |

| 21–30 | 3 | 𗅋 | L1918 | ¹mi₄ | not | Tang. 334/136 (chs. 21–30) Tang. 334/155 (ch. 30) |

| 31–40 | 4 | 𗪜 | L2479 | ¹nor'₄ | origin, source | Tang. 334/137 (chs. 31–40) Tang. 334/191 (ch. 31) |

| 𗪾 | L2668 | ¹kuq₁ | loose | Kychanov 1999 p. 690 | ||

| 41–50 | 5 | 𗲠 | L1364 | ¹nga₁ | void, emptiness | Tang. 334/138 (chs. 41–50) Tang. 334/156 (ch. 48) Or. 12380/2053 (ch. 49) |

| 51–60 | 6 | 𗾟 | L3310 | ²vaq₁ | vast, wide | Tang. 334/248 (chs. 51–60) |

| 61–70 | 7 | 𗩾 | L2091 | ²zi₄ | extreme | Tang. 334/249 (chs. 61–70) Tang. 334/187 (ch. 68) |

| 71–80 | 8 | 𗠁 | L0206 | ²bu'₁ | victory | Tang. 334/247 (ch. 80?) Tang. 334/422 (ch. 72) |

| 81–90 | 9 | 𗬗 | L2039 | ²vi₁ | land, soil | Tang. 334/247 (chs. 81–90) Tang. 334/471 (ch. 81) |

| 91–100 | 10 | 𗈐 | L0944 | ¹myq₁ | not | Tang. 334/355 (chs. 91–100) Tang. 334/445 (ch. 99) |

| 101–110 | 11 | 𗦴 | L3333 | ²mi'₁ | coal | Tang. 334/486 (ch. 110) |

| 111–120 | 12 | 𗴵 | L0124 | ²luq₃ | peak | Tang. 334/241 (chs. 111–120) Tang. 334/483 (ch. 119) |

| 121–130 | 13 | 𗘞 | L0480 | ¹lha₄ | sage | Tang. 334/357 (chs. 121–130) Tang. 334/157 (ch. 121) Or. 12380/2130 (ch. 130) |

| 131–140 | 14 | 𗦖 | L3130 | ²mer₄ | palace | Tang. 334/527 (ch. 133) |

| 141–150 | 15 | 𗌽 | L0804 | ²dy₄ | (auxiliary particle) | Tang. 334/244 (chs. 141–150) Tang. 334/484 (ch. 148) |

| 151–160 | 16 | 𗰖 | L0478 | ¹sho'₃ | to gather | Tang. 334/250 (chs. 151–160) Tang. 334/211 (ch. 155) |

| 161–170 | 17 | 𗳄 | L0842 | ²kyr'₄ | sky | Tang. 334/251 (chs. 161–170) Tang. 334/529 (ch. 161) |

| 171–180 | 18 | 𗩆 | L2882 | ²gwi₄ | land | Tang. 334/252 (chs. 171–180) Tang. 334/554 (ch. 172) |

| 181–190 | 19 | 𗾚 | L3671 | ¹ne₄ | father | Tang. 334/253 (chs. 181–190) Tang. 334/546 (ch. 182) |

| 191–200 | 20 | 𗒷 | L4905 | ²rar₄ | parents | Tang. 334/255 (chs. 191–200) |

| 201–210 | 21 | 𗿼 | L2262 | ¹jwon₃ | bird | Tang. 334/258 (chs. 201–210) |

| 211–220 | 22 | 𗤈 | L2295 | ¹gi'₄ | to give birth to | Tang. 334/259 (chs. 211–220) Tang. 334/536 (ch. 220) |

| 221–230 | 23 | 𗈈 | L1210 | ²jan₂ | egg | Tang. 334/261 (chs. 221–230) |

| 231–240 | 24 | 𗇱 | L1188 | ²nga₁ | egg | Tang. 334/262 (chs. 231–240) |

| 241–250 | 25 | 𗿣 | L3111 | ²mer₄ | spirit | Tang. 334/260 (chs. 241–250) Tang. 334/629 (ch. 242) |

| 251–260 | 26 | 𗿷 | L3126 | ²je₃ | to have | Tang. 334/264 (chs. 251–260) Tang. 334/641 (ch. 256) |

| 261–270 | 27 | 𗋚 | L2590 | ²vy₃ | (prefix) | Tang. 334/263 (chs. 261–270) Tang. 334/643 (ch. 262) |

| 271–280 | 28 | 𗨄 | L2132 | ²ew₄ | achievement | Tang. 334/626 (ch. 272) |

| 281–290 | 29 | 𗉢 | L1751 | ¹shwa₃ | hand | Tang. 334/266 (chs. 281–290) |

| 291–300 | 30 | 𗰣 | L1012 | ¹zeq₄ | how many | Tang. 334/267 (chs. 291–300) |

| 301–310 | 31 | 𗸆 | L1467 | ¹khon₄ | strong | Kychanov 1999 p. 690 |

| 311–320 | 32 | 𘓳 | L1602 | ²ngorn₁ | whole, complete | Tang. 334/310 (chs. 311–320) |

| 321–330 | 33 | 𘛛 | L5319 | ¹ten₄ | sun | Tang. 334/311 (chs. 321–330) Tang. 334/199 (ch. 321) |

| 331–340 | 34 | 𘘞 | L1846 | ¹ka₁ | moon | Tang. 334/312 (chs. 331–340) Tang. 334/198 (ch. 331) |

| 341–350 | 35 | 𘛶 | L5223 | ²chyr'₃ | stars | Tang. 334/360 (chs. 341–350) |

| 351–360 | 36 | 𗅹 | L2375 | ¹a₄ | east | Tang. 334/231 (ch. 351) |

| 361–370 | 37 | 𘄉 | L0958 | ²ren₄ | dark | Tang. 334/358 (chs. 361–370) Tang. 334/234 (ch. 363) |

| 371–380 | 38 | 𗬕 | L3597 | ²mer₄ | dark | Kychanov 1999 p. 690 Or. 12380/536 |

| 381–390 | 39 | 𘀐 | L3849 | ¹zhiw₃ | six | Tang. 334/356 (chs. 381–390) Tang. 334/282 (ch. 387) |

| 𗰞 | L0176 | ¹na'₃ | black | Kychanov 1999 p. 690 | ||

| 391–400 | 40 | 𗆞 | L1945 | ²me₄ | to look into the distance | Tang. 334/270 (ch. 399) |

Table 3.2.1: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 310 (大寶積經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 73 | 𘒮 | L5869 | ²zew'₁ | to supervise | TT 8/1730 (ch. 1) |

| 11–20 | 74 | 𘞉 | L0262 | ¹le₁ | stone, pebble | TT 8/1801 (ch. 12) |

| 21–30 | 75 | 𗌜 | L3052 | ¹nor'₄ | water (坎) | TT 8/1856 (ch. 26) |

| 31–40 | 76 | 𗲟 | L1343 | ¹py₁ | ore | TT 8/1869 (ch. 31) Or. 12380/273 |

| 41–50 | 77 | 𗏂 | L1995 | ²mi₁ | wind (巽) | TT 8/1899 (ch. 50) |

| 51–60 | 78 | |||||

| 61–70 | 79 | |||||

| 71–80 | 80 | |||||

| 81–90 | 81 | |||||

| 91–100 | 82 | |||||

| 101–110 | 83 | |||||

| 111–120 | 84 |

Table 3.2.2: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 310 (大寶積經)

This table lists the index characters as given in Kychanov 1999 p. 690, which are somewhat different from the index characters that I have seen in the texts reproduced in Grinstead 1971.

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 73 | 𘞉 | L0262 | ¹le₁ | ore, stone | Kychanov 1999 p. 690 |

| 11–20 | 74 | 𗌜 | L3052 | ¹nor'₄ | water | |

| 21–30 | 75 | 𗲟 | L1343 | ¹py₁ | ore | |

| 31–40 | 76 | 𗦴 | L3333 | ²mi'₁ | coal | |

| 41–50 | 77 | 𗾈 | L3294 | ²mi'₁ | virtuous person | |

| 51–60 | 78 | 𗰜 | L0856 | ²myr₁ | origin | |

| 61–70 | 79 | 𘝨 | L4861 | ²zoq₄ | time | |

| 71–80 | 80 | 𗰱 | L0678 | ¹gu₁ | to happen | |

| 81–90 | 81 | 𘘮 | L0261 | ²mo₄ | I | |

| 91–100 | 82 | 𗸦 | L0545 | ¹jwu₃ | human being | |

| 101–110 | 83 | 𗨛 | L2511 | ²ryr₄ | to arise | |

| 111–120 | 84 | 𗟲 | L1014 | ¹ngwu'₁ | speech |

Table 3.3: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 293 (大方廣佛華嚴經)

Kychanov 1999 p. 690 gives two sets of index characters for 大方廣佛華嚴經. One set comprises the eight characters of the Tangut title for Taishō No. 279 (see Table 1 above), and are not listed here. The other set mixes up the index characters for Taishō No. 279 [80 chs.] and Taishō No. 293 [40 chs.] : index characters 3 and 5–8 belong to Taishō No. 279; index character 2 and 4 belong to Taishō No. 293; and index character 1 is assumed to belong to Taishō No. 293.

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 105 | 𗤻 | L2467 | ¹vaq₃ | flower | Kychanov 1999 p. 690 |

| 11–20 | 106 | 𗅛 | L2826 | ²len₃ | sun | TT 7/1648 (ch. 17) |

| 𗆋 | L2902 | ¹shwy₃ | to cry | Kychanov 1999 p. 690 | ||

| 21–30 | 107 | |||||

| 31–40 | 108 | 𗏴 | L2149 | ¹ju₃ | to show | TT 8/1704 (ch. 32) |

| 41–50 | 109 |

Table 3.4: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 279 (大方廣佛華嚴經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 110 | 𗥤 | L3574 | ²tse₄ | to know | TT 7/1529 (ch. 4) |

| 11–20 | 111 | 𗵜 | L0133 | ²lwyr₁ | resource | TT 2/258 (ch. 11) TT 7/1553 (ch. 19) |

| 21–30 | 112 | 𗄷 | L2823 | ²my₁ | to produce | TT 2/309 (ch. 22) TT 7/1565 (ch. 24) |

| 31–40 | 113 | 𘟪 | L4995 | ¹shon₃ | iron | TT 2/381 (ch. 31) |

| 41–50 | 114 | 𘙎 | L0354 | ²lhi₄ | to give birth to | TT 3/514 (ch. 44) Pelliot Chinois 10065 (ch. 41) |

| 51–60 | 115 | 𗿾 | L2268 | ¹viq₃ | east | TT 3/568 (ch. 51) TT 7/1590 (ch. 55) |

| 61–70 | 116 | 𗡴 | L0807 | ¹shwa₃ | river | TT 3/676 (ch. 62) |

| 71–80 | 117 | 𗅓 | L2917 | ²ne₄ | mountain | TT 4/793 (ch. 71) TT 7/1612 (ch. 77) PUDL BQ1623.T3 T35 (ch. 77) |

Table 3.5.1: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 374 (大般涅槃經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 122 | 𗩯 | L3576 | ¹swe₄ | clear | TT 8/1914 (ch. 2) |

| 11–20 | 123 | 𘜍 | L0811 | ²ar'₄ | date | TT 9/1973 (ch. 13) |

| 𘘙 | L0742 | ¹jeq₂ | to surround | Kychanov 1999 p. 691 | ||

| 21–30 | 124 | 𗱨 | L0931 | ²lu'₃ | bedding; to sleep | Tang. 335/10 (ch. 22) [end title] |

| 𘟢 | L0373 | ²vi₁ | to mate | Kychanov 1999 p. 691 | ||

| 31–40 | 125 | 𗡮 | L0541 | ²lu'₃ | beautiful | Kychanov 1999 p. 691 |

Table 3.5.2: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 374 (大般涅槃經)

Kychanov 1999 p. 691 gives two sets of index characters for 大般涅槃經. The second set is listed in this table for reference. The index characters for chs. 1–10 and 11–20 may represent the word nirvāṇa, which is part of the title of this text, and an indication that these index characters may belong to a different system than the index characters used elsewhere.

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 122 | 𘈬 | L1722 | ²de'₄ | (transcription of the first syllable of nirvāṇa) | Kychanov 1999 p. 691 |

| 11–20 | 123 | |||||

| 21–30 | 124 | 𘍺 | L5499 | ¹vi₁ | dawn | |

| 31–40 | 125 | 𗶏 | L1401 | ²lu'₃ | imperial concubine |

Table 3.6: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 262 (妙法蓮華經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–8 | 130 or 132 | 𗿸 | L3703 | ²vi₁ | title | PUDL BQ2053.T3 T38 (ch. 4) |

Table 3.7: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 157 (悲華經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 135 | 𗩟 | L3318 | ¹cheq₃ | year | TT 1/2 (ch. 9) |

Table 3.8: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 660 (佛説寶雨經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 139 | 𗦥 | L2117 | ¹dzen₄ | divination | TT 9/2053 (ch. 10) |

Table 3.9: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 446 (過去莊嚴劫千佛名經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 184 | 𗹚 | L0631 | ¹ner₄ | soil, land | TT 4/906 |

Table 3.10: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 1509 (大智度論)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81–90 | 216 | 𘃦 | L5694 | ¹ly'₃ | to do | Pelliot Xixia 924/110 (ch. 87) |

Table 3.11: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 1605 (大乘阿毘達磨集論)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–7 | 235 | 𗭧 | L4009 | ¹dyq₄ | to smash; grain | TT 9/2219 (ch. 3) |

Table 3.12: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 201 (大莊嚴論經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 244/245 | 𗈿 | L1829 | ¹tsha₄ | to heat up | TT 6/1231 (ch. 1) |

Table 3.13: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 64 (瞻婆比丘經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 282 | 𗂰 | L2945 | ²li₃ | west | TT 6/1229 |

Table 3.14: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 721 (正法念處經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61–70 | 295 | 𘄎 | L1638 | ¹gi₄ | clear | Pelliot Xixia 924/117 (ch. 67) |

Table 3.15: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 1453 (根本説一切有部百一羯磨)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 339 | 𗞝 | L4115 | ²ge₄ | wilderness | TT 9/2218 (ch. 4) |

Table 3.16: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 1562 (阿毘達磨順正理論)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 397 | 𗲈 | L0933 | ²ghew₄ | jade bi (璧) | TT 5/1053 (ch. 5) |

Table 3.17: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 2121 (經律異相)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 440 | 𗤳 | L2888 | ²my₁ | surname | See Fig. 7 (ch. 1) |

Table 3.18: List of index characters in the Tangut translation of Taishō No. 439 (佛説諸佛經)

| Chaps. | KSL No. | Glyph | Ref. | Reading | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A | 𗗙 | L1139 | ¹e₄ | (possessive particle) | TT 9/1996 |

Looking at the list of Tangut index characters, it is clear that they are not just random characters, as many sequences of two characters form well-attested collocations (e.g. "heaven and earth", "sun and moon", and the two-character words for "dark" and "egg"). Moreover, there is a definite structure to the sequence of characters, with a basic semantic unit of four characters (e.g. characters 21–24, "birds lay eggs"). In short, the list of index characters forms a literary text divided into lines of four characters. This text does not show any indication of rhyme or tonal structure, such as one might find in Chinese poetry, but this four-character line structure does mirror the structure of the Chinese QZW. The first two characters in QZW, "heaven and earth" (tiān dì 天地), are the same as the first two characters of the Tangut text, which confirms that it is correct to order the Tangut texts according to their order in KSL (or, at the very least, it is correct to put GPWS first). However, only the first two characters correspond, and thereafter the Tangut text does not reflect the sense of QZW. Although the Tangut text is not a translation of QZW, it does consist of four-character lines with no repeating characters, just like QZW, and so it can be considered to be an otherwise unattested Tangut version of a thousand-character text. Hereafter, I shall refer to this text as the Tangut Thousand Character Text [TTCT]. It has to be admitted that at this stage we cannot be certain that all the index characters in texts other than GPWS belong to this thousand-character text, and in some cases Kychanov 1999 notes different index characters for the same chapters of the same text. Nevertheless, my working hypothesis is that most of the index characters listed in the tables above (excluding Table 3.5.2) do belong to the same thousand character text (this thesis will be developed in Part 2 of this post).

Common Tangut and Odic Tangut

There is another Tangut text that also comprises a thousand unique characters, Newly Collected Grains of Gold Placed in the Palm 𗆧𗰖𗵒𗭭𘃎𘐏𘝞 siw sho ki dy pa ti wyr (Chinese Xīnjí Suìjīn Zhìzhǎngwén 新集碎金置掌文). This was a popular pedagogical text, and is known from a number of manuscripts and fragments. Although Grains of Gold and TTCT are both composed from a thousand unique characters, they are completely different texts, and in contrast to the four-character structure of QZW and TTCT, Grains of Gold is divided into 200 five-character lines.

Fig. 9: Grains of Gold [IOM Tang. 30 Inv. No. 741] folio 2a

The opening line, "Heaven and earth, the world long ago; The sun and the moon appear at that time", are at the top of the 4th column of text from the right.

The difference in line structure is not the only difference between Grains of Gold and TTCT. The most significant difference between the two texts is their use of language. This can be seen from the first two characters of each text. In both cases, the first two characters mean "heaven and earth", mirroring the opening words of the Chinese QZW, but they each use different characters to represent this meaning.

The characters used in Grains of Gold are those normally used in Tangut texts to designate "heaven" and "earth", i.e. ¹my₁ 𗹦 and ²lyq₃ 𗼻 respectively. They are, for example, used as two of the three primary lexicographic divisions ("Heaven", "Earth" and "Man") in the Tangut glossaries Pearl in the Palm of the Hand (Tangut mi zar dzen bu pa gu ni 𗼇𘂜𗿳𗖵𘃎𘇂𗊏; Chinese Fān-Hàn Héshí Zhǎngzhōngzhū 番漢合時掌中珠) and Miscellaneous Characters (Tangut di dza 𗏇𘉅; Chinese Zázì 雜字).

On the other hand, the two characters used in TTCT to mean "heaven" and "earth", ¹tshwu₄ 𘀗 and ¹tsir₁ 𗿀 respectively, are rarely found in other Tangut texts, and are only used in special contexts, such as in the era name Qianyou 乾祐 "Heaven Aids" (tshwu wu 𘀗𘑨), and in the name of the planet Saturn (tsir ge 𗿀𗵫 = Chinese tǔ xīng 土星 "earth star"). However, there is one text where these two characters are frequently used, that is a collection of five odic poems (dzo 𗊱), which are written in two parallel versions, one version using ordinary Tangut vocabulary, and one version using predominantly unusual Tangut vocabulary which Ksenia Kepping has designated "ritual language" (see my The Myth of the Tangut Ritual Language and A new interpretation of the Ode on Monthly Pleasure for preliminary discussions of the language of the Tangut odes). Hereafter I shall refer to these two different styles of Tangut language as Common Tangut and Odic Tangut respectively (see Marc Miyake's O Moon, O Sun! for various suggestions for alternative designations).

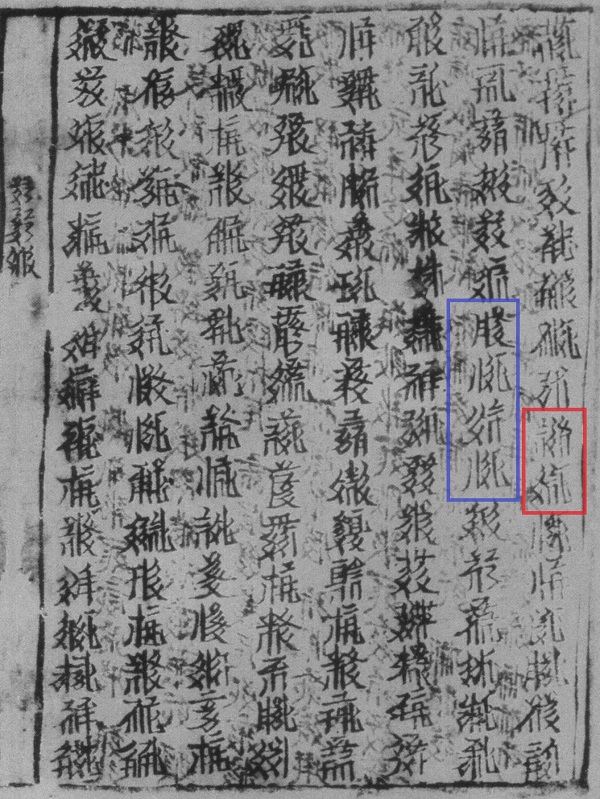

Fig. 10: Odes [IOM Tang. 25 Inv. No. 121] No. 4 folio 3a

The characters for "heaven" and "earth" marked in blue (my non ly non 𗹦𗅉𗼻𗅉) are part of the Common Tangut version of the ode; whereas the characters for "heaven" and "earth" marked in red (tshwu tsir 𘀗𗿀) are part of the Odic Tangut version of the ode.

Hiatus

At this point I am going to take a break from this post, and plan to continue with Part 2 in the autumn of 2015. In Part 2 I will examine the thousand character text that the index characters form when read sequentially in some more detail, and analyse the lexical usage of the reconstructed text with reference to the five poetic odes and other Tangut texts. I will also provide an annotated translation into English of at least the portion of the text covered by GPWS.

Bibliography

Grinstead, Eric (ed.). 1971. The Tangut Tripiṭaka parts 1–9 (Śata-piṭaka series 83–91). New Delhi: Sharada Rani.

Kychanov, E. I. 1999. Каталог тангутских буддийских памятников Института востоковедения Российской Академии Наук [Catalogue of Tangut Buddhist Texts Kept at the Institute of Oriental Studies, RAS]. Kyoto: University of Kyoto, 1999.

Li Fanwen 李範文. 2008. Xià-Hàn Zìdiàn 夏漢字典 [Tangut-Chinese Dictionary]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe.

Miyake, Marc. 2015. "Tangut Phonetic Database Version 1.0". 1 February 2015.

Nie Hongyin 聶鴻音 and Shi Jinbo史金波. 1995. "Xīxiàwénběn Suìjīn Yánjiū" 西夏文本《碎金》研究 [Study of the Tangut version of the 'Sui Jin']. Journal of Ningxia University 1995 no. 2.

Nishida Tatsuo 西田龍雄. 1977. "西夏譯佛典目錄" [Catalogue of Tangut translations of Buddhist texts], in Seikabun Kegonkyō 西夏文華嚴經 [The Hsi-Hsia Avataṁsaka sūtra] (Kyoto, 1975–1977) vol. 3 pp. 13–59.

Rong, Xinjiang (Valerie Hansen trans.). 1999. "The Nature of the Dunhuang Library Cave and the Reasons for its Sealing". In Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie 11, 247–275.

Stein, M. Aurel. 1912. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal Narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China. London: Macmillan and Co.

Stein, Aurel. 1921. Serindia: Detailed Report of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Whitfield, Roderick and Anne Farrer. 1990. Caves of the Thousand Buddhas: Chinese Art from the Silk Route. London: British Museum Publications.

Whitfield , Susan. 2002. Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries. London: British Library.

Wilkinson, Endymion. 2013. Chinese History: A New Manual. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

Last modified: 2022-05-24

If Tangut characters do not display correctly, please download and install the Tangut Yinchuan font.

Index of BabelStone Blog Posts