BabelStone Blog

Sunday, 23 July 2006

R Rotunda Part 1

Having recently discussed long s (in some detail), I want to turn my attention to r rotunda, in the second of a series of posts related directly or indirectly to the Proposal to add medievalist characters to the UCS (N3027) co-authored by Michael Everson and members of the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI). This is a very important proposal to encode many letters and abbreviations used in medieval manuscripts or used by scholars of medieval manuscripts. I very much support the encoding of characters which will finally allow textual scholars and pedants such as myself to faithfully reproduce the contents of medieval manuscripts and early printed books in electronic text format; although, as some of my readers already know, I do have concerns over some of the characters proposed in N3027.

The Origins of R Rotunda

R rotunda is a '2'-shaped variant form of the lowercase letter 'r' used in medieval manuscripts and early printed books. Like the long-s, r rotunda only occurs in lower case, but whereas long-s is normally used initially and medially within a word but not finally, r rotunda is used medially and finally in a word after certain letters but never initially. Furthermore, r rotunda is normally only used in blackletter styles of typeface (or Gothic styles of mansuscript). Therefore, when roman typefaces replaced blackletter for printing during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, r rotunda disappeared from the scene. As far as I can tell, in recent centuries, German books set in Fraktur do not use r rotunda.

R rotunda apparently developed from a ligature of the letters O and R (minuscule 'r' being written as 'R' in half uncial scripts) where the lefthand stroke of the 'R' merged with the 'O'. I'm not sure exactly when or where this happened, although I'm told that r rotunda is first seen in the southern Italian Beneventan script that developed during the 8th century. You can certainly see r rotunda and its cousin rum rotunda (r rotunda with a stroke, used as an abbreviation for Latin -rum) in British Library MS Burney 284, but this is comparatively late in date (late 11th to early 12th century) and so not particularly significant. Unfortunately, I have found it hard to find any examples of early Beneventan manuscripts, so I can't really confirm or deny the theory that r rotunda originated in the Beneventan script.

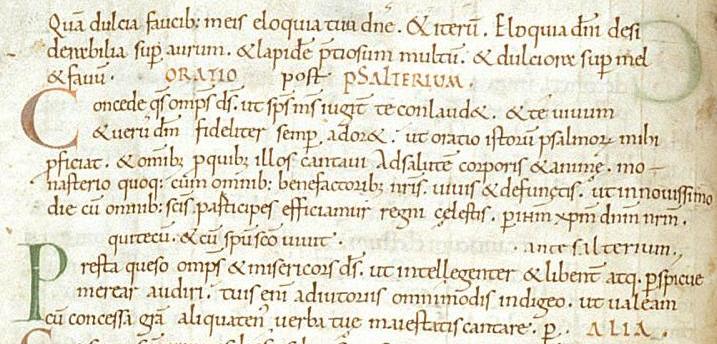

Whatever their origins, r rotunda and rum rotunda can be seen in some late 10th and early 11th century manuscripts written in the Carolingian script, such as British Library MSS Cotton Cleopatra C. VIII (late 10th century) and Arundel 375 (late 10th or early 11th century). The example below is from a manuscript written by the scribe Eadui Basan at Canterbury between 1012 and 1023 :

Eadui Psalter (British Library MS Arundel 155 folio 11v)

"adoret" (line 5), "iſtorum" (line 5), "pſalmorum" (line 5), etc.

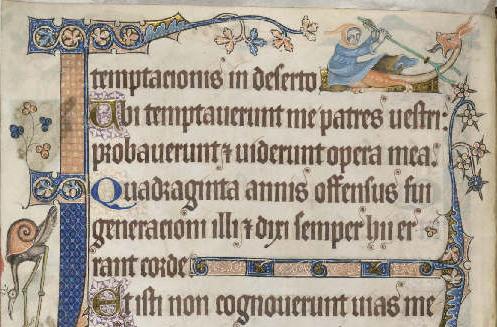

When the Gothic script came to replace the Carolingian script in the 12th century, it inherited the r rotunda form of the letter 'r' after the letter 'o'. At this stage, the r rotunda is still joined to the preceding letter, and may still be considered to be a ligature of the two letters, but by the end of the medieval period the ligature had become broken, and r rotunda became perceived as a separate form of the letter 'r', in the same way that long-s was perceived as distinct form of the letter 's'. Although initially restricted in position to following the letter 'o', r rotunda soon came to be used after any letter that (in Gothic script) ended with a rounded stroke, as can be seen in this page from the Luttrell Psalter (circa 1325-1335) :

Luttrell Psalter folio 171v

"probauerunt" (line 3), "Quadraginta" (line 4), "corde" (line 6).

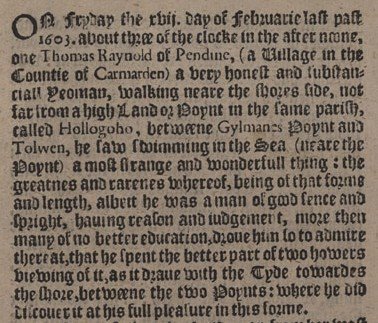

Early printed books retained all the peculiar letters and abbreviations used in mansuscripts, including r rotunda, which can be seen (in various glyph forms) in books set in blackletter typefaces up until the early 17th century :

A most strange and true report of a monsterous fish page A3 (London, 1604)

"februarie" (line 1), "three" (line 2), "ſhores" (line 5), "ſpright" (line 12), "droue" (line 13), etc.

The Rules of R Rotunda

In order to try to come to an understanding of the rules for using r rotunda in printed books, I have roughly analysed the usage of r rotunda in a small selection of books written in various languages that were printed in blackletter type between the mid 15th and early 17th centuries. The results are tabulated below. With hindsight I should have noted for each book which letters ordinary 'r' follows as well as which letters r rotunda follows, otherwise it is not obvious whether a letter is not listed as preceding r rotunda for a particular book because the letter only precedes an ordinary 'r' or because there are no examples of any sort of 'r' following that letter in the book. Although I do not have the time or energy to go back and repair this omission at the present time, in a few cases I have explicitly indicated that a particular letter is not followed by r rotunda by enclosing it in square brackets (thus [y] for The Canterbury Tales means that 'y' is followed by ordinary 'r'). An asterisk is used to indicate cases where a particular letter is mostly followed by ordinary 'r', but occasionally by r rotunda. Single anomalous occurences of r rotunda where ordinary 'r' would be exepected or ordinary 'r' where r rotunda would be expected are generally ignored.

† Actually printed secretly in a cave on the estate of Robert Pue of Penrhyn Creuddyn during 1586 and 1587.

The following is a summary of my findings :

- There is a core set of letters with a final rounded stroke (B, D, O, P, V, W, b, h, o, p, v, w) after which r rotunda is almost always used, regardless of place or date of publication.

- The letter 'd' is normally followed by r rotunda when it has a bent back, but not if it has a straight back.

- The letter 'y' mostly takes r rotunda, but not in all books.

- The only letter that consistently takes r rotunda where ordinary 'r' would normally be expected is the letter 'r' in the Schönsperger Bible, where der herr "the Lord" (and inflexions) is written with an ordinary 'r' followed by r rotunda (see picture in rules for long s).

- An apostrophe can intervene between r rotunda and a preceding letter, thus Welsh o'r is written with r rotunda.

What is also striking is that in almost every book examined the rules of r rotunda are not applied uniformly, and there are cases where ordinary 'r' is found after a rounded letter such as 'o', as well as cases where r rotunda is found after letters such as 'a' or 'i' that should be followed by ordinary 'r'.

Y Drych Cristianogawl is an extreme example of eratic usage of r rotunda. It starts off with fairly well-defined rules, but about half way through the book we start to see r rotunda popping up after all sorts of letters that should not take r rotunda -- presumably one of the hazards of printing illegal Catholic tracts secretly in a cave (other than being burnt at the stake) is that you may have to rely on unskilled typesetters.

In the case of capital 'G', it is not at all clear which form of letter 'r' it should be followed by, as almost all the books which have examples of G plus r rotunda also have counter examples showing G plus ordinary 'r'.

Thus, it seems to me, the rules for r rotunda are less well defined and less strictly enforced than the rules for long s.

More on r rotunda tomorrow.

Addendum I [2008-04-04]

R rotunda, in both its normal, lowercase form and the abnormal uppercase form, has now been encoded in Unicode 5.1 :

- U+A75A Ꝛ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER R ROTUNDA

- U+A75B ꝛ LATIN SMALL LETTER R ROTUNDA

The Unicode case mappings mean that if you uppercase U+A75B ꝛ LATIN SMALL LETTER R ROTUNDA you will get U+A75A Ꝛ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER R ROTUNDA (a virtually non-existant letter) rather than the expected ordinary uppercase letter R. In my opinion, this is an abomination of the same order as it would be to have long s uppercase to an artificial capital long s,

Addendum II [2008-06-21]

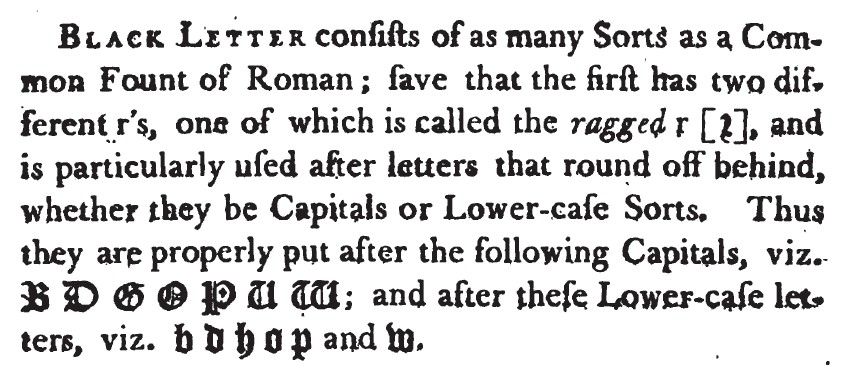

I have now discovered that the rules for r rotunda (ragged r as he calls it) or are laid out in John Smith's Printer's Grammar, first published in 1755 :

Black Letter conſiſts of as many Sorts as a Com-

mon Fount of Roman ; ſave that the firſt has two dif-

derent r's, one of which is called the ragged r [ꝛ], and

is particularly uſed after letters that round off behind,

whether they be Capitals or Lower-caſe Sorts. Thus

they are properly put after the following Capitals, viz.

B D G O P U W ; and after theſe Lower-caſe let-

ters, viz. b d h o p and w.The ragged r, of which we have taken this ſhort

notice, witneſſeth, that the German letters owe their

being to the Gothic or Black characters that were firſt

uſed for Printing : for the Germans have a ragged r,

which they call the round r ; but which, in modelizing

their letters to the preſent ſhape, they have castrated, by

depriving it of its comely tail. But that they do not

know the proper application of that letter, may be ga-

thered from their uſing it in very cloſe lines, inſtead of

common r's, thereby to gain the room of a thin Hair-

ſpace. Which obſervation we have made on purpoſe

to aſſiſt thoſe who delight to exercise themſelves in that

painful ſtudy which attends writing De Origine rerum.The Printer's Grammar (London, 1787) page 112.

The rules stated by Smith accord fairly well with my empirical observations, with the exception that the letter y is also usually followed by r rotunda.

Index of BabelStone Blog Posts