BabelStone Blog

Monday, 12 June 2006

The Rules for Long S

In my previous post about the grand old trade of basket-making I included several extracts from some 18th century books, in which I preserved the long s (ſ) as used in the original printed texts. This got me thinking about when to use long s and when not. Like most readers of this blog I realised that long s was used initially and medially, whereas short s was used finally (mirroring Greek practice with regards to final lowercase sigma ς and non-final lowercase sigma σ), although there were, I thought, some exceptions. But what exactly were the rules ?

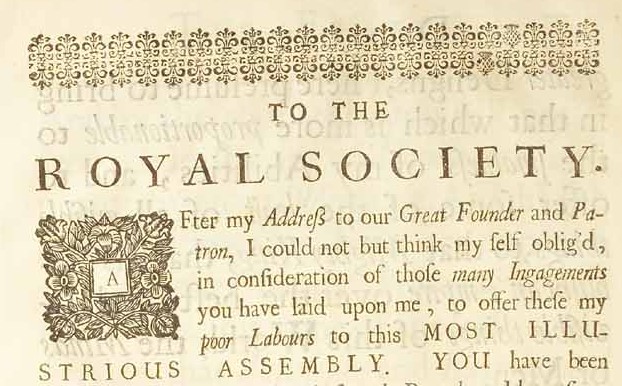

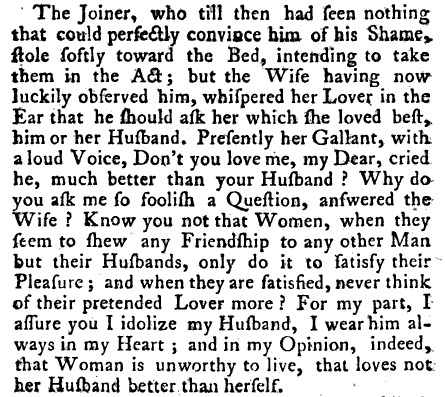

"The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green" in Robert Dodsley's Triffles (London, 1745)

(In roman typeface f and ſ are very similar but are easily distinguished by the horizontal bar, which goes all the way through the vertical stem of the letter 'f' but only extends to the left of the vertical stem of the long s; and in italic typeface long s is even more clearly distinguished from the letter 'f' as it has no horizontal bar at all)

Turning first to my 1785 copy of Thomas Dyche's bestselling A Guide to the English Tongue (first published in 1709, or 1707 according to some, and reprinted innumerable times over the century) for some help from a contemporary grammarian, I was confounded by his advise that :

The long ſ muſt never be uſed at the End of a Word, nor immediately after the short s.

Well, I already knew that long s was never used at the end of a word, but why warn against using long s after short s when short s should only occur at the end of a word ?

The 1756 edition of Nathan Bailey's An Universal Etymological English Dictionary also gives some advise on the use of long s (although this advise does not seem to occur in the 1737 or 1753 editions) :

A long ſ muſt never be placed at the end of a word, as maintainſ, nor a ſhort s in the middle of a word, as conspires.

Similarly vague advise is given in James Barclay's A Complete and Universal English Dictionary (London, 1792) :

All the ſmall Conſonants retain their form, the long ſ and the ſhort s only excepted. The former is for the moſt part made uſe of at the beginning, and in the middle of words ; and the laſt only at their terminations.

I felt sure that John Smith's compendious Printer's Grammar (London, 1787) would enumerate the rules for the letter 's', but I was disappointed to find that although it gives the rules for R Rotunda, the rules for long s are not given, save for one obscure rule (see Short ST Ligature after G below) which does not seem to be much used in practice.

So, all in all, none of these contemporary sources are much help in the finer details of how to use long s. The internet turns up a couple of useful documents : Instructions for the proper setting of Blackletter Typefaces discusses the rules for German Fraktur typesetting ; whilst 18th Century Ligatures and Fonts by David Manthey specifically discusses 18th century English typographic practice. According to Manthey long s is not used at the end of the word or before an apostrophe, before or after the letter 'f', or before the letters 'b' and 'k' , although he notes that some books do use a long s before the ketter 'k'. This is clearly not the entire story, because long s does commonly occur before both 'b' and 'k' in 18th century books on my bookshelves, including, for example, Thomas Dyche's Guide to the English Tongue.

To get the bottom of this I have enlisted the help of Google Book Search (see note at bottom of the post) to empirically check what the usage rules for long s and short s were in printed books from the 16th through 18th centuries. It transpires that the rules are quite complicated, with various exceptions, and vary subtly from country to country as well as over time. I have summarised below my current understanding of the rules as used in roman and italic typography in various different countries, and as I do more research I will expand the rules to cover other countries. At present I do not cover the rules for the use of long s in blackletter or fraktur typography, but may do so in the future. It should also be noted that the rules for the use of long s in typography do not necessarily correspond to the usage of long s in handwriting, and in 18th century handwritten letters and documents long s is generally much more restricted in usage than in printed books from the same place and time. I am planning to write a separate post on long s in handwritten English in February 2013.

Rules for Long S in English

The following rules for the use of long s and short s are applicable to books in English, Welsh and other languages published in England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and other English-speaking countries during the 17th and 18th centuries.

- short s is used at the end of a word (e.g. his, complains, ſucceſs)

- short s is used before an apostrophe (e.g. clos'd, us'd)

- short s is used before the letter 'f' (e.g. ſatisfaction, misfortune, transfuſe, transfix, transfer, ſucceſsful)

- short s is used after the letter 'f' (e.g. offset), although not if the word is hyphenated (e.g. off-ſet) [see Short S before and after F for details]

- short s is used before the letter 'b' in books published during the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century (e.g. husband, Shaftsbury), but long s is used in books published during the second half of the 18th century (e.g. huſband, Shaftſbury) [see Short S before B and K for details]

- short s is used before the letter 'k' in books published during the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century (e.g. skin, ask, risk, masked), but long s is used in books published during the second half of the 18th century (e.g. ſkin, aſk, riſk, maſked) [see Short S before B and K for details]

- Compound words with the first element ending in double s and the second element beginning with s are normally and correctly written with a dividing hyphen (e.g. Croſs-ſtitch, Croſs-ſtaff), but very occasionally may be written as a single word, in which case the middle letter 's' is written short (e.g. Croſsſtitch, croſsſtaff).

- long s is used initially and medially except for the exceptions noted above (e.g. ſong, uſe, preſs, ſubſtitute)

- long s is used before a hyphen at a line break (e.g. neceſ-ſary, pleaſ-ed), even when it would normally be a short s (e.g. Shaftſ-bury and huſ-band in a book where Shaftsbury and husband are normal), although exceptions do occur (e.g. Mans-field)

- double s is normally written as double long s medially and as long s followed by short s finally (e.g. poſſeſs, poſſeſſion), although in some late 18th and early 19th century books a different rule is applied, reflecting contemporary usage in handwriting, in which long s is used exclusively before short s medially and finally [see Rules for Long S in some late 18th and early 19th century books for details]

- short s is used before a hyphen in compound words with the first element ending in the letter 's' (e.g. croſs-piece, croſs-examination, Preſs-work, bird's-neſt)

- long s is maintained in abbreviations such as ſ. for ſubſtantive, and Geneſ. for Geneſis (this rule means that it is practically impossible to implement fully correct automatic contextual substitution of long s at the font level)

Usage in 16th and early 17th century books may be somewhat different (see Rules for Long S in Early Printed Books for details), and books in English published in continental Europe may not apply the same rules [for example, Henry St. John Bolingbroke's Letters on the Study and Use of History (Basil: J. J. Tourneisen, 1788) and Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Basil: J. J. Tourneisen, 1789) apply French typographic rules, with short s before the letters 'h', 'b' and 'k']. Most importantly, the above rules do not necessarily apply to handwriting, as long s was generally restricted to being used before short s medially and finally (e.g. poſseſs) in most 18th century English handwritten letters and documents.

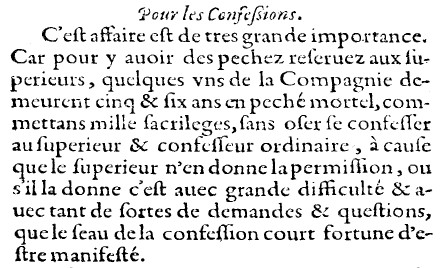

Rules for Long S in French

The rules for the use of long s in books published in France and other French-speaking countries during the 17th and 18th centuries are much the same as those used in English typography, but with some significant differences, notably that short s was used before the letter 'h'.

- short s is used at the end of a word (e.g. ils, hommes)

- short s is used before an apostrophe (e.g. s'il and s'eſt)

- short s is used before the letter 'f' (e.g. ſatisfaction, toutesfois)

- short s is used before the letter 'b' (e.g. presbyter)

- short s is used before the letter 'h' (e.g. déshabiller, déshonnête)

- long s is used initially and medially except for the exceptions noted above (e.g. ſans, eſt, ſubſtituer)

- long s is normally used before a hyphen at a line break (e.g. leſ-quels, paſ-ſer, déſ-honneur), although I have seen some books where short s is used (e.g. les-quels, pas-ſer, dés-honneur)

- short s is normally used before a hyphen in compound words (e.g. tres-bien), although I have seen long s used in 16th century French books (e.g. treſ-bien)

- long s is maintained in abbreviations such as Geneſ. for Geneſis

Rules for Long S in Italian

The rules for the use of long s in books published in Italy seem to be basically the same as those used in French typography :

- short s is used at the end of a word

- short s is used before an apostrophe (e.g. s'informaſſero, fuſs'egli)

- short s is used before an accented vowel (e.g. paſsò, ricusò, sù, sì, così), but not an unaccented letter (e.g. paſſo, ſi)

- short s is used before the letter 'f' (e.g. ſoddisfare, ſoddisfazione, trasfigurazione, sfogo, sfarzo)

- short s is used before the letter 'b' (e.g. sbaglio, sbagliato)

- long s is used initially and medially except for the exceptions noted above

- long s is used before a hyphen in both hyphenated words and at a line break (e.g. reſtaſ-ſero)

The most interesting peculiarity of Italian practice is the use of short s before an accented vowel, which is a typographic feature that I have not noticed in French books.

In some Italian books I have occaionally seen double s before the letter 'i' writen as long s followed by short s (e.g. utiliſsima, but on the same page as compreſſioni, proſſima, etc.). And in some 16th century Italian books double s before the letter 'i' may be written as a short s followed by a long s. See Rules for Long S in Early Printed Books below for details.

Rules for Long S in Spanish

It has been a little more difficult to ascertain the rules for long s in books published in Spain as Google Book Search does not return many 18th century Spanish books (and even fewer Portuguese books), but I have tried to determine the basic rules from the following three books :

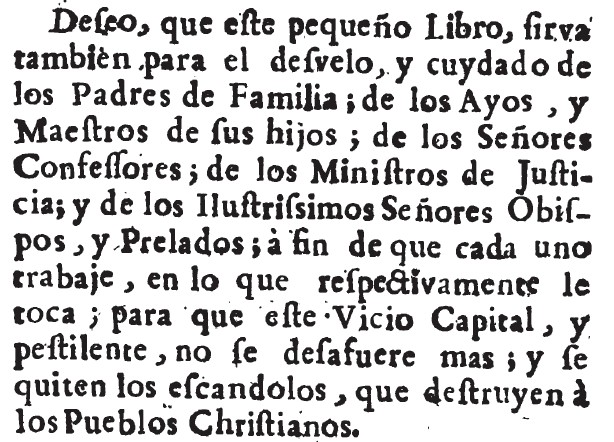

- Estragos de la Luxuria (Barcelona, 1736)

- Autos sacramentales alegoricos, y historiales del Phenix de los Poetas el Espanol (Madrid, 1760)

- Memorias de las reynas catholicas (Madrid, 1770)

From these three books it appears that the rules for Spanish books are similar to those for French books, but with the important difference that (in both roman and italic type) the sequence ſs (not a ligature) is used before the letter 'i', whereas the sequence ſſ is used before all other letters (e.g. illuſtriſsimos but confeſſores) :

Estragos de la Luxuria (Barcelona, 1736)

In summary, the rules for Spanish books are :

- short s is used at the end of a word

- short s may be used before an accented vowel (e.g. sí, sì, sé, sè, Apoſtasìa, Apoſtasía, abrasò, paſsò), but not an unaccented letter (e.g. ſi, ſe, paſſo)

- short s is used before the letter 'f' (e.g.transformandoſe, transfigura, ſatisfaccion)

- short s is used before the letter 'b' (e.g. presbytero)

- short s is used before the letter 'h' (e.g. deshoneſtos, deshoneſtidad)

- short s is used after a long s and before the letter 'i' (e.g. illuſtriſsimo, paſsion, confeſsion, poſsible), but double long s is used before any letter other than the letter 'i' (e.g. exceſſo, comiſſario, neceſſaria, paſſa)

- long s is used initially and medially except for the exceptions noted above

- long s is used before a hyphen in both hyphenated words and at a line break, even when it would normally be a short s (e.g. tranſ-formados, copioſiſ-ſimo)

As with Italian books, Spanish books usually use a short s before an accented vowel, although from the three books that I have examined closely it is not quite clear what the exact rule is. For example, Memorias de las reynas catholicas (Madrid, 1770) consistantly uses short s before an accented letter 'i' (e.g. sí), but consistantly uses a long s before an accented letter 'o' (e.g. paſſó, caſó, preciſó, Caſóle); whereas Estragos de la Luxuria (Barcelona, 1736) uses short s both before an accented letter 'i' (e.g. sì) and an accented letter 'o' (e.g. abrasò, paſsò).

Rules for Long S in Other Languages

Other languages may use different rules to those used in English and French typography. For example, my only early Dutch book, Simon Stevin's Het Burgerlyk Leven [Vita Politica] (Amsterdam, 1684) follows the German practice of using short s medially at the end of the elements of a compound word (e.g. misverſtants, Rechtsgeleerden, wisconſtige, Straatsburg, Godsdienſten, misgaan, boosheyt, dusdonig and misbruyk).

Rules for Long S in Early Printed Books

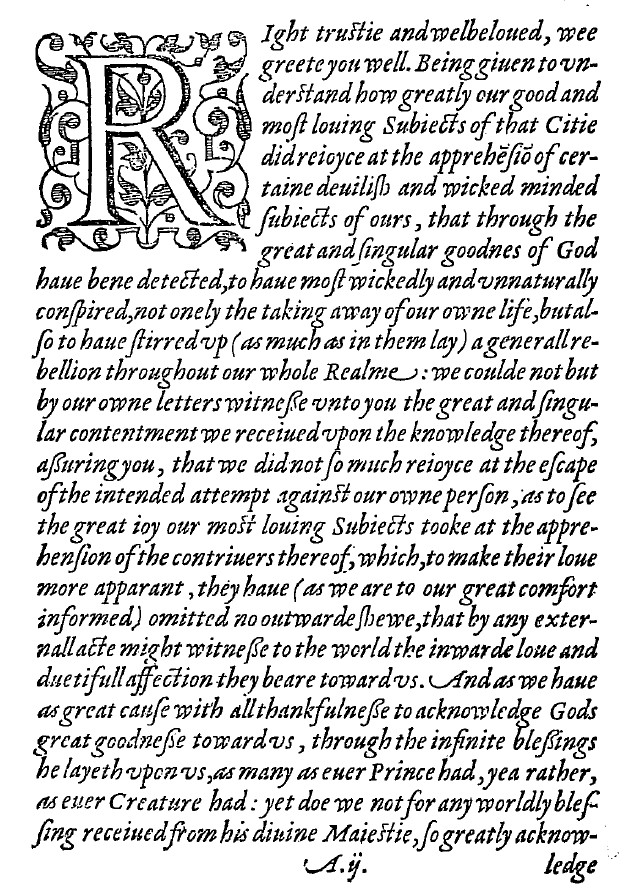

In 16th century and early 17th century books printed in roman or italic typefaces (as opposed to blackletter) the rules for the use of long s may be slightly different to those enumerated above. For example, in italic text it was common to use a ligature of long s and short s (ß) for double-s, whereas a double long s ligature was normally used in roman text. This can be seen in the following extract from an English pamphlet published in 1586, which has the words witneße, aßuring, thankfulneße, goodneße and bleßings :

The True Copie of a Letter from the Qveenes Maiestie (London, 1586)

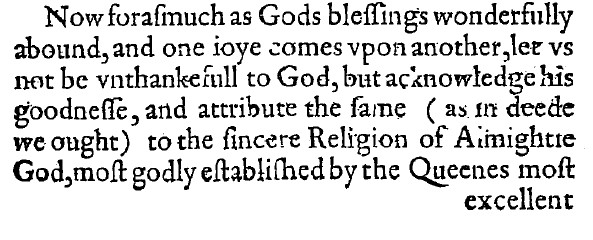

But in that part of the same pamphlet that is set in roman typeface the words bleſſings and goodneſſe are written with a double long s ligature :

And this French book published in 1615 has Confeßions in italic type, but confeſſion in roman type :

Advis de ce qu'il y a à reformer en la Compagnie des Jesuites (1615) page 13

This ligature is still occasionally met with in a word-final position in italic text late into the 17th century, for example in this page from Hooke's Micrographia, which has this example of the word Addreß, although unligatured long s and short s are used elsewhere at the end of a word (e.g. ſmalneſs) as well as occasionally in the middle of a word (e.g. aſsiſted, alongside aſſiſtances) in italic text.

Micrographia (London, 1665) page 13

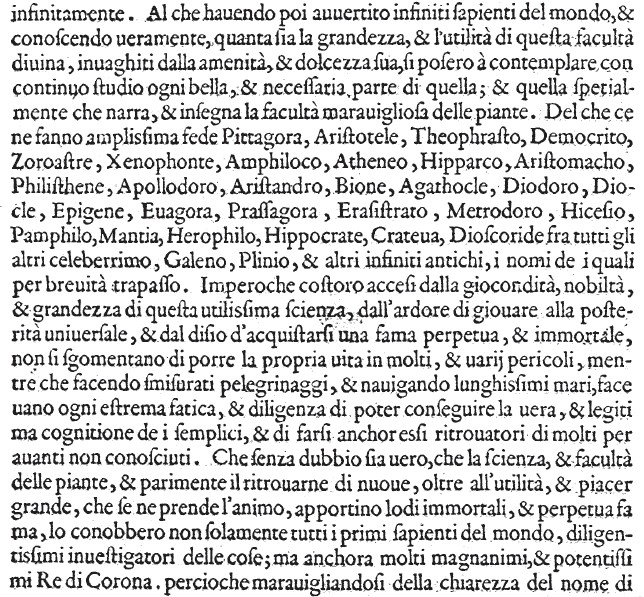

Another peculiarity that is seen in some 16th century Italian books is the use of short s before long s medially before the letter 'i', but double long s before any other letter :

I Discorsi di M. Pietro And. Matthioli (Venice, 1563)

amplisſima, utilisſima, longhisſimi, diligentisſimi, etc., but note potentiſſi-mi at the end of the second to last line; cf. neceſſaria, Praſſagora, trapaſſo

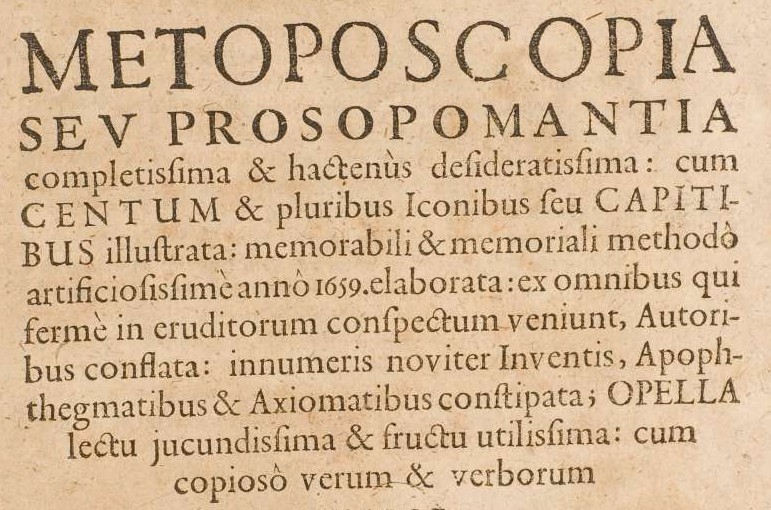

This typographic feature can also be seen in some later books, though I am not yet sure how widespread it was :

Title Page to Metoposcopia (Leipzig, 1661)

completisſima, deſideratisſima, artificioſisſmè, jucundisſima, utilisſima

Short S before and after F

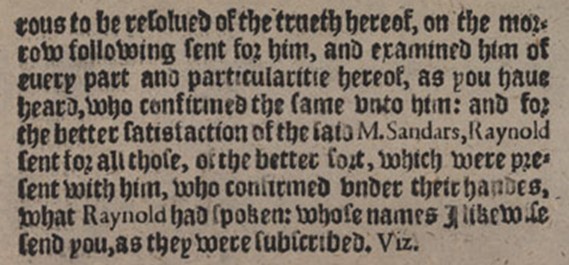

In 17th and 18th century English and French typography the main exceptions to the rule that short s is not used at the start of a word or in the middle of a word is that short s is used next to a letter f instead of the expected long s (so misfortune and offset, but never miſfortune or offſet). The reason for this must be related to the fact that the two letters ſ and f are extremely similar, although as the combination of the two letters does not cause any more confusion to the reader than any other combination of long s and another letter (the combinations fl and ſl are far more confusable) it does not really explain why long s should be avoided before or after a letter 'f', other than perhaps for aesthetic reasons. In all probability the rule is inherited from blackletter usage, as is evidenced by this 1604 pamphlet about a mermaid that was sighted in Wales, which has ſatisfaction :

Whatever the reasons, this is an absolute rule, and Google Book Search only finds a handful of exceptions from the 17th and 18th century, which are most probably typographical errors (or in the case of the Swedish-English dictionary due to unfamiliarity with English typographical rules) :

- miſfortune in Anglorum Speculum (London, 1684) [but misfortune elsewhere]

- ſatiſfie and ſatiſfied in The Decisions of the Lords of Council and Session (Edinburgh, 1698)

- miſfortune in The annals of the Church (London, 1712) [but misfortune elsewhere]

- miſfortune in An Historical Essay Upon the Loyalty of Presbyterians (1713) [but misfortune elsewhere]

- ſatiſfaction in An Enquiry Into the Time of the Coming of the Messiah (London, 1751) [but on the same page as ſatisfied]

- miſfortune in Svenskt och engelskt lexicon (1788)

Similarly, Google Book Search finds 628 French books published between 1700 and 1799 with ſatisfaction but only two books with ſatiſfaction.

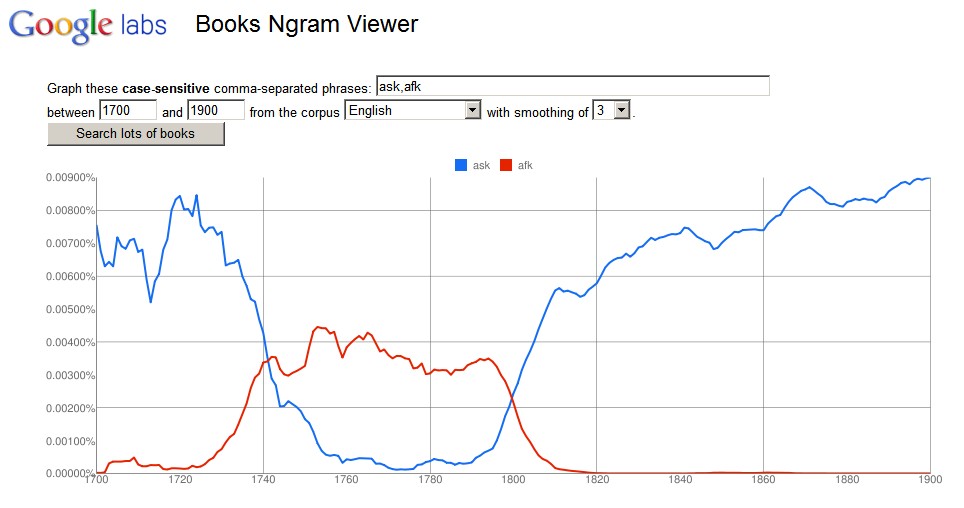

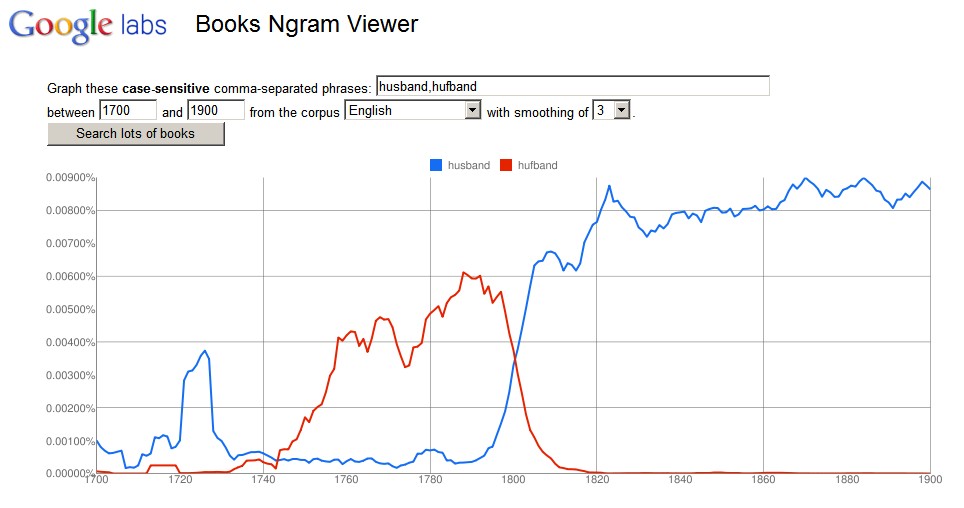

Short S before B and K

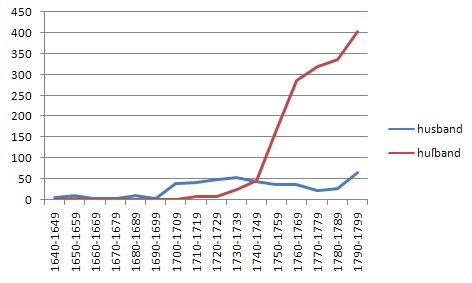

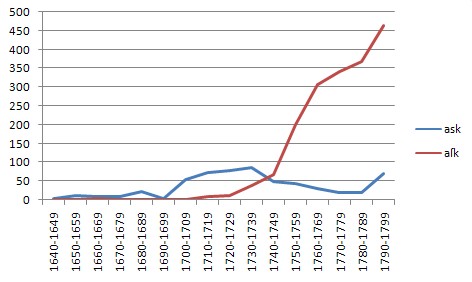

As a general rule English books published in the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century have a short s before the letters 'b' and 'k' (so husband and ask), whereas books published during the second half of the 18th century have a long s (so huſband and aſk).

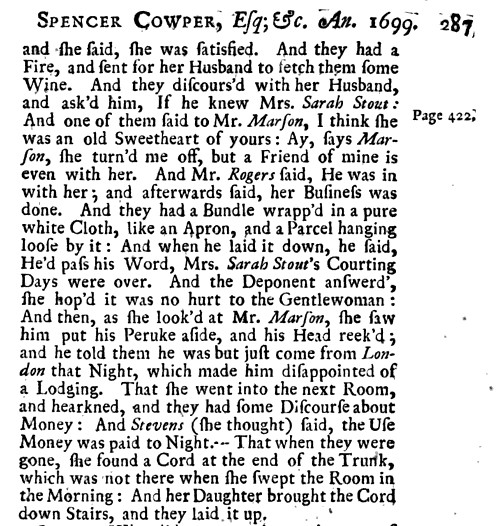

Tryals for High-Treason Part V (London, 1720) p.287

Short s before b and k: Husband, ask'd

The Instructive and Entertaining Fables of Pilpay (London, 1775) p.215

Long s before b and k: Huſband, aſk

This is not a hard and fast rule, as it is possible to find examples of books from the 17th and early 18th century that show huſband and aſk, but they are few and far between. For example, whereas Google Book Search finds 138 books published between 1600 and 1720 with husband, Google Book Search only finds nine genuine books from this period that have huſband (excluding false positives and hyphenated huſ-band), and in almost all cases huſband is not used exclusively :

- The Dutch Courtezan (London, 1605) [mostly husband but a couple of instances of huſband]

- The breast-plate of faith and love (London, 1651) [mostly husband but one instance of huſband]

- Tryon's Letters, Domestick and Foreign, to Several Persons of Quality (London, 1700)

- The Present State of Trinity College in Cambridge (London, 1710) [mostly husband but one instance of huſband]

- Dialogue between Timothy and Philatheus (London, 1711) [one instance each of husband and huſband]

- The Universal Library; Or, Compleat Summary of Science (1712) [two instances of huſband]

- The Works of Petronius Arbiter (London, 1714) [mixture of both husband and huſband]

- Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy (London, 1718) [mostly husband but a couple of instances of huſband]

- An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft (London, 1718) [mostly husband but one instance of huſband]

Likewise, it is possible to find books from the late 18th century that use long s but show husband and ask, but these are relatively few in number. For example, whereas Google Book Search finds 444 books published between 1760 and 1780 that have huſband, it only finds 60 that have husband (excluding false positives on HUSBAND).

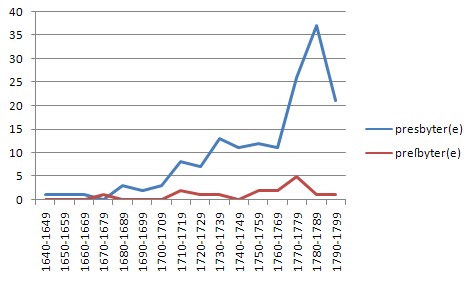

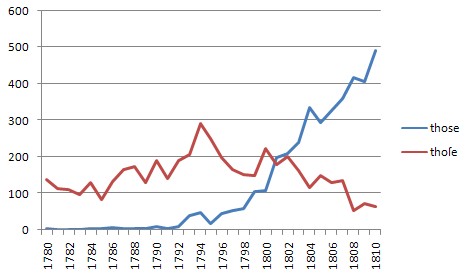

The results of Google Book Search searches on the two spellings of husband and ask (as well as presbyter(e) in French books) from 1640 to 1799 are tabulated below in ten-year segments (matches for HUSBAND and ASK have been discounted, but otherwise figures have not been adjusted for false positives such as huſ-band).

| Date | husband | huſband | ask | aſk | presbyter(e) | preſbyter(e) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1640–1649 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1650–1659 | 12 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1660–1669 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 1670–1679 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1680–1689 | 12 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 1690–1699 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 1700–1709 | 39 | 1 | 54 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 1710–1719 | 42 | 8 | 74 | 7 | 8 | 2 |

| 1720–1729 | 49 | 8 | 78 | 11 | 7 | 1 |

| 1730–1739 | 53 | 25 | 87 | 36 | 13 | 1 |

| 1740–1749 | 44 | 46 | 50 | 66 | 11 | 0 |

| 1750–1759 | 37 | 168 | 43 | 201 | 12 | 2 |

| 1760–1769 | 36 | 286 | 30 | 307 | 11 | 2 |

| 1770–1779 | 22 | 320 | 21 | 342 | 26 | 5 |

| 1780–1789 | 27 | 337 | 21 | 368 | 37 | 1 |

| 1790–1799 | 65 | 404 | 71 | 464 | 21 | 1 |

The change in the usage of short s to long s before 'b' and 'k' appears even more dramatic if these figures are plotted on a graph :

But for French books, no change in rule occured in the middle of the century, and short s continued to be used in front of the letter 'b' throughout the 18th century, as can be seen from the distribution of the words presbyter(e) and preſbyter(e) :

So why then did the change in rule for 's' before 'b'and 'k' happen in England during the 1740s and 1750s ? According to John Smith's Printer's Grammar (London, 1787) page 45 the Dutch type that was most comonly used in England before the advent of the home-grown typefaces of William Calson did not have "ſb" or "ſk" ligatures, and that it was Caslon who first cast "ſb" and "ſk" ligatures. So with the growth in popularity of Caslon's typefaces ligatured "ſb" and "ſk" took the place of "sb" and "sk"—but further research is required to confirm to this hypothesis.

As to why this rule (as well as the French rule of short s before 'h') developed in the first place, I suspect that it goes back to blackletter usage, but that is something for future investigation (all I can say at present is that Caxton's Chaucer (1476, 1483) seems to use long s before the letters 'f', 'b' and 'k'). It is perhaps significant that the letters 'b', 'k' and 'h' all have the same initial vertical stroke, but quite what the significance of this is I am not sure.

Short S before H

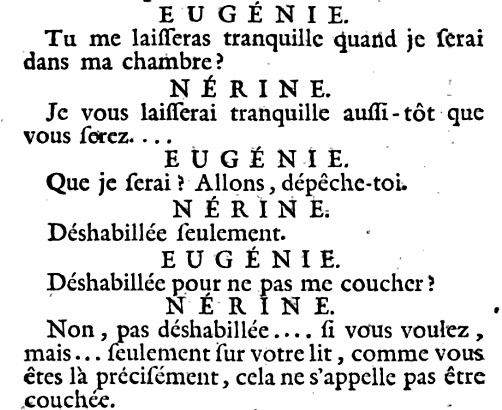

L'Enfant Indocile (London & Paris, 1779) p.106

Short s before h: déshabillée

French and English typographic practice differs in one important respect : French (and also Spanish) typography uses a short s before the letter 'h', whereas English typography uses a long s.

For example, Google Book Search finds 86 books with déshabiller or its various grammatical forms (déshabillé, déshabillée, déshabille, déshabilles, déshabillez or déshabillent) during the period 1700–1799, but only a single book that uses long s : déſhabillé occurs three times in Appel a l'impartiale postérité, par la citoyenne Roland (Paris, 1795).

On the other hand, for the period 1640–1799 Google Books finds 54 books with dishonour and 196 books with diſhonour, but closer inspection shows that almost every single example of dishonour in pre-1790 books is in fact diſhonour or DISHONOUR in the actual text. Similar results were obtained when comparing the occurences of worship and worſhip. Thus it seems that short s was not used before the letter 'h' in English typography.

Short ST Ligature after G

According to John Smith's The Printer's Grammar, first published in 1755, there is a particular rule for italic text only that a short st-ligature is used after the letter 'g' in place of a long st-ligature :

In the mean time, and as I have before declared ;

Italic diſcovers a particular delicacy, and ſhews a ma-

thematical judgement in the Letter-cutter, to keep the

Slopings of that tender-faced Letter within ſuch de-

grees as are required for each Body, and as do not de-

triment its individuals. But this precaution is not

always uſed; for we may obſerve that in ſome Italics

the lower-caſe g will not admit another g to ſtand

after it, without putting a Hair-ſpace between them,

to prevent their preſſing againſt each other : neither

will it give way to ſ and the ligature ſt ; and therefore

a round st is caſt to ſome Italic Founts, to be uſed

after the letter g ; but where the round st is wanting

an st in two pieces might be uſed without diſcredit to

the work, rather than to ſuffer the long ſt to cauſe a

gap between the g and the ſaid ligature.The Printer's Grammar (London, 1787) pages 23-24.

However, I have thusfar been unable to find any examples of this rule in practice. For example, Google Book Search finds several examples of Kingſton in italic type, but no examples of Kingston in books that use a long s :

- An Universal, Historical, Geographical, Chronological and Poetical Dictionary (London, 1703)

- Athenae Britannicae, or, A Critical History of the Oxford and Cambrige Writers and Writings (London, 1716) page 322

- The History of England (London, 1722) page 78

- Scanderbeg: Or, Love and Liberty (London, 1747) page 92

- An Introduction to the Italian Language (London, 1778) page 109

- A Collection of Treaties (London, 1790) page 288

Rules for Long S in some late 18th and early 19th century books

Prior to the complete abandonment of long s in English typography around the turn of the 19th century, there was a short-lived attempt to reform typographic practice to reflect actual usage in contemporary handwriting. Throughout the 18th century, in handwritten English letters and documents, long s was only regularly used in words spelled with a double s medially or finally, in which cases long s was followed by short s (e.g. poſseſs). This was in contrast with normal typographic rules which used long s for both letters in the middle of a word (e.g. poſſeſs). During the 1790s and early 1800s (circa 1792–1805) some publishers in England and Scotland produced books that adhered to the simplified rules for long s used in handwriting.

The rise of the handwriting rules for long s can be seen in The Bee, or Literary Weekly Intelligencer edited and published in Edinburgh by James Anderson between 1791 and 1793. Volumes 1–6 use the normal late 18th century rules for long s, whereas volumes 7–18 use long s before short s medially and finally, and elsewhere only before b, h and k (usage of long s before b and k is erratic, but long s is always used before h).

The Bee vol.6 (Edinburgh, 1791) p.125

Vols. 1-6 (1791): normal typographic long s rules

The Bee vol.7 (Edinburgh, 1792) p.77

Vols. 7-18 (1792–1793): long s before s, b, h and k: tenderneſs, aſsiduity, distinguiſhed, ſhe, ſhewn, laviſh, huſband, taſk of bloodſhed (p.270)

The Bee is the only publication that I have been able to find that used long s before b, h and k as well as before short s, although some other books written and published by James Anderson used long s before h as well as before short s (e.g. General View of the Agriculture and Rural Economy of the County of Aberdeen (Edinburgh, 1794)). Other books published in England and Scotland during the last decade of the 18th century and the first decade of the 19th century that used the handwriting rule for long s did so exclusively, with long s not normally used in any other position (although in some books long s or long s ligatures did occasionally slip in in unexpected places).

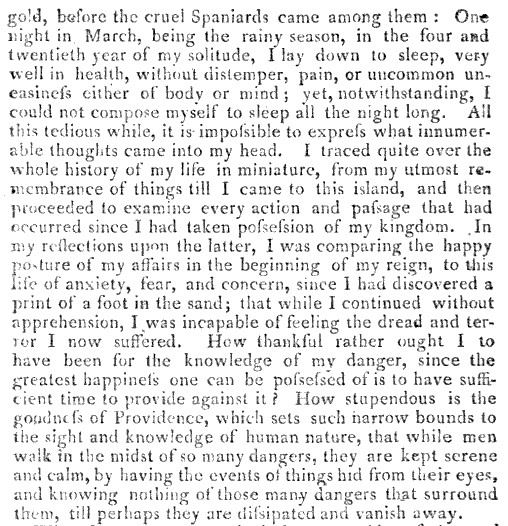

These handwriting-based rules for long s were only used by a relatively small number of publishers for a short period of time, and by the middle of the first decade of the 1800s these rules had been discarded in favour of not using long s at all in most publications, as discussed below. About the latest publication that I have found that only uses long s only before short s (although not throughout the entire book) is an edition of Robinson Crusoe published in London in 1805.

The Life and most Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (London, 1805) p.82

uneasineſs, impoſsible, expreſs, paſsage, poſseſsion, happineſs, poſseſsed, goodneſs, diſsipated

The Demise of the Long S

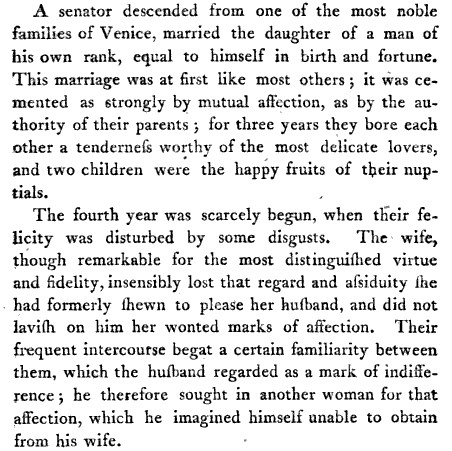

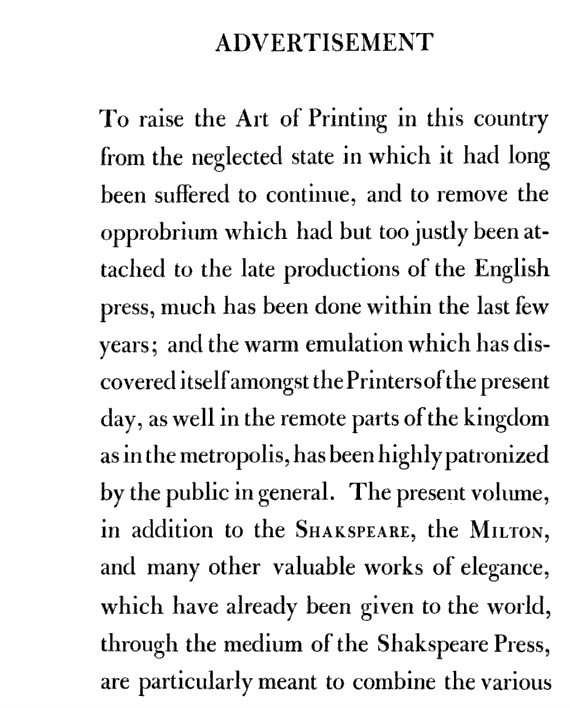

Long s was used in the vast majority of books published in English during the 17th and 18th centuries, but suddenly and dramatically falls out of fashion at the end of the 18th century, reflecting the widespread adoption of new, modern typefaces based on those developed by Bodini and Didot during the 1790s. In England this movement was spearheaded by the printer William Bulmer, who set the benchmark for the new typographical style with his 1791 edition of The Dramatic Works of Shakspeare, printed using a typeface cut by William Martin. The ſ-free typeface used by Bulmer can be seen in this Advertisement to his 1795 edition of Poems by Goldsmith and Parnell :

Although throughout most of the 1790s the vast majority of English books continued to use long s, during the last two or three years of the century books printed using modern typefaces started to become widespread, and in 1801 short s books overtook long s books. The rise of short s and decline of long s, as measured by the occurences of the word those compared with thoſe in Google Book Search, is charted below.

| Date | those | thoſe |

|---|---|---|

| 1780 | 2 | 140 |

| 1781 | 0 | 114 |

| 1782 | 0 | 112 |

| 1783 | 0 | 98 |

| 1784 | 3 | 131 |

| 1785 | 3 | 85 |

| 1786 | 5 | 132 |

| 1787 | 4 | 167 |

| 1788 | 4 | 174 |

| 1789 | 2 | 131 |

| 1790 | 7 | 191 |

| 1791 | 3 | 141 |

| 1792 | 9 | 192 |

| 1793 | 38 | 206 |

| 1794 | 46 | 292 |

| 1795 | 16 | 251 |

| 1796 | 44 | 199 |

| 1797 | 62 | 165 |

| 1798 | 57 | 152 |

| 1799 | 105 | 151 |

| 1800 | 108 | 224 |

| 1801 | 198 | 181 |

| 1802 | 210 | 202 |

| 1803 | 240 | 164 |

| 1804 | 336 | 118 |

| 1805 | 294 | 151 |

| 1806 | 328 | 130 |

| 1807 | 361 | 136 |

| 1808 | 418 | 54 |

| 1809 | 406 | 74 |

| 1810 | 492 | 66 |

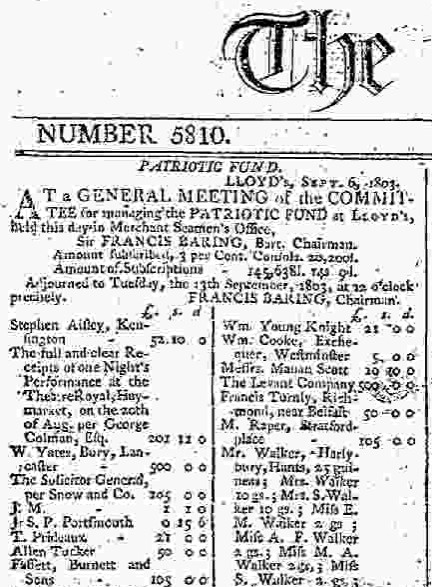

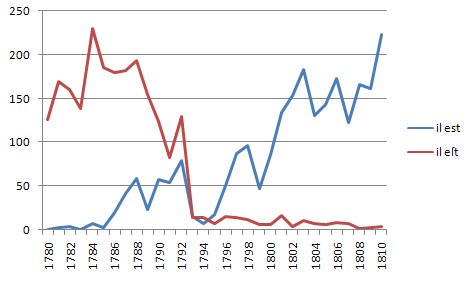

The death knell for long s was finally sounded on September 10th 1803 when, with no announcement or any of the fuss that accompanied the typographic reform of October 3rd 1932 (see the articles in the issues of Sept. 26th and 27th 1932), The Times newspaper quietly switched to a modern typeface with no long s or old-fashioned ligatures (this was one of several reforms instituted by John Walter the Second, who became joint proprietor and exclusive manager of The Times at the beginning of 1803).

The Times Issues 5810 & 5811 (September 9th and 10th 1803)

(compare the words ſubſcribed/subscribed and Tueſday/Tuesday in the first paragraph)

After the end of the first decade of the 19th century very few books continued to use long s in any shape or form, and those that did were often reprints of earlier editions that had been typeset before long s went out of fashion. Perhaps the last major publication to be printed using long s was the 5th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica (Edinburgh, 1817), its anachronous use of normal long s rules being due to the fact that it was a reprint with a some corrections of the 4th edition that had been published in 1810 (the 6th edition, published in 1823, was the first to be typeset in a modern font with no long s).

By the second half of the 19th century long s had entirely died out, except for the occasional deliberate antiquarian usage (for example, my 1894 edition of Coridon's Song and Other Verses uses long s exclusively before short s in words such as poſseſs).

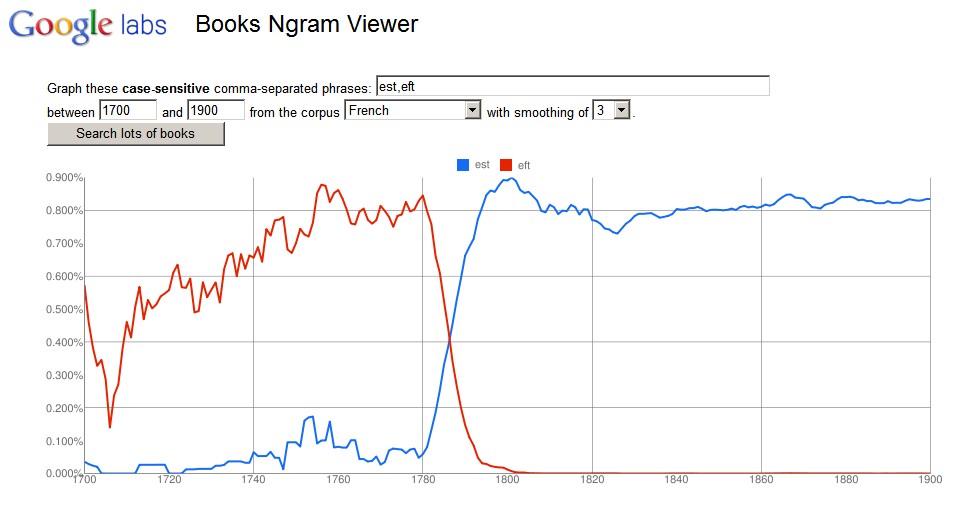

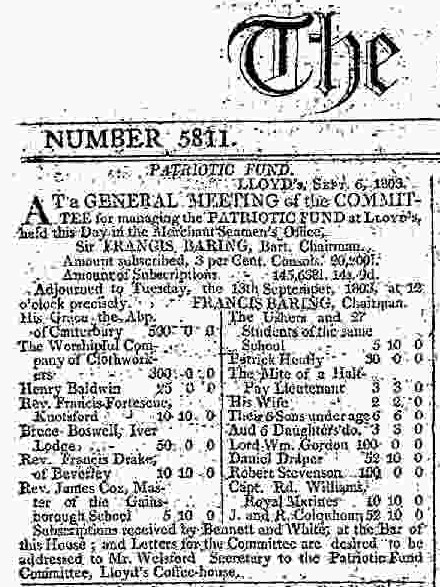

As might be expected, the demise of long s in France seems to have occured a little earlier than in England. Based on the following Google Book Search data for il est and il eſt, it seems that short s started to gain popularity from the mid 1780s, and long s had been almost completely displaced by 1793 (many of the post-1792 examples of long s are from books published outside France).

| Date | il est | il eſt |

|---|---|---|

| 1780 | 1 | 126 |

| 1781 | 3 | 170 |

| 1782 | 4 | 161 |

| 1783 | 1 | 139 |

| 1784 | 8 | 230 |

| 1785 | 3 | 185 |

| 1786 | 20 | 180 |

| 1787 | 42 | 182 |

| 1788 | 59 | 194 |

| 1789 | 24 | 155 |

| 1790 | 58 | 124 |

| 1791 | 55 | 83 |

| 1792 | 80 | 130 |

| 1793 | 16 | 14 |

| 1794 | 8 | 14 |

| 1795 | 18 | 8 |

| 1796 | 51 | 16 |

| 1797 | 88 | 15 |

| 1798 | 97 | 12 |

| 1799 | 48 | 7 |

| 1800 | 86 | 6 |

| 1801 | 134 | 17 |

| 1802 | 154 | 4 |

| 1803 | 183 | 11 |

| 1804 | 131 | 8 |

| 1805 | 143 | 6 |

| 1806 | 173 | 9 |

| 1807 | 123 | 8 |

| 1808 | 166 | 2 |

| 1809 | 162 | 3 |

| 1810 | 223 | 4 |

Note on Methodology

The statistics given here are based on the results returned from searches of Google Book Search (filtering on the appropriate language and "Full view only"), which allows me to distinguish between words with long s and words with short s only because the OCR software used by Google Book Search normally recognises long s as the letter 'f', and so, for example, I can find instances of huſband by searching for 'hufband'. However, for a number of reasons the results obtained are not 100% accurate.

Firstly, the search engine does not allow case-sensitive searches, so whereas searching for 'hufband' only matches instances of huſband, searching for 'husband' matches instances of both husband and HUSBAND, which skews the results in favour of short s.

Secondly, hyphenated words at a line break may match with the corresponding unhyphenated word, so searching for 'hufband' may match instances of 'huſ-band', which is not relevant as long s is expected before a hyphen (Google Book Search shows 583 matches for 'huf-band', but only 3 for 'hus-band' for the period 1700–1799).

Thirdly, long s is sometimes recognised by the OCR software as a short s, especially when typeset in italics.

Fourthly, the publication date given by Google Book Search for some books is wrong (for various reasons which I need not go into here), which I often found was the explanation for an isolated unexpected result.

Fifthly, when Google Book Search returns more than a page's worth of results, the number of results may go down significantly by the time you get to the last page.

Finally, and to me this is most perplexing, Google Book Search searches in March 2008 gave me over twice as many matches than in May 2008 using the same search criteria, so, for example, I got 438 matches for 'husband' and 956 matches for 'hufband' for the period 1790–1799 in March, but only 187 and 441 matches respectively for the same search when redone in May (nevertheless, the figures for March and May showed exactly the same trends for husband versus huſband). For consistency, the figures shown for 'husband/hufband' and 'ask/afk' are those that I obtained in May 2008 (I may try redoing this experiment in a year's time—providing Google Book Search does not improve its OCR software to recognise long s in pre-19th century books—and see if the trends for husband versus huſband and ask versus aſk are roughly the same or not).

And Finally...

If you have managed to get this far, you may well be interested in my brief, illustrated history of the long s (The Long and the Short of the Letter S), which to most people's surprise starts in Roman times.

And if the rules of long s are not enough for you, try out my Rules for R Rotunda (a post that I think needs some revision when I have the time).

Addendum [2010-12-17]

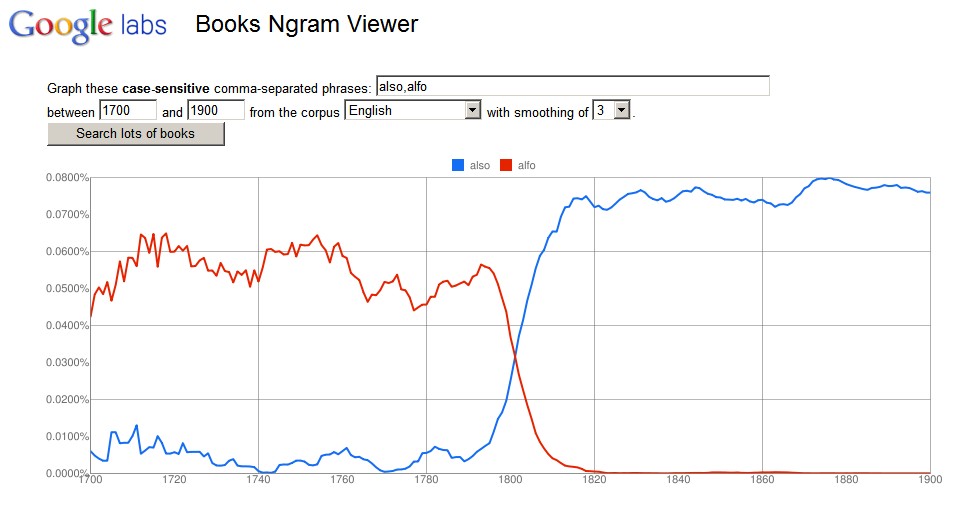

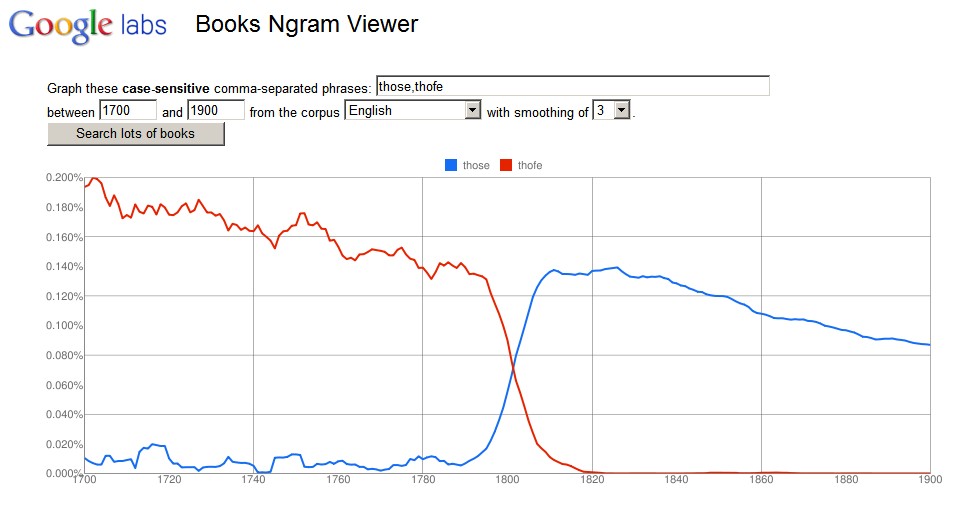

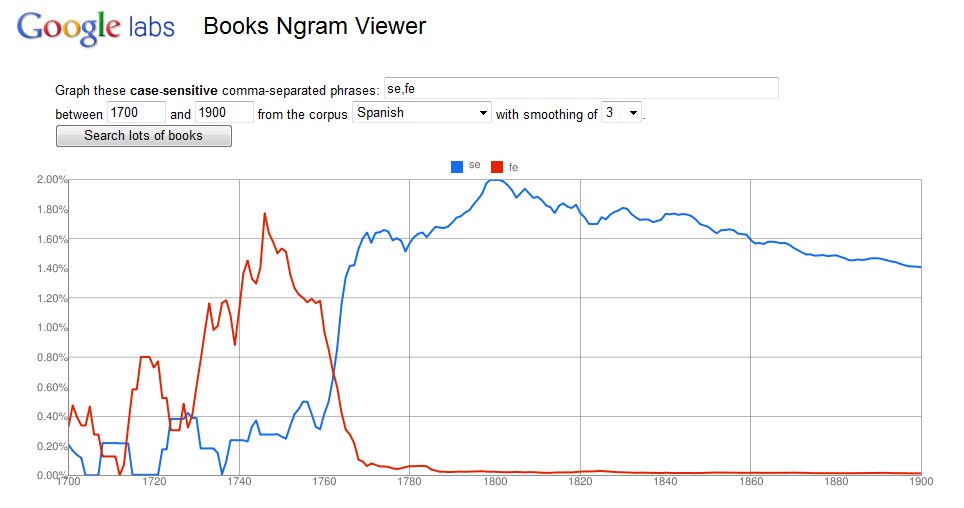

Google have now released the Books Ngram Viewer which allows you to plot the relative frequency of up to five words (or n-grams) over a given period of time. The following are the results for some of the words discussed above, which tend to confirm my original findings.

N-gram plot for "ask" vs. "afk" ("aſk") in English, 1700–1900

This shows that long s was not widely used before the letter k in English before about 1740

N-gram plot for "husband" vs. "hufband" ("huſband") in English, 1700–1900

This shows that long s was not widely used before the letter b in English before about 1740

N-gram plot for "also" vs. "alfo" ("alſo") in English, 1700–1900

This shows that long s went out of use in English about 1800

N-gram plot for "those" vs. "thofe" ("thoſe") in English, 1700–1900

This shows that long s went out of use in English about 1800

N-gram plot for "est" vs. "eſt" ("eſt") in French, 1700–1900

This shows that long s suddenly started to go out of use in French in 1780

N-gram plot for "se" vs. "fe" ("ſe") in Spanish, 1700–1900

This seems to show that long s went out of use in Spanish about 1760

[As of 2013, Google Ngram Viewer no longer supports searches for words with long s using 'f', as long s is normalized to short s by Google's OCR software in most cases. Searching using an actual long s also fails as the long s is converted to short s before the search operation is processed (you get a message such as "Replaced huſband with husband to match how we processed the books"). However, you can still use the 'f' hack for long s in ordinary Google Books search.]

First published: 2006-06-12

Revised and extended: 2008-05-26

Rules for French added: 2008-06-05

Rules for Spanish added: 2008-06-09

Rules for Italian added: 2008-06-12

Google Ngrams added: 2010-12-17

Last revised: 2013-01-30

A version of this post, edited by Werner Lemberg, was published in TUGboat (The Communications of the TeX Users Group) as Andrew West, The rules for long s, TUGboat Volume 32, Number 1, 2011 (TUGboat #100) pages 47–55.

Index of BabelStone Blog Posts